In the following Q&A, contributor Brendan O’Meara and author Tom French talk about journalism and how the writer uses tension in the story to create a dramatic narrative.

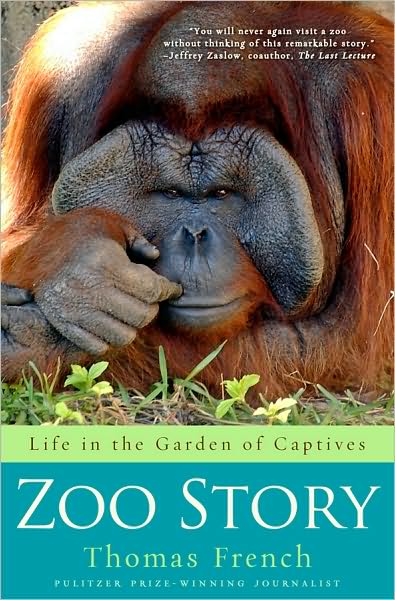

In July 2010, Hyperion released Tom French’s book Zoo Story: Life in the Garden of Captives. Within weeks, the book hit the New York Times bestseller list, and French appeared on NPR’s Talk of the Nation and the Colbert Report. A Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, French spent twenty-seven years as a reporter and editor on the St. Petersburg Times. There he became nationally known for his innovative serialized journalism narratives. Including Zoo Story, four of the series became full-fledged books. French is currently on the faculty of Goucher College’s creative nonfiction MFA program, and he is the Riley Endowed Chair of Journalism at Indiana University School of Journalism.

In July 2010, Hyperion released Tom French’s book Zoo Story: Life in the Garden of Captives. Within weeks, the book hit the New York Times bestseller list, and French appeared on NPR’s Talk of the Nation and the Colbert Report. A Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, French spent twenty-seven years as a reporter and editor on the St. Petersburg Times. There he became nationally known for his innovative serialized journalism narratives. Including Zoo Story, four of the series became full-fledged books. French is currently on the faculty of Goucher College’s creative nonfiction MFA program, and he is the Riley Endowed Chair of Journalism at Indiana University School of Journalism.

Q. What is Zoo Story about?

A. Zoo Story is about freedom and its limits. It’s obviously about zoos and captivity and the sort of tangled relationship between humans and other species. But in the end it’s about our version of freedom and our conflict with nature that we want to both exalt nature and control it.

Q. You begin the story with elephants, and you end it with game wardens. Why so much emphasis on elephants? Is it because they are at the ethical crossroads of captivity and freedom?

A. The surface reason is those elephants on that plane, their arrival at the zoo, is the central spine of the story. It’s also a focal point for the controversy and the tension that a zoo embodies. The arrival of these elephants at Lowry Park signals the shift from the zoo trying to become a midsize zoo to a big city zoo.

Deeper than that, elephants are a species that challenges the tension of the zoo most profoundly because in the wild they wander for all these great distances. They’re very intelligent, very emotional, very aware. They have memory. These wild elephants were plucked from Africa and dropped into captivity inside a zoo that’s trying to do a good job and take care of them.

Q. I found your subtitle interesting: Life in the Garden of Captives. On the one hand garden elicits a sense of paradise, but you wouldn’t necessarily connect it with captivity. What was the idea behind that?

A. There’s a tension between those two words. Actually most zoos are run by “zoological gardens.” Paradise originally meant “walled garden.” There are so many good things going on at the zoo, so much care is expended to try to do the best for these species and to make these species thrive. It’s very problematic because the moment we start to manipulate nature, we’re playing God. And we’re not God.

Q. What was the impetus behind exploring the inner workings of Lowry Park?

A. I read Life of Pi in the summer of 2003. There’s a passage fairly early, where the narrator realizes our notions of freedom are in conflict with this romanticized misconception humans have about zoos. I love the whole book, but that passage stuck with me in terms of being a reporter. I just realized that I never read a really good indepth report of what life is like inside a zoo. I wanted to know more.

That was good because we’ve all read journalistic works about whorehouses, police stations, city hall, public schools, nursing homes, hospitals. We’ve read a lot about these different institutions, but this seemed like an institution that really needed an indepth journalistic approach that I’d never seen.

Q. This started as a serial narrative for the St. Petersburg Times. So what was the process in expanding this into a book?

A. The first two-thirds of the book, the story part, is very much like it was in the series. But this whole new way it turns in the last third with Lex [Salisbury, Lowry Park’s CEO] is that in the book the elephants are central. Lex’s vision of what he wants to do with this zoo and the cost to other people in the zoo and some of the animals and himself really become the central organizing arc of the book. That’s really different in the book.

I went back and read everything I could about zoos, the history of zoos, the politics of zoos, and I read about the different species. I read a ton on elephants in terms of books, research on elephants, their physiology, their communication, their reproduction. I read a ton about chimps and tigers as well. So I grounded all that first-hand reporting with a ton of research.

Q. The first two-thirds of the book dealt with the animals and the last third focused on Lex Salisbury. Why that structure?

A. Lex’s ambition, long before Lex was forced out, was problematic. It did a lot of good things for the zoo. I say in the book that a lot of people who don’t like him call him a visionary but that vision came at a real cost. So what happens? First it costs others, some of the animals, some of the people there at the zoo, ultimately (a very classic story), it costs himself a lot. I’m glad I had time to watch it play out and then to build a chronicle in the book, because I think it was really important.

Lex is the classic alpha drawn to define for himself the boundaries. Ultimately it cost him dearly.

Q. “Undertow” and “Freedom” are two of the most powerful chapters in the book and they’re back to back. Give me a sense of how hard it was to write and report on the deaths—some would say murders—of Herman and Enshalla.

A. I really had gotten close to both of those animals. I’d been following them for years when they had both died. I wouldn’t say they were murdered. I know some people would, but that’s not a word I would use. So when they were killed, my first thing was that it just ripped me apart. I love both those animals. It was heartbreaking. But once I got done being heartbroken, I realized I had to sit down and write it. But it was hard. I loved those animals.

Q. The first line of the book is great: Eleven elephants. One plane. Hurtling together across the sky. How did that come to you?

A. Sometimes you really struggle with your opening and other times it’s there right in front of you. This one I was actually here at Goucher [College], and I was getting ready to do my reading. I had just finished my first six to eight months of reporting, and I just wanted to tell people about what I was witnessing during my reporting. I hadn’t written anything yet so I took one day, in between our workshops and lectures, and I wrote it quickly. I was on deadline because I had to read that night. That line just bubbled up and there it was. It was very close to the very first line that I wrote that day.

Q. Obviously the animals play a large part, but did you get a sense that the animals weren’t the only ones held captive?

A. That’s one of the themes of the book that we have this romanticized idea of freedom but none of us is really completely free. We all have predators to deal with and challenges, and nobody is free in a classic sense, so to watch all the different constraints that are on us was really right there in my mind from the start.

For instance, to watch Brian French, the head elephant keeper, his love of those elephants and his dedication to them, I think I say it directly, “if they are his prisoner then he is theirs as well.” Because he lives with them, he sleeps beside them in that cot.

Freedom can be really dangerous, can be deadly. Enshalla, when she stepped out of her den, that’s the first time she’s ever been free in her life, and she had never been at greater risk.

Everything you want to write about is waiting inside a zoo: life and death, sex, power, money, all of it is there intersecting in one fairly small world.

—

Brendan O’Meara lives in upstate New York and is circulating his narrative nonfiction work, Six Weeks in Saratoga: Inside North America’s Most Prestigious Thoroughbred Horse Racing Meet, among publishers. His writing has appeared in SN Review, Blood-Horse Magazine, Paulick Report, Horse Race Insider, Spirit of Saratoga, and other publications.