Among the least pleasant chores of a writing teacher: dissuading students of the notion that what sounds good in a piece of writing is, necessarily, good. It’s the part of my job that I most dread and dislike, the part where I’m forced to play bad cop opposite a classroom full of good cops who reply, “But I liked it!” Yes, yes, I say. I know you liked it. But it doesn’t mean anything, or it doesn’t mean what you meant, and it’s not precise (which is why it doesn’t mean what you meant, assuming it means anything).

Inexperienced writers, especially young ones, often sacrifice meaning for effect. Sound and sense are divided, or anyway not faithfully joined. And so, for them, it’s possible for something to “sound good” even when what is being said lacks clarity, rigor, precision, or even allegiance to truth.

Having once been a young writer myself, I was no exception to this tendency. I fell in love with words not for their meanings, but for their sounds. Like most healthy young people, I was a sensualist, a glutton for whatever tickled and otherwise amused or delighted my senses, for things sharp, bold, bright, piquant, dazzling, smooth, saucy, bitter, sour, sweet—for colors and smells and textures. I cared little about what lay hidden and invisible under those surfaces, for their precise meanings and implications. Those depths could come later; meaning could wait. Life offered too many sensual delights on the surface to bother with hidden things. Why dig under leaves and moss when the leaves and moss themselves were so alluring?

This was how I felt when I was a younger writer, and it’s common for young writers today to feel this way. The words “truth” and “meaning” weigh grimly and onerously upon young hearts and minds. They imply drudgery, duty, joyless determination, pedantry, and other things antithetical to youth, to freewheeling pleasure and delight. No fun at all.

I still remember the poems I wrote when I was in my early twenties, when I’d just started writing, when I was still in the throes of a seduction by words, verses aggressively devoid of meaning, but that tickled my senses with impudent word play and fancy rhythms. Sat upon the way vast upon deep beyond the tree wide and wind … That sort of stuff. I wrote oodles of it, endlessly amused by the sound of my own voice (or what I thought of then as “my voice,” but was, in fact, a distorted echo of Hopkins and Thomas and other poets whose rhythms and sounds I appreciated, but whose meanings rarely impressed me).

I dared to show some of these verses to my father—an engineer and inventor who also wrote books. I remember his loud “aughs” and “ughs!” and other guttural sounds of disgust that he emitted while suffering through them. At last he cast his verdict, saying, “Peter, you must learn never to write for effect.” I defended myself. “What do you mean?” I said. With an exasperated sigh my father said, “Words have meanings. Otherwise they’re meaningless!”

I couldn’t feel too bad. After all, this was the same father who had it in for Marcel Proust. “His metaphors are all wrong,” Papa once complained to me. “I’ll give you an example. At one point Proust writes something to the effect that the leaves of a tree give off a scent when ‘allowed to’ by the rain, ‘la parfum que les feuilles laissent s’échapper avec les dernières gouttes to pluie.’ It makes no sense, not if you think about it. The rain doesn’t ‘allow’ or ‘permit’ anything. That sort of language just doesn’t work, not for me.”

As an undergraduate at Bard College, and heartened by my having something in common with Proust, I presented a sampler of my fledgling verses to Robert Kelly, then in all respects an imposing poet. He read through them quickly and, nodding, announced, “I find your poems arbitrary in every way.” Mr. Kelly didn’t care what my poems sounded like. He saw little in them beyond what they meant, or failed to mean.

Back then I considered Kelly’s verdict harsh. Now, thirty years later, I find it just and generous. I feel similarly toward Frank Conroy, the famous Iowa Writers Workshop director who, in a summer workshop, having arrived at the word “preponderance” within my story’s first paragraph, tossed the manuscript over his shoulder. In another story of mine he objected to a sentence that had “sparks” of spittle flying out of an angry character’s mouth.

“What’s wrong with that?” I asked.

“What’s wrong is it doesn’t say what you meant.”

“Yes, it does.”

“What did you mean?”

“I meant that little flecks of spit are shooting out of the guy’s mouth.”

“That’s not what you wrote.”

“Yes it is!”

“You wrote sparks, ‘sparks’ of spittle,” Conroy said. “You meant flecks. Write flecks.”

Sparks of spittle. It still sounded good to me. But Conroy wasn’t criticizing my sound; he was asking me to be precise; he was insisting that I say what I meant.

Now I am a teacher myself, the “veteran” author insisting upon the very qualities that I resisted when I was a young writer: truth and meaning, clarity and precision, rigor and authenticity. At times I ask myself: do you really want to do this, Peter? Do you really want to devote so much of your days to dampening the still-fresh-as-wet-paint enthusiasms of talented young people with your fogey, finicky values? What good will come of it? Why not shut up and let them have their fun? Let them express themselves.

Then I remind myself: these are not ordinary young people dabbling in their diaries. These are young people who want to be good writers, who are devoted to and serious about the craft of writing. At their age, in their shoes, would I have preferred to wait ten or fifteen years to discover what took me ten or fifteen years to discover? Namely that, though the immediate delight of a sentence may lie in its texture, shape and sounds, those pleasures last only as long as the sentence itself. But for the same sentence to stay with us, to have lasting value, it must otherwise earn its keep. It must mean something and mean it precisely.

So I find myself saying to my students time and again—especially when they’ve written something extremely clever, something that grabs the attention and wins the approval of most of their peers, something that sounds really good:

“Yes,” I say, “but what does it mean?”

And then—in words simple and straightforward and pure and true, they tell me.

“Write that,” I suggest.

They look at me like I’m kidding.

“No,” I say. “Write that. What you just said. That’s what you meant, after all, and that’s what you should write.”

Occasionally a student will object: “But it isn’t as good!”

“That depends,” I say.

“On what?”

“On how willing you are to divorce beauty from meaning.”

In ways, writing is like falling in love. When we’re young, superficial qualities—hair, eyes, skin—mean everything. Only as we grow older do most of us recognize that what’s inside matters at least as much, if not more. On the other hand, when it comes to words, anyway, who says we can’t have both? Where is it written that sound and sense—music and meaning, precision and poetry, truth and delight—can’t be joined in holy matrimony on the page? Isn’t the whole point of writing, after all, to marry them?

The grey warm evening of August had descended upon the city and a mild, warm air, a memory of summer, circulated in the streets. The streets shuttered for the repose of Sunday, swarmed with a gaily colored crowd. Like illumined pearls the lamps shone from the summits their tall poles upon the living texture below which, changing shape and hue unceasingly, sent up into the warm grey evening air an unchanging, unceasing murmur.—James Joyce, “Two Gallants”

Meaning and sensual delight can and often do go hand in hand. But they won’t join hands unless we exercise rigor and resist total seduction by sounds and surfaces.

__

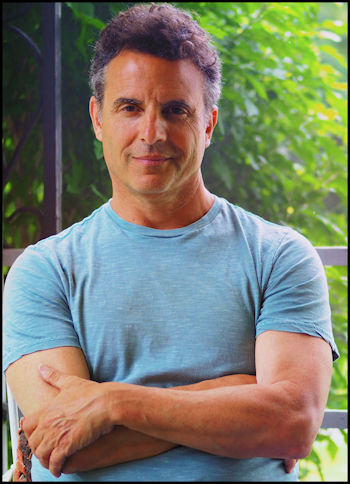

Peter Selgin is the author of Drowning Lessons, winner of the 2007 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. He has written a novel, two books on the writer’s craft, an essay collection, and children’s books that he illustrated. His recent memoir, The Inventors, was tabbed by The Library Journal as one of the best memoirs of 2016. “It is,” the reviewer wrote, “a book destined to become a modern classic.” He teaches at Georgia College & State University in Milledgeville.

1 comment

Cath says:

Apr 21, 2022

Don’t mean to be rude but maybe your father would have been less sniffy about Proust if he’d translated the French correctly! The subject is the leaves, not the rain, and “laisser échapper” doesn’t have a sense of “permit” – it just means let out or release. The leaves are releasing their scent with each drop of rain.