In the fall of 2005, my thirteen-year-old son tried to hang himself by using a leather belt that held up the pants of his Easter suit. By some miracle, the belt ripped in two, throwing my son to the floor, leaving him breathless but alive.

In the fall of 2005, my thirteen-year-old son tried to hang himself by using a leather belt that held up the pants of his Easter suit. By some miracle, the belt ripped in two, throwing my son to the floor, leaving him breathless but alive.

Since then, I’ve come to see death and life separated by a thin, quivering line. One minute you’re standing at the stove, cooking spaghetti for your family, picturing them laughing and talking around mouthfuls of Italian bread. The next, you’re racing to the emergency room, angry with yourself for minimizing your son’s depression.

I’ve learned as well that mother-son relationships are complicated. What’s more, wherever there’s love, there’s bound to be some pain too.

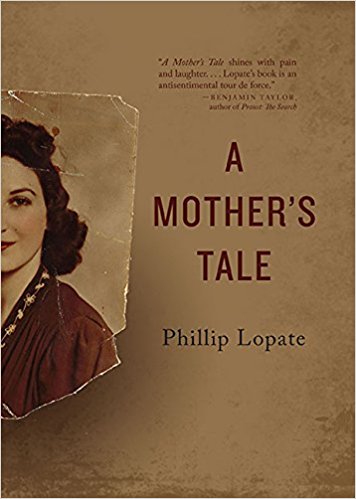

In part, this is what Phillip Lopate addresses in his slim new book A Mother’s Tale. He possesses a deep love and respect for his mother, Fran Lopate. But she’s a hard woman to love—jealous, narcissistic, and needy.

In 1984, Lopate conducted a series of taped interviews with her, which became sort of a stage for his mother on which she tells her life story of being orphaned at age eleven, raised by sisters who didn’t want her, trapped in a loveless marriage, and then bound to a life of domestic drudgery. All this prevented her from pursuing what she perceived as her true calling: the theater. (At age fifty, though, she launched a somewhat successful acting and singing career, and might be remembered from the iconic Alka Seltzer commercial, “Mama Mia, That’s a Spicy Meatball!”)

After the interviews, Lopate put the tapes away and didn’t play them for thirty years.

On the tape, Fran Lopate tells us, “I had a modicum of talent. I wanted to do something more with my life…. It seems that when I was younger, every time I tried something I was ridiculed. I was put down. Nothing I did was ever good enough.”

After hearing this, Lopate says, “…she had been frustrated at every turn: thwarted, thwarted, thwarted. Well, she certainly was thwarted, so why do I feel like mocking this assertion? I guess because it doesn’t take into account that it was she who dropped out of high school, she who chose to obey her sister, she who opted to marry my father, and not pursue her dream, etc., etc.”

A master of voice, Lopate plays two key parts in this book. He’s the in-the-moment, younger interviewer, who’s debating with his mother, challenging her “truth.” Interceding is the older Lopate, who’s less judgmental and more reflective.

The climax occurs when the younger Lopate and his mother argue about his suicide attempt. “Any time a mother sees a son in a state like that, unless she’s crazy, is going to feel guilty,” says the mother. “And I felt guilty. There’s nothing I could do to help you.”

In the next breath, however, she scolds him for not calling sooner, not letting her know until the next day that he was in the hospital.

“Well, I was in a coma—“

Lopate doesn’t reveal much more about this. Instead we hear the mother blame him for being distant—not reaching out, not calling regularly, not sharing his problems.

“I don’t understand how I could have come to you with my problems when you always had seemed so troubled to me,” replies Lopate on the tape. “Even when I was young, you had come to me with your problems….”

In fact, the mother confided in him, as if he were one of her girlfriends, about her various affairs, abortions, and immense disdain of his father.

Obviously Fran Lopate was not the perfect mother, but then again, who is? Children often come (especially during her time) when they’re young, naïve, and selfishly craving freedom and adventure.

“Listening to these tapes impressed upon me how often even an intelligent person can fail to observe the truth about herself,” says Lopate, who after three decades returns to the tapes less reactionary, softer, and more forgiving. This combination of voices and perspectives provides a more resonant truth about family dynamics and more importantly the tenuous and curiously malleable nature of love.

__

Debbie Hagan is the mother of two practically grown sons who recall being forced into wearing tortuous bow ties and suits for every holiday. In addition to writing and editing book reviews for Brevity, she writes for Hyperallergic and her essays have been published in Pleiades, Superstition Review, Don’t Take Pictures, Brain, Child, Boston Globe Magazine, Dime Story, and elsewhere. She is also a visiting lecturer at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.