I came across some of my deceased father’s clothing while getting ready to move last month: a Hawaiian shirt I bought him when I visited Oahu and some old military fatigues.

I came across some of my deceased father’s clothing while getting ready to move last month: a Hawaiian shirt I bought him when I visited Oahu and some old military fatigues.

When I was going through his house after he died, about a decade ago, these clothes seemed the perfect objects to hold onto. I could wear them and feel like he was hugging me, or remember what he looked like, or maybe just smell the collars and hope his scent still lingered. But the clothing has sat unworn all this time. I looked at the small stack a long while, trying to decide what to do: keep or discard? The clothes don’t hold his smell anymore, just the scent of dust. I have other, more practical and meaningful things: pictures, pens, jewelry, blankets. But how can I throw anything away when things are all I have left of him?

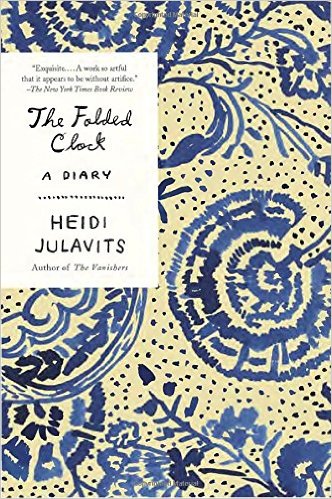

In an honest, clever, sincere voice, Heidi Julavits examines a similar conundrum in The Folded Clock: A Diary, which made the New York Times Notable Book list. For Julavits, it isn’t clothing of a loved one but rather a tap handle found inside the walls of her house. She is drawn to this tap handle, finds beauty, mystery, and creativity in it, so much so, she carries it in her purse and begins her days drawing it. She thinks about the tap handle and other objects that take on intriguing importance in our lives and writes, “I, too, have been frustrated by objects that you cannot file anywhere in your life, but neither can you throw them away. They drift around a house transiently, in a death row limbo, first on the dining room table, then on a bookshelf.” She understood my experience. I felt acknowledgement, camaraderie.

I felt this also after reading her entries about being a working mother, writer, and human being, particularly those that addressed some of my own fears: “my child will be older and I will be nearer to dead.” I understood as well, “I often have a pen in my hand when I read. I am trying to fool myself into thinking I am writing when I’m not.”

This collection of entries is thoughtful and deliberate. Julavits goes beyond using the diary as a way to record daily events. She might begin this way, but questions herself and society, trying to understand larger ideas. Julavits compresses and flings time wide as she jumps around these two years. At one point she moves from January 3 to November 4 to August 4 and then back to January. I mapped out the dates to see if there was a pattern, a hidden meaning to what seemed like randomness. I couldn’t figure it out. I wondered if I was missing something. But maybe the timeline is supposed to be haphazard.

Julavits begins the collection with a beautiful exploration of time, asking, “What is the worth of a day? Once a day was long…. Rages flared and were forgotten and replaced by new rages, also forgotten. Within a day there were discernible hours, and clocks with hands that ticked out each new minute.” But then she goes on to confide that time doesn’t exist like that for her anymore—that it has folded in on itself and “the ‘day’ no longer exists.” I can’t help but see this diary as a way for Julavits to take time back into her own hands, unfold it and see what a single day can hold.

For me, the days in this collection hold a voice that is lively and nuanced with quick, provocative asides and poignant contemplations. Again, when thinking about the tap handle, Julavits writes, “When I am autopsied they will find inside—this tap handle, a child too scared to go to matinees, a song I once loved, maybe also a cow bone and some old news. Who knows what else I’ve hidden in there because I could make no sense of it at the time, and found nowhere else to put it.” That seems like the perfect place to put my father’s clothes—not folded on the closet shelf, but “stored between the studs of the walls of [my] self.”

___

Courtney Ruttenbur Bulsiewicz recently completed her MFA at Brigham Young University, where she currently teaches writing as an adjunct professor. Her work has been publishedi n Inscape and Con*text.

1 comment

Tinaka Durden says:

Oct 29, 2016

This is amazing. I am new to writing and I only hope that one day I too can write with such detail and creativeness. I really liked this!