My mind speaks through drawing – a perk of painful childhood shyness. Afraid to talk, scared of crowds, I stared at paper and doodled until a comprehensible universe formed on the page. Doodling is still my escape route away from awkward human interactions.

My mind speaks through drawing – a perk of painful childhood shyness. Afraid to talk, scared of crowds, I stared at paper and doodled until a comprehensible universe formed on the page. Doodling is still my escape route away from awkward human interactions.

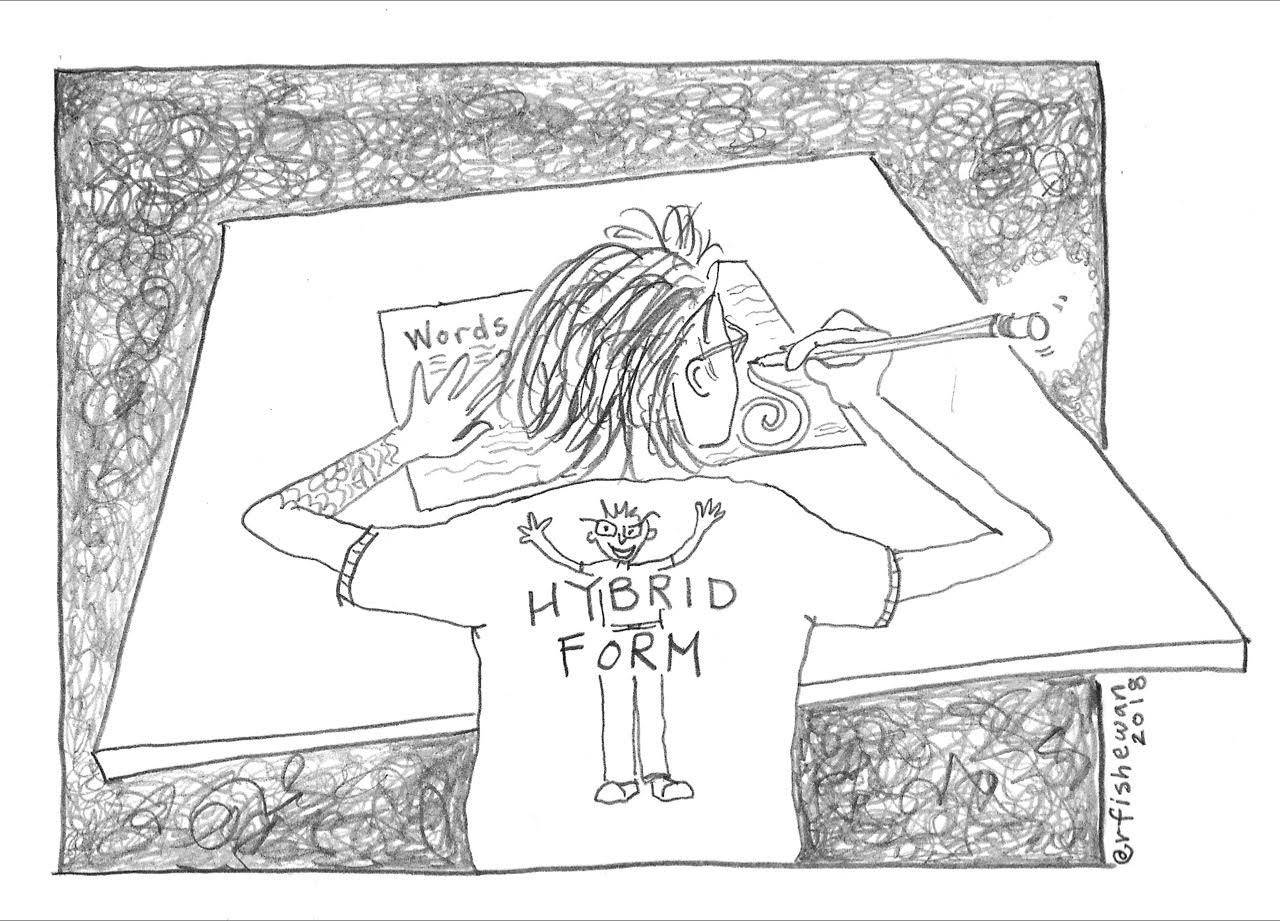

As an adult, I applied my compulsion to draw to creating hybrid-form work. When I drafted the text for my new memoir, By the Forces of Gravity, I needed to see the scenes, to help me discover the right words to describe them. With my pencil, I drew right on top of my draft pages. As it happened, these drawings became essential to the final story; the book contains over 200 cartoons paired with free verse. But had I known while I sketched that these scribbles were destined for publication I wouldn’t have been able to draw with such abandon. My brain would’ve started in on its critique of my skills. “Your foreshortening sucks!” “Where are the shadows?” “Do you understand perspective one tiny bit?”

My brain talks too much.

I’d like to share a drawing secret, so you can avoid your own brain chatter: Anyone can draw. That’s right. Anyone. Can. Draw.

Not only that, but drawing can enrich your work. Right now. Without formal training. Regardless of internal (or external) negative criticism. The truth is simple: If you can hold a pencil, you can draw.

Not only that, but drawing can enrich your work. Right now. Without formal training. Regardless of internal (or external) negative criticism. The truth is simple: If you can hold a pencil, you can draw.

“But wait!” your mind screams. “Stop! You suck at drawing! Remember what that kid in third grade said about the bunny you drew? It was terrible! Put the pencil down now!”

Tell your mind to pipe down.

Distract it with a favorite song.

Run your brain through worst-case scenarios.

Think about it. If you draw, will cartoon police spring out of your closet and drag you off to the Prison for Errant Doodlers? No, brave soul, the worst thing that can happen is you’ll feel a sense of displeasure (which you may for a moment mistake for intense self-loathing). Just like when you write something that displeases you. And what do you do when you write words you don’t like? You write more words. Problem solved. However, it may happen that, as with writing, you dig into true pain as you draw. As with words, the digging hurts, but it’s a good hurt, a healing hurt. In any case, no cartoon police.

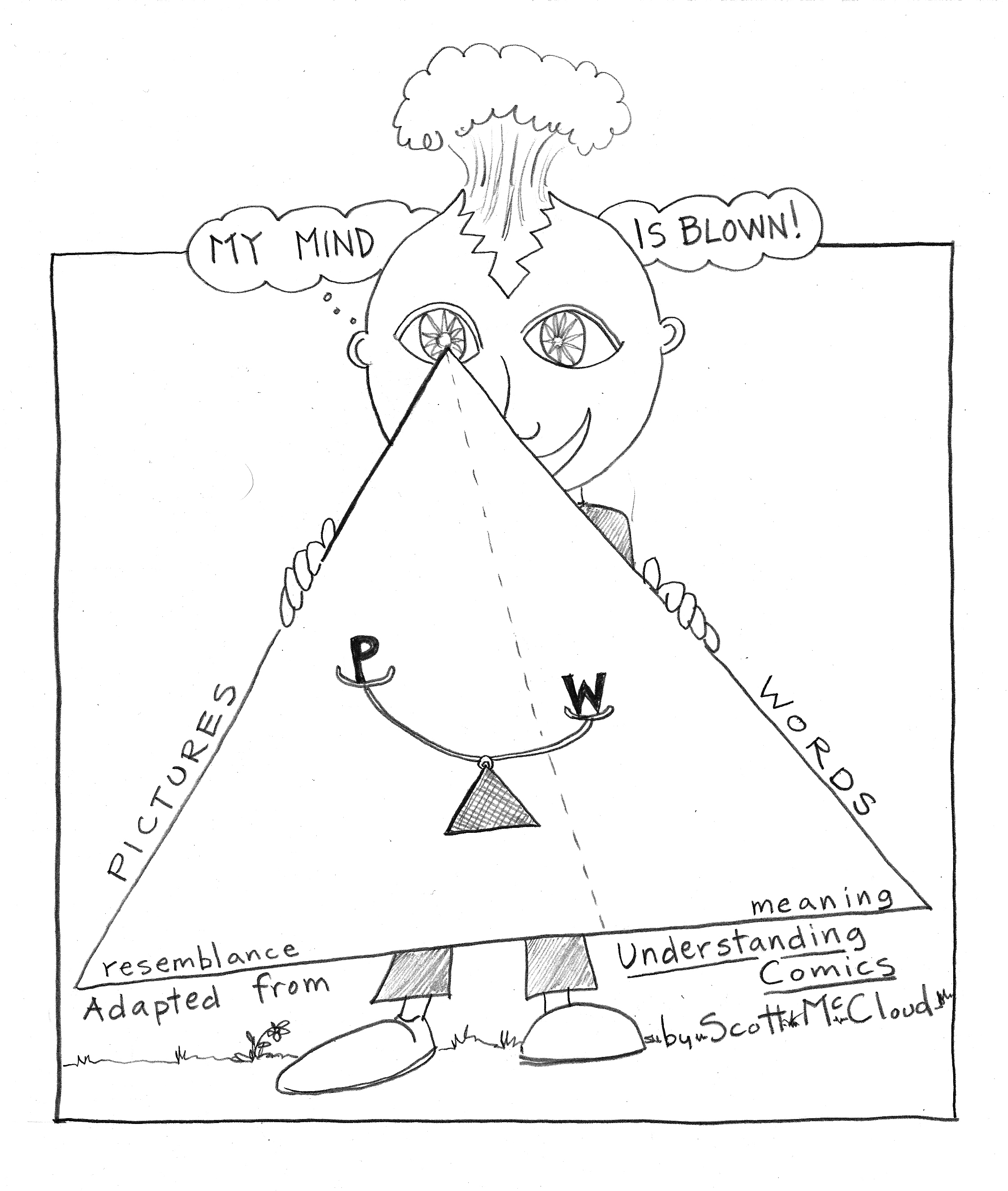

So now that you’re a doodler, what’s next? When you make marks on a blank page, you create meaning, either through words or pictures. By hybridizing these two mechanisms for creating meaning, you can explore alternative ways to communicate thoughts and stories. Like text-only hybrid work, you can mingle two or more distinct genres, and how you mingle them will determine the structure of your work (be it essay, novel, memoir, poems or…). In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud uses a triangle to illustrate the relationships between words and pictures on the page. These relationships influence structure. McCloud notes that “the mixing of words and pictures is more alchemy than science.” A form that is best for your story can be arrived at through experimentation.

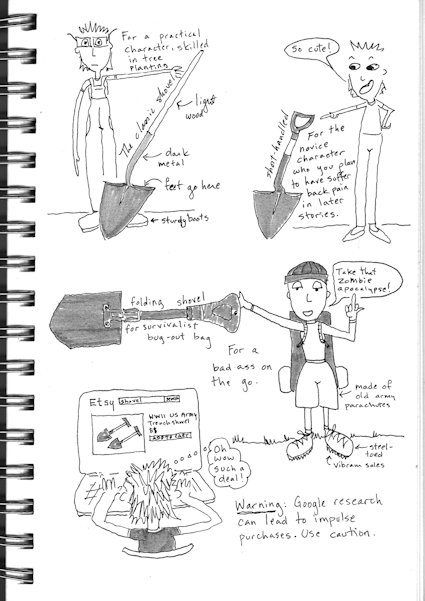

Drawing can inform your writing process or become a part of your completed work. Process drawings include character sketches, maps and story boards. Draw character sketches and pin them up near your writing space (or carry them in your notebook if you’re a writer on the go). These drawings will help remind you of how your character stands, dresses, expresses anger or joy. Sketch the things they carry, their friends, a plan of their bedroom, a map of their town.

Drawing can help you think through how ordinary things work. If you’re writing a scene in which your character is, say, planting a tree, make study sketches of shovels. Draw a tree hole. Google “planting a tree” and hunt around until you find what you like and draw it. Make notes. Even better, go outside and plant a tree. Stop every so often to draw what’s happening. Drawing invigorates the nerves in your fingers (there are tons of them) and these nerves send signals to your brain to help you remember what you’re touching. This helps you notice details that your eyeballs might miss.

Drawing can help you think through how ordinary things work. If you’re writing a scene in which your character is, say, planting a tree, make study sketches of shovels. Draw a tree hole. Google “planting a tree” and hunt around until you find what you like and draw it. Make notes. Even better, go outside and plant a tree. Stop every so often to draw what’s happening. Drawing invigorates the nerves in your fingers (there are tons of them) and these nerves send signals to your brain to help you remember what you’re touching. This helps you notice details that your eyeballs might miss.

Storyboards are images, usually small quick drawings called “thumbnails,” paired with text that outline the narrative. Hayao Miyazaki, a creator of animated films, has published beautiful story boards. I can’t read Japanese, but I can still learn from the structure of his pages.

Visual hybrid-form work can be categorized structurally, with a focus on word/picture relationships.

The categories include:

Juxtaposed: This is how I constructed By the Forces of Gravity. Narrative free verse is paired with cartoons, illustrations or comics to give the words and pictures room to breathe, so readers can decide what to give their attention to. By maintaining distance, the words and pictures say the same thing, for emphasis, or they say different things, to provide perspective. It’s like two people standing side-by-side, each one a distinct person, but creating resonance by their closeness.

Juxtaposed: This is how I constructed By the Forces of Gravity. Narrative free verse is paired with cartoons, illustrations or comics to give the words and pictures room to breathe, so readers can decide what to give their attention to. By maintaining distance, the words and pictures say the same thing, for emphasis, or they say different things, to provide perspective. It’s like two people standing side-by-side, each one a distinct person, but creating resonance by their closeness.

Braided: Like the text-only braided essay, except in this case one or more of the threads is visual.

Braided: Like the text-only braided essay, except in this case one or more of the threads is visual.

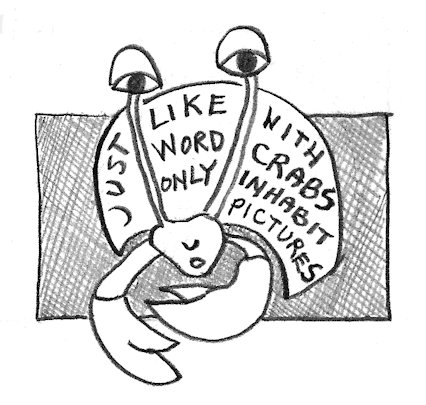

Integrated: Options abound! Comics art integrates words and pictures. Comics poetry mingles words and pictures as well, but is often less narrative, like lyric essays. Illuminated manuscripts turn words into elaborate images. Hermit crab essays that appropriate an image could be fun to try, though it kind of Klein-Bottles my head, thinking about what this might look like. I tend to fill space in drawings with words. This is another form of integration.

The balance between words and pictures influences the reader’s experience, another reason I decided to use juxtaposition in my memoir. I wanted readers comfortable with words to feel as welcome to the pages as consumers of cartoons. I considered creating a more traditional graphic novel form, but those take tons of planning and I’m not a planner, word lovers might not pick up the book, and the voice in the poems would have been lost.

The balance between words and pictures influences the reader’s experience, another reason I decided to use juxtaposition in my memoir. I wanted readers comfortable with words to feel as welcome to the pages as consumers of cartoons. I considered creating a more traditional graphic novel form, but those take tons of planning and I’m not a planner, word lovers might not pick up the book, and the voice in the poems would have been lost.

Here are two essential ways to integrate drawing into your writing life and create hybrid visual work:

- Carry a notebook you’re comfortable doodling in and use it. Draw from your head and from what you see around you. Don’t critique, just draw. Make notes on or beside your drawings (helpful for later when you can’t remember what you’ve drawn).

- “Read” hybrid work. Do more than read the words; study the images and examine the relationship between words and images. Figure out what touches your heart. Is it the line work, contrast, composition of the pages, use of color? Think of drawings as a visual language. With written language, you have favorite authors, favorite books. It’s the same with hybrid visual work. Seek out and study what moves you. For some examples, you can visit my website and the list of word/drawing books with linked book titles.

____

Rebecca Fish Ewan is a poet/cartoonist/writer and founder of Plankton Press, where small is big enough. Her writing, cartoons and hybrid-form work appears in Brevity, Punctuate, Under the Gum Tree, Mutha and Hip Mama. She makes zines and teaches in The Design School at Arizona State University (her creative writing MFA home). She has two books of creative nonfiction: A Land Between and By the Forces of Gravity: A Memoir. Rebecca grew up in Berkeley, California and now lives in Tempe with her family. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter: @rfishewan.

11 comments

Joanne Marie Lozar Glenn says:

Sep 17, 2018

Rebecca, this is one of the most interesting and different craft essays I’ve read. I love how it sparked my brain (whether that will translate to my pencil might be another story, but one worth trying :). It was so fun to read this, so nice to meet you at HippoCamp and to attend your presentation. Thank you for putting your work out into the world.

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Sep 18, 2018

Thanks Joanne! ??? I hope to see you at HippoCamp 2019 ?

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Sep 18, 2018

Oh darn my emojis were translated into question marks 🙁

NERDBOXER says:

Sep 20, 2018

This is the first post I read on Brevity Magazine and I am really impressed. This post reminds me of “The Back of the Napkin” by Dan Roam. Your delivery is comforting and easy to follow. It feels good to know I am not the only person who has been bullied by their inner critic. I will continue to look for your posts here as well as on Instagram. Nice work!

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Nov 10, 2018

thanks! 🙂

Jan Priddy says:

Sep 21, 2018

Love this. For the same reasons you name, I regarded myself as an artist. I am attracted to covers, to publishers who chose beautiful covers. I have not gone so far and admire you terrifically for finding a way to embrace your own inclinations in such a wonderful way! I will look for your work.

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Nov 10, 2018

thanks! 🙂

JoAnne Lehman says:

Nov 2, 2018

I’ve said this on Amazon and in a personal FB post, but I want to say it here too: By the Forces of Gravity has blown my mind! Also, I too am so glad I met you at HippoCamp, and I hope to see you there next year. And this post inspires me to think about doing more than abstract doodling as I write CNF this year.

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Nov 10, 2018

I love HippoCamp too! I hope I can make it there next year. Thanks so much for the kind words about By the Forces of Gravity. 🙂

Barbara Harvey-Knowles says:

Nov 3, 2018

I love your work and have tried using a braided writing/drawing hybrid style. I am definitely not an artist, but parts of my life haven’t been beautiful either. What I have thrown out as not being “good enough” artistically, perhaps reflects how I feel about my life at times. I was so amazed hearing you speak at HippoCamp. I’m going to try my hand at this again.

Rebecca Fish Ewan says:

Nov 10, 2018

Thanks! I love the braided essay form and weaving drawing into it too. I hope you keep drawing! And that I can make it to HippoCamp next year! 🙂