“What was I doing!?” I shrieked, shielding my face with my hands. I was flipping through old photo albums with my mom and stumbled upon a particularly embarrassing photo of my preteen self.

“What was I doing!?” I shrieked, shielding my face with my hands. I was flipping through old photo albums with my mom and stumbled upon a particularly embarrassing photo of my preteen self.

In the photo, I was wearing a sweatshirt that said Genuine Girl, only I put masking tape over Girl and wrote Alien in black marker. Genuine Alien. I wore this to a Mardi Gras themed fundraiser at my middle school. I was also wearing butterfly face paint.

Of course, I knew what I was doing in the picture. I didn’t have to ask. It was the time in my life when I was obsessed with aliens. Not pictured were my little alien dolls, each with full life stories of my own invention. I was a strange child.

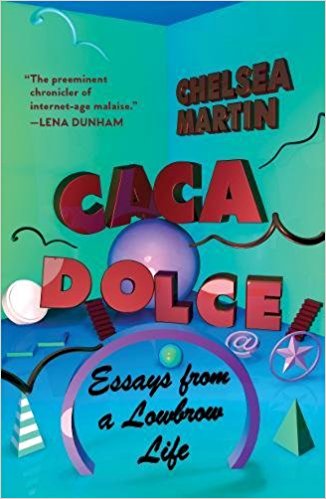

I thought of that picture while reading Chelsea Martin’s recent collection of essays, Caca Dolce: Essays from a Lowbrow Life. The collection contains the essential stories of her childhood into young adulthood, in which she describes her younger self as a delightful concoction of strangeness. In one essay, “The Meaning of Life,” Martin reveals how she too was preoccupied by aliens. She describes her attempts to summon aliens, believing they had special knowledge far beyond human understanding. She hoped they would reward her belief in their existence and share secrets with her, most importantly the meaning of life.

The strangeness of a child normally doesn’t make sense to anyone else, but Martin finds a way to present her childhood curiosities logically and with deadpan delivery. She is honest and self-deprecating while maintaining a certain aloofness to her humor that keeps readers unflinchingly by her side. Better still, she captures not only the absurdities of the young mind but also the discomfort. A large part of growing up is the discomfort of an evolving mind, a mind which eventually recognizes former childhood notions for what they are. In the essay, “A Year Without Spoons,” Martin describes choosing to give up spoons for seemingly no reason at all, even though a part of her realizes this is an unusual choice:

I stopped using spoons one day. I was becoming weird, I knew. And it didn’t seem like the good kind of weird, like the eccentric arty weird that could be appreciated by other people. It seemed like the bad, dark kind that could unravel a person if it got out of hand.

Many of Martin’s essays unfold to reveal more tender and complex undertones. The spoons, for example, become a coping mechanism for the lack of control Martin had over her life during a time when she switched schools a lot and had no real friends. Her choice of utensil became a way to practice control and restraint and, in a way, it felt like an achievement.

Some of the many topics of Martin’s “Lowbrow Life” include her sheltered small town, troubled relationship with her stepfather, living with mild Tourette’s syndrome or OCD, meeting her biological father for the first time, attending art school, and various romantic endeavors. Martin often manages to capture the essence of her quirky former selves in just a few words. As I breezed through the pages, I was often left thinking, how did she do that?

In the essay, “Ceramic Busts,” we observe teen-Martin’s attempts at flirting with a boy named Sandy at driving school:

“My favorite Beck song is ‘Thunder Peel,’” I said. ‘The one that’s like, Now I’m rolling in sweat with a loaf of cold bread and a taco in my jeans.

I had practiced the lyrics over the weekend, perfecting my falsetto delivery. I’d hoped that it would make him smile.

“Oh,” Sandy said.

I giggled.

After finishing driving school and leaving that town behind, having had no meaningful interactions with Sandy, Martin goes on to create many artistic renderings of him, mostly ceramic busts. She eventually submits these for her application to art school and gets accepted.

In an essay titled, “Goth Ryan,” Martin attempts to communicate through facial expression:

Before he disappeared, I tried to give him a look that said I don’t care what you do, and Like at all, and Anyway Zach is here and we are in love, we are going to tell each other how in love we are and soon you will be merely a distant foggy memory that rarely occurs to me, and when I’m older I will conflate you with someone else I knew around this time and you will become a half-person, so unimportant on your own that I couldn’t be bothered to remember you as one being, so utterly useless in my memory that you barely exist, and But in all seriousness, I really don’t care.

Martin’s subject matter becomes more serious towards the middle of the book as she describes meeting her father for the first time at age sixteen, which she says is “an age that is known for being awkward and unbearable and confusing.” It’s already clear to readers that Martin has a difficult relationship with her stepfather, Seth, and it’s apparent early on that Martin’s relationship with her father will also be flawed to say the least. Martin strikes the perfect balance between funny and fraught while talking about her father’s relentless disapproval of her. He criticized her for everything from how much sour cream she eats with dinner to her acne.

I tried to understand what the problem was. My dad wanted to change what I did and said, and also the ways in which I did and said them, implying that possibly everything about me was, if not outright wrong, somehow off, in need of correction.

As writers, we are naturally wondering about the potential repercussions that can come from writing about people we know, especially those related to us. This, Martin addresses in her final essay, “The Man Who Famously Inspired This Essay,” in which she expresses her decision to take a break from her relationship with her dad and eventually choosing to write about him:

“You’re going to thank me one day for giving you all this material for your writing,” [My dad] said when I stopped crying.

I avoided eye contact and silently promised to never write a damned thing about him.

I love the irony here, how Martin writes about never writing about her father. She concludes the essay, and thus her collection, with: “And though I’m comforted by the fact that this past self seemed to know that it was always her story to tell or not tell, I have to admit that what she didn’t yet know is I never keep promises to myself.” I can’t help but think that this was Martin’s pre-emptive response to our pressing question: it was always her story.

Although I love Martin’s detailing of her poorer, less cultured hometown and lifestyle, this collection gives us more than simply “Essays from a Lowbrow Life,” as the subtitle suggests. These essays are also about the common rites of passage that face most of today’s young people. This book is about leaving home and coming to terms with flawed relationships. It’s about being friendless and making weird fashion choices. It’s about learning to bullshit. It’s about becoming be self-reliant and making countless mistakes along the way.

Like looking at childhood photos, this book is as uncomfortable as it is humorous. It reads like a memory we might have been a part of in another life and reminds us of our shared humanity through even the most painful times of self-discovery.

___

Lizzie Klaesges is a Minneapolis-based writer and marketer with recent publications in Rain Taxi, The Critical Flame, and Allegory Ridge. She definitely does not still think about aliens.