I have a friend named Rachel, who is a Holocaust survivor. Rachel is a short woman, with loosely curled hair, faded to white. Her eyes are brown, and the skin of her cheeks is soft when she kisses me hello. A scent of baby powder always lingers around her.

I have a friend named Rachel, who is a Holocaust survivor. Rachel is a short woman, with loosely curled hair, faded to white. Her eyes are brown, and the skin of her cheeks is soft when she kisses me hello. A scent of baby powder always lingers around her.

Rachel and I have talked many times about the story of her life. Born in 1927 in Belgium to a Jewish family, she was hidden during the war at a convent by a group of nuns. Rachel described to me the ever-present fear she felt of being discovered. But Rachel survived the war.

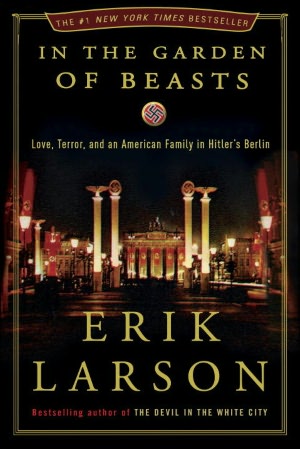

In learning about Rachel’s experience, one question about the Holocaust has endured most for me: “how could it have happened?” Such a question lays at the heart of Erik Larson’s book In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin. In its introduction, Larson explains that he always wondered what it had been like at the dawn of Hitler’s regime. “Hindsight tells us that during that fragile time the course of history could so easily have been changed,” he writes. “Why, then, did no one change it?”

The answer, Larson discovers, is that few were able—or willing—to fully recognize the threat Hitler posed. Larson demonstrates this by chronicling the experiences of the Dodd family. In July 1933, William Dodd arrived in Berlin as America’s new ambassador to Germany. His wife, son, and free-spirited daughter, Martha, accompanied him. Larson follows the family’s first year in Germany, a critical time that also “coincided with Hitler’s ascent from chancellor to absolute tyrant,” as Larson writes.

The Dodds did not initially recognize Hitler’s threat themselves, because they were enamored of his new Germany. Dodd, a history professor, actually had no diplomatic experience, though he had a deep appreciation for German culture. His first opinion was that Hitler’s government was becoming more moderate. His daughter, Martha, was an aspiring writer and a romantic. She soon engaged in multiple affairs, including ones with a German flying ace, a Russian spy, and even a head of the Gestapo.

Yet as time progressed, attacks on Jews, on the Nazis’s political opponents, and even on American citizens, increased. At last, nearly a year after the Dodd’s arrival in Berlin, the city exploded in an episode of public, government-sanctioned mass murder, all at the merest whim of Hitler. It finally left the Dodds repulsed by Hiter’s regime and frightened. But when Dodd tried to sound the alarm with America’s State Department, he was met with disbelief, condescension and resistance. To those back home in an increasingly isolationist America, the reports from Germany seemed histrionic.

With Larson’s tight focus on a single year of Hitler’s early rule, with his depictions of characters endearing, yet fallible, and with his vivid descriptions of Berlin, he leaves his reader fully immersed in the world he captures. It is this immersion that best helps us understand how the threat of Hitler went unrecognized. Like the people of that time who did not know what the ultimate consequences of the Nazis would be, so successful is Larson’s writing that we almost forget that we do know what consequences will arise—almost. Here, Larson acknowledges one of the challenges of his genre. “That’s the trouble with nonfiction,” he writes. “One has to put aside what we all know now to be true.”

Yet Larson’s purpose is not for us to forget what we know of the end of Hitler’s power. He knows that the consequences remain ever-present in readers’ minds. My friend Rachel, even though she survived the war, lost both her sister and father at Auschwitz. What Larson achieves so masterfully in this book is a tense juxtaposition between what was known then, and what we know now. It is a juxtaposition wrought as finely as the edge of a knife blade —and as sharply felt.

A.M. Horowitz is a specialist in the Nazis’s confiscation of art during World War II. She also holds an MFA in creative nonfiction writing from Goucher College. She lives in New Jersey.