There are moments in my small rural life that make everything else fall away. These moments make for a good life—sitting around the dining room table with my children and friends, drinking wine or cider, telling stories about Edward Abbey or anarchy or the dissent of the western environmental activist, all while the fire burns in the stove and candles shaped like hippos, turtles, and butterflies drip wax onto the table. Or when I walk up into the woods with my daughter where she finds warped river teeth and turkey tail mushrooms and ferns as big as her head and she whispers to me that Gargamel must live nearby, but maybe just some bears and deer. Probably raccoons. Or when I chop wood with my son, the day cold and clear, and we squabble over the acuity of the axe and he insists on splitting the wood himself, and as I let go of the worry and control, I watch the boy who will grow into a man here, shaped by the land we live on. These are the moments I cherish, and whatever version of these moments are yours to value as well, these are the occasions which Brian Doyle writes with grace, beauty, and polish in Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace.

There are moments in my small rural life that make everything else fall away. These moments make for a good life—sitting around the dining room table with my children and friends, drinking wine or cider, telling stories about Edward Abbey or anarchy or the dissent of the western environmental activist, all while the fire burns in the stove and candles shaped like hippos, turtles, and butterflies drip wax onto the table. Or when I walk up into the woods with my daughter where she finds warped river teeth and turkey tail mushrooms and ferns as big as her head and she whispers to me that Gargamel must live nearby, but maybe just some bears and deer. Probably raccoons. Or when I chop wood with my son, the day cold and clear, and we squabble over the acuity of the axe and he insists on splitting the wood himself, and as I let go of the worry and control, I watch the boy who will grow into a man here, shaped by the land we live on. These are the moments I cherish, and whatever version of these moments are yours to value as well, these are the occasions which Brian Doyle writes with grace, beauty, and polish in Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace.

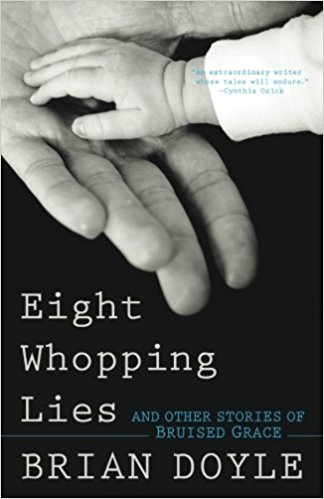

In Eight Whopping Lies, one of Brian Doyle’s last books before his death early in 2017, Doyle, a frequent Brevity contributor, offers fifty-eight short essays on a variety of subjects, some barely more than a page. These essays orbit around such topics as brotherhood, family, murder, rosaries, lies, pants, birds, guilt, love, but together, the essays create something akin to a book of prayers, a celebration of life in all of its forms. Doyle writes these pieces in simple, but profound short prose with a voice that is distinctly and entirely Brian Doyle. Each essay is like a private note to the reader. It’s as if, as I read, Doyle is telling me stories by the woodstove with wine and Edward Abbey in the corner laughing it all off. I found myself reading many of the essays aloud to my husband both of us shaking our heads, smiling, “Yes, Yes, Yes. That’s right. He’s so right.”

To read a Brian Doyle essay is to understand story. To feel something, anything. I’m a better human after reading a Brian Doyle essay. I’m a better writer after reading a Brian Doyle essay. And he does all this through brilliant mechanisms that only Brian Doyle can employ. For instance, lists. Doyle’s sentences are epic and rambling, but always, moving toward a finish line that is unexpected and beautiful. In “Illuminos” he writes about his son (he writes very tenderly about his family in this entire collection), “The third child held hands happily all the time, either hand, any hand, my hands, his mother’s hands, his brother’s hands, his sister’s hands, his friends, aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents and teachers, dogs and trees, neighbors and bushes…” and on. A lesser writer than Doyle would not be able to accomplish the precision of the rhythm and repetition as he does. Doyle stretches the sentence, uses language in unusual ways, answers questions I didn’t ask in the first place, but for which I need an answer anyway. The essays in this book ask you to pause, reflect for a moment on the themes: what did he just say of God, of faith, of all of us who thirst—oh yes, that’s right, and then the clarity of meaning and purpose washes over you. Often, the titles of the essays are prompts as Doyle jumps right in to offer some profound human insight or gesture. In “On the Bus” he begins, “Here’s a story for you. Here’s a story that you will think about the rest of the day” and you do. The story endured as I picked up my son from school and boiled water for pasta.

Doyle surprises the reader in ways you don’t expect. He’s dogmatic, without being dogmatic, or perhaps I’m mistaking it for confidence. He believes and he believes deeply. In one of my favorite essays in the book “A Tangle of Bearberry,” Doyle writes of driving with his mother to a summer job interview. He writes, “My mother is driving me through the rain to the beach…The rain is thorough and silvery. We do not speak. The trees along the road are scrubby and gnarled and assaulted by reeds. I am huddled in my jacket. No one else is on the road. You never thank your mother enough. The road is so wet…” Here, he interjects in the middle of the sentence—you can never thank your mother enough—with an unexpected truism and we nod our head in agreement, accepting the interruption. In fact, loving the outburst. Doyle’s endings are also seamless. In the same essay, “…we drove home through the ranks of the bent twisted little trees. There were pitch pines and salt cedars, and here and there beach plums, and thickets of sumac, and I thought I saw a tangle of bearberry but I could not be sure.” A perfect rhythm, an ordinary list, but a calm moment to end a simple essay about the ways we love and appreciate our mothers.

This book is a gift. After a year of uncertainty and turmoil, we can all find a little grace in Doyle’s words, and even more so now that Doyle is gone. We can savor these small memoirs, return to them for the Doyle wisdom as we need them, especially as we circumnavigate the difficulties of humanity, but also the beauty of people and the goodness we have to offer. And that’s the contribution that Doyle imparts in his beautiful book: splendor. When I witness some tiny thing on my farm, whether the light has just warmed the icy grass or my daughter comes running toward me from the barn with a dead bird in her hands, I’ll think of Doyle and his wisdom: “The things that we remember the best, the things that matter the most to us when we remember them, are the slightest things, by the measurement of the world; but they are not slight at all. They are so huge and crucial and holy that we do not yet have words big enough to fit them.”

___

Melissa Matthewson lives and writes in the Applegate Valley of southwestern Oregon. Her essays have appeared in Guernica, Mid-American Review, River Teeth, Bellingham Review, and Sweet among others. She teaches writing and literature at Southern Oregon University and runs an organic vegetable farm.

3 comments

sarah m says:

Feb 14, 2018

I miss him terribly, but his books will speak for him… forever.

Troy says:

Feb 17, 2018

Thank you, Melissa, I just started reading this book a few days ago and think to myself, I wish I could only be half as wonderful in my life and writing as Brian was. Thank you for the review. – Troy

Carol Tyx says:

Mar 5, 2018

I’m going to go right out and get this book. You reminded me how much I love Doyle’s work and I was mourning there were no more Brian Doyle books. Thanks you for such a lovely review.