Every time we praise a literary book for its heft, we contribute to a kind of aesthetic confusion. The sheer length of a text is not a mark of its literary excellence or worth. Rather, it’s a reflection of the material conditions of the author’s life: a mark of the amount of time—free from more urgent obligations—that the writer possessed. When we talk about the length of a work, we need to acknowledge that we are talking about privilege. Not excellence, not talent. Privilege.

Every time we praise a literary book for its heft, we contribute to a kind of aesthetic confusion. The sheer length of a text is not a mark of its literary excellence or worth. Rather, it’s a reflection of the material conditions of the author’s life: a mark of the amount of time—free from more urgent obligations—that the writer possessed. When we talk about the length of a work, we need to acknowledge that we are talking about privilege. Not excellence, not talent. Privilege.

Publishing flash pieces in national journals twenty years ago, I lived below the poverty line. I was raising a child. For maternity leave, I’d been granted two weeks. I had no family nearby. For a while I was single, and for a long while I was putting myself through college and then graduate school. Snatches of time late at night at the kitchen table—after my son was asleep, before I fell asleep, too—were typically the only opportunities I found to write.

My published pieces were correspondingly short. I knew that the traditional benchmarks of literary achievement were well beyond my reach—and would remain so—due to the conditions of my life.

I could not write for hours at a time on the weekend. I could not go to literary colonies and devote myself to writing while someone brought me little lunches in a basket. I would remain a “no-book writer” for years.

Only when I’d earned a sabbatical did I manage to write my first book. Only in my mid-forties, with my son safely raised and through college himself, have I published my second and third. My student loans paid off, I work only one teaching job now, instead of two. I still teach full-time, but I have the luxury to sit and write on weekends and in the summers.

As the conditions of my life have changed, the length of my published texts has grown. These are tremendous privileges.

In the critical assessment of literature, length is still considered a hallmark of virtuosity, and the hoary notion persists that the Great American Novel is a standard of literary achievement. This fact has unfortunate gender and class implications, as short forms—especially flash forms—are particularly amenable to writers snatching time from obligations.

Such writers by definition include family caregivers, who continue to be mostly women, and people from poverty and the working class. Due to the continuing intersection of economic hardship with racial and ethnic minority status in our culture, they also include many writers of color.

The elderly caregiver writing from a position of poverty might be able to find only ten minutes or half an hour at a time in which to compose new work (and then similar brief blocks in which to revise it). But the intensity, urgency, and quality of her work might be just as worthy of literary attention as a well-written novel. The compression of her prose, rather than being denigrated as an inability to handle greater textual heft and complexity, might instead merit praise for its economy. Her vision might be fresher and more revealing than that of the latest fat tome about upper-middle class families, their purchases, their lusts, and their woes.

Longer isn’t better. Sometimes it’s merely loose and rambling and self-indulgent. Or showy. Sometimes the impact of an entire book isn’t as strong as that of a powerful, incisive flash piece. Small doesn’t mean insignificant or reductive. Think atoms. DNA. Brief pieces can explode.

To take full account of this insight, we need a paradigm shift in how we see, how we judge, how we talk and write about literature. We need to let ourselves respect the lure and power of the small.

—

Joy Castro is the author of the memoir The Truth Book, the literary thriller Hell or High Water,and the essay collection Island of Bones. Her work has appeared in Fourth Genre, Seneca Review, and The New York Times Magazine. She teaches creative writing, literature, and Latino studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

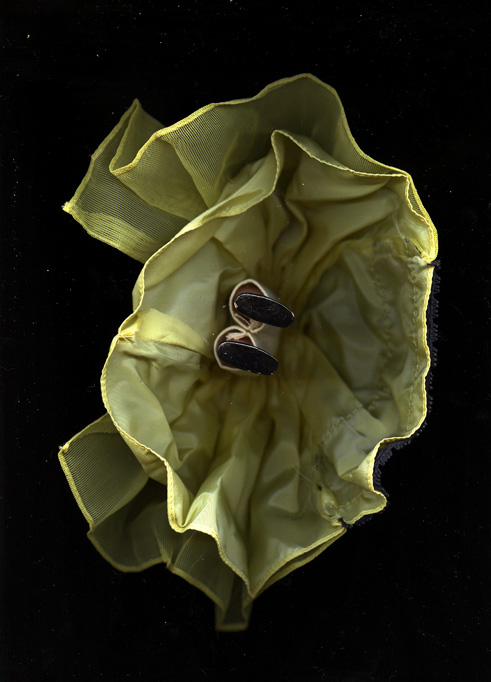

Artwork by Gabrielle Katina

11 comments

lucinda kempe says:

Sep 20, 2012

“We need to let ourselves respect the lure and power of the small.

—”

Yes, I believe that too. Thank you for saying it so well.

Andrea says:

Sep 25, 2012

I have 30 minutes to write this morning (a banner day!) between sending my daughter off to school and going grocery shopping, and all the rest of my stay-at-home responsibilities. But I’m making the choice to use some of my precious writing time to say “thank you” for this piece. However, do you agree that it often takes at least twice as long to compose a flash piece that must pack a punch than it does to write a 2000-word piece? Most of my essays are under 1000 words (including one that will be Brevity-length) and I’ve been working on it now for two years to get it right. (And thank you for writing a concise, brief piece on this topic since I haven’t been able to read an entire essay/article in a long time.)

{the life} The Friday social | The Life & Lessons of Rachel Wilkerson says:

Sep 28, 2012

[…] On Length in Literature [This essay from Brevity Magazine kind of made my heart explode.] […]

Joella says:

Oct 5, 2012

Think poetry.

Peggy Rosana says:

Oct 11, 2012

This is an elegant manifesto that I can share with my second language students who are as terrified as I am to pick up the pen.

Drevlow says:

Nov 29, 2012

I fully agree that writing a long novel (or even a novella) takes a lot of spare time for writing, and I am not someone who values “heft” of a novel over other characteristics like emotional truth, etc., but I am troubled by the statement that “when we talk about the length of a work, we need to acknowledge that we are talking about privilege. Not excellence, not talent. Privilege.” Are to say that there is no talent in the ability to construct a narrative that compels the reader for, say, seven hundred pages? I’m not here to tell you that a seven-hundred-page novel is inherently better than a two-hundred-page novel or even a ten-page-short story, or for that matter a twenty-line poem. But to say, writing for length is simply a matter of the privilege of spare time, is to say that any writer with enough spare time could write a compelling opus. You may, yourself, be equally adept at longer works and shorter works, but that in itself is a talent that not everyone has. The same way not everyone who writes great prose can write great poetry, there are also people who are simply more talented at writing compelling novels that go on for a thousand pages. There is a skill to running sprints in the same way there is a skill to running marathons. Yes, there is probably an over-emphasis on the big novel in the literary culture, the same way there is probably an over-emphasis on non-fiction (over fiction and poetry) in the general reading culture, but we don’t have to demean one talent or art form when we praise another. I love Raymond Carver and David Foster Wallace and I think they were both incredibly skilled at what they did best. I don’t need to degrade Raymond Carver to say that I am in awe of writers who can sustain a compelling story over the long haul. I am equally in awe of the way some writers can convey so much with so little. I love poetry and prose; they demand different skill sets and their aesthetic appeals to me at different moments and on different levels. But then, I guess this view of things does not get headlines or create a buzz in today’s reactionary world of snark, antagonism, and sensationalism in everything.

LK says:

Dec 18, 2012

Yes. Brevity should not detract from artistic merit, nor should length necessarily add to it. I often think of John Cheever’s short story “Reunion,” a three page story that has amazing thematic weight despite its short length.

However, a short story by Cheever or Raymond Carver cannot hope to capture the same breadth of experience — the same richness! — that a sprawling, virtuosic novel can. You look at, say, Raymond Carver’s best work (I think it’s Cathedral, 20-25 pages or so) and then Charles Dickens’ best work (Bleak House, in my opinion, 700-800 pages or so) and frankly, the aesthetic achievement of the novel blows the short story out of the water, great as that short story is! There is a vividness, a richness, in a great sprawling novel that is unmatchable in shorter forms.

I’m not against appreciating brief pieces, and judging them against other longer forms. But the fact of the matter is that only the very best short stories (Dubliners, Chekhov, Flan O’Connor, In Our Time, Carver) can even hope to be mentioned in the same class as a Dickens or Pynchon magnum opus. In fact, of those I just mentioned, only Joyce’s “The Dead” stands out beyond the realm of the short story.

As to the point about privilege; obviously being privileged helps in most enterprises, but the notion that when we’re talking about long novels, we’re talking “not about talent, not about excellence,” but about privilege exclusively, is disconcerting to hear. When evaluating aesthetics, and judging a text on its properties — the very essence of close reading! — these social factors are unhelpful. The canon is littered with aristocratic writers who wrote excellent sprawling novels, and poor and middle-class writers who wrote excellent sprawling novels. Discussing the social circumstances of the writer in the context of aesthetics pollutes and politicizes aesthetic study, which should be concerned primarily with beauty in art, not the fixations of social science — race, class, gender. Those are ancillary matters.

I know that when I read Dickens, or Joyce, or Pynchon, or Faulkner, or Woolf, or Malcom Lowry, it is not the author’s privilege that jars my conscience. It is their excellence and talent. Yes, length can be an aid to their literary mission, but with those authors, it is the excellent artistry within that form that COMMANDS my aesthetic reverence.

Memoir or Diary? | Story Arch says:

Mar 11, 2014

[…] On Length in Literature: Did you know that she was a single mom putting herself through undergrad and grad school? I find this incredible inspirational as I am approaching my graduation date and nearing grad school application. She has her student loans paid off and did it through teaching and writing! […]

Serena says:

Jun 13, 2014

There is great beauty in this story and great inspiration. A lot of times, it takes courage to spend twenty minutes here or there to write, to give in to our artistic selves, to live. I think that pieces of literary quality of any and every length are pieces capturing the human experience for all to love. Wonderful essay.

How We Spend Our Days: Joy Castro | catching days says:

Aug 1, 2015

[…] Be happy with small. Some days you can only write a little. Some days you can’t write at all. Leisure, class, and the absence of family responsibilities have a great deal to do with who manages to find time to write every day. I was a no-book writer for several years, and then a one-book writer for several more. Don’t flagellate yourself if you’re not one of the lucky ones. Do what you can, and persist.3. What is your strangest reading or writing habit? […]

mary says:

Sep 16, 2016

Brilliant essay! But I would like to add a couple of things:

The first great English novelists were women, and the novel was considered a natural form for a woman to write because she could pick it up and put it down again, writing in the snatches of her day– as Jane Austen did, to give one example.

Among male novelists, many had jobs outside the home, and some (Dickens, for example) wrote in short pieces to strict deadlines, in order to make a living.

At a recent class in the library, writer Patricia Dunn stated: “If you have ten minutes every day, you can write a novel”. I agree wholeheartedly!

It’s important to recognize the love, skill, and craft writers pour into short forms. But form and content go to creating a single piece. The excellent writer, regardless of their outside circumstances, will choose the right form for the story they want to tell. Novels are not better than flash fiction; flash fiction is NOT easier to write than novels!

Serena, I love your comment! To the original poster, I hope you don’t mind my chiming in. I am here via a link on Twitter.