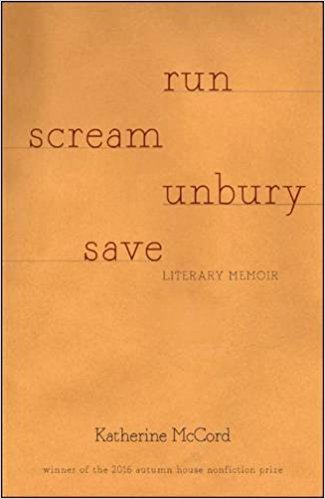

Katherine McCord’s book Run Scream Unbury Save, winner of the 2016 Autumn House nonfiction prize chosen by Michael Martone, is a whetstone of a fragmented and poetic memoir in bursts and paragraphs. You will emerge from each page emboldened to capture the exact this-ness of your day as a shadowbox-diorama with that exact plastic dinosaur and this exact wad of sponge for trees you colored insufficiently with a green marker (remember?). McCord’s work is “stream of consciousness,” but not a cup of tepid pondwater of raw free-writes or the journal stuff of “why am I sad today?” That stream is not the first pass but the final barrel-roll through the linebackers of an extended sports metaphor that flails like a wipeout on an icy sidewalk because what do I know about football anyway? McCord’s layered entries glance off narrative threads having to do with her family, crafting, her sister, texting, wasps, writing, the CIA, seasonal affective disorder, dreaming in horses, and teaching, among a million other things. The binding material here is a voice that flutters like a bird-heart, hurtling the gaze of the reader through the sky and dropping all pretense of packaged experience, opting instead for revelatory and intimate association.

Katherine McCord’s book Run Scream Unbury Save, winner of the 2016 Autumn House nonfiction prize chosen by Michael Martone, is a whetstone of a fragmented and poetic memoir in bursts and paragraphs. You will emerge from each page emboldened to capture the exact this-ness of your day as a shadowbox-diorama with that exact plastic dinosaur and this exact wad of sponge for trees you colored insufficiently with a green marker (remember?). McCord’s work is “stream of consciousness,” but not a cup of tepid pondwater of raw free-writes or the journal stuff of “why am I sad today?” That stream is not the first pass but the final barrel-roll through the linebackers of an extended sports metaphor that flails like a wipeout on an icy sidewalk because what do I know about football anyway? McCord’s layered entries glance off narrative threads having to do with her family, crafting, her sister, texting, wasps, writing, the CIA, seasonal affective disorder, dreaming in horses, and teaching, among a million other things. The binding material here is a voice that flutters like a bird-heart, hurtling the gaze of the reader through the sky and dropping all pretense of packaged experience, opting instead for revelatory and intimate association.

Stream of consciousness as a phrase (William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890, thx Google) was first used in a literary sense to describe the work of Marcel Proust, James Joyce (i.e. in Ulysses) and the work of Virginia Woolf (see The Waves for some awesomeness). Stream of consciousness reconstructs with careful attention and precision the feeling of thought with all its bright sparks and twists and rapidity. In contrast, my typical journal entry starts like this: “I’m feeling shitty and I’m not sure why,” (though it’s always vague catastrophes impending that I am sure I can predict) followed by an attempt to talk myself down from whatever current fear I’ve got whipped up into a healthy meringue. But the “meringue” in that last sentence—I wouldn’t journal with that word; that’s me talking to you, not me talking only to me. Beyond the sinkhole of my journal, the associations captured by stream of consciousness present a portrait of a moment and a mind. What I don’t write in my journal is this: These days I’m afraid because Trump just announced an increase of troops into Afghanistan. And that country—never been there—makes me think about the Soviet invasion of as reflected through the 1980s in Mr. Joe Miller’s history class (cinder-block painted in so many layers of yellow that it had started to look over the years like glossy cheese). The 1980s were also about fears, and the cassette “Songs from the Big Chair” from the band Tears for Fears, waiting for the bomb with every day being the day before the day after, and I felt like maybe those dark-eyed men wearing tons of hair gel understood. But what Big Chair? I could wonder about it for hours as if knowing which chair would keep us alive. What kept us alive in the era of the Big Chair was dumb luck, I assume, plus not having an erratic tyrant in charge with a hair like an orange meringue. (Too much? Or not enough? If I apologize, my dead socialist relatives will unbury themselves, run/scream/buy plane tickets, reconstruct their own skeletons to ship their German skulls over the ocean just to look me in the eye with their eye sockets and ask, “Too much?”)

There is something in the details that will save us in the face of the vague and imprecise erasure of the world. Details—like a horse trough somehow painted with glitter that McCord’s daughter uses to store her clothes in—offer the solace of the particular and the real. McCord’s details dredge this “stream of consciousness” that pursues its own fluid self with avid reckless attention, steering always away from abstraction and vagueness of emotion toward the shocking vivid precision of remembered sights, sounds, smells, slants of light, feelings, and street corners. McCord’s short entries string together, given a sense of propulsion precisely by her own breathless quest for honesty, confiding in the reader that she can’t quite find the thing she means to say and so she returns on each page with another angle, refracting and pursuing the quickening edge of life and consciousness itself.

__

Sonya Huber’s newest book is Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System. She teaches at Fairfield University, where she directs the low-residency MFA program.