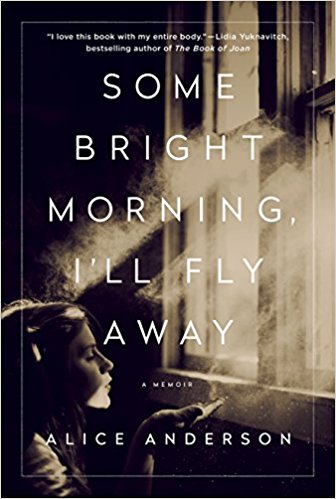

Some Bright Morning I’ll Fly Away, by Alice Anderson, is not only a telling of a battered woman’s storm-ravaged life, it’s also a story of redemption, resilience, survival, and a reclamation of one’s true self in face of one trauma after another. The cascade of events begins with her father, whose sexual abuse of his four-year-old daughter continues through her school age years. Just as she finds her “soul-deep” place while in college, Anderson is thrown airborne from her scooter by a rogue car. She sustains critical injuries, her long recovery whiplashed by endless setbacks, convincing her to drop out of college. At her mother’s urging, Anderson attempts to re-fashion herself into a model in Paris. But six months later she’s had enough, and returns to school. Her life is blown sideways once again when Hurricane Katrina blasts through Mississippi, where she lives in an upscale neighborhood with her physician husband, Liam, and their “sweet three,” as she so tenderly refers to her children. Their home was the only one remaining intact, missed by what Anderson describes as “the wrath of the twister.”

Some Bright Morning I’ll Fly Away, by Alice Anderson, is not only a telling of a battered woman’s storm-ravaged life, it’s also a story of redemption, resilience, survival, and a reclamation of one’s true self in face of one trauma after another. The cascade of events begins with her father, whose sexual abuse of his four-year-old daughter continues through her school age years. Just as she finds her “soul-deep” place while in college, Anderson is thrown airborne from her scooter by a rogue car. She sustains critical injuries, her long recovery whiplashed by endless setbacks, convincing her to drop out of college. At her mother’s urging, Anderson attempts to re-fashion herself into a model in Paris. But six months later she’s had enough, and returns to school. Her life is blown sideways once again when Hurricane Katrina blasts through Mississippi, where she lives in an upscale neighborhood with her physician husband, Liam, and their “sweet three,” as she so tenderly refers to her children. Their home was the only one remaining intact, missed by what Anderson describes as “the wrath of the twister.”

But the most epic flood of all is just beginning. In the wake of Katrina, Liam’s OCD and alcoholism spirals out of control, reaching its high-water mark when he attacks Anderson at knifepoint. To protect her life, and the lives of her children, she finds refuge in a FEMA trailer far from Liam’s fury. For her children’s welfare, for self-preservation, she walks straight into the ensuing wind-whipping legal battles, holds her own in face of a misguided social service system, and powers ahead despite her fearmongering husband, who has threatened to take their children from her and to have her locked up in a psychiatric ward. Scariest of all, is Liam’s Plan B threat: “I’ll kill you. Without a second thought.”

Anderson’s moment-by-moment detailing of her husband’s violence, the kind seen in psychological thrillers, drove me to question why I couldn’t, wouldn’t, seek shelter from the book, why I continued reading, page after page, late into the night and, yes, even while out for a walk.

I was committed to the book because I have a personal interest in traumatic memoirs of this nature. In the memoir I’m currently completing, I write about the personal trauma I experienced when an older driver confused the gas pedal for the brake and mowed down dozens of us at a farmers’ market fourteen years ago. The book, which is about how I take back my life after sustaining severe physical and emotional injuries, is not always uplifting. And there are stories of how the crash affected others: survivors, the dead, the driver himself. Brighter moments do lend meaning to the narrative: finding consummate love for instance. But it took me a long time to figure how to paint the page with such levity. As perverse as it is, people have a morbid curiosity for the tragic; I assumed my readers would possess the same macabre inclination. But I quickly learned, after reading lots of memoirs, and receiving feedback from editors and writing mentors, that levity is essential to traumatic narratives. Buoyancy gives us space to breath, to re-align ourselves, offering us enough emotional reserve to keep reading.

So how does Anderson do it, deliver disaster relief among all wreckage? A stellar, award-winning poet, she sings from the page with intoxicating beauty. When referring to her children, she writes, “Sweet three attached like sequins.” Later, she notes how they “smell like starlight and sugar cookies and sing like birds filling blue skies.” And while in court, her friends and family on her side, we are on her side, afraid with her as she describes her interior world, “I was moving through fog akin to shifted night sugar.”

More than her poetic finesse, Anderson’s humor is priceless, the way she rouses laughter with her Mississippi dialect: “Doesn’t that seem a little … down the bayou of batshit crazy?” she asks when another model tells Anderson the owner of the agency for which they work is a big-wig oil trader.

There’s no arguing that Anderson endures untold devastation equal in destruction to Hurricane Katrina. Yet, from deep within the wreckage, she digs up the remaining scraps of her broken life and, piece-by-splintered-piece, recycles them into “dazzling scaffolding”—a gift really, one she leaves for us to unwrap in the very first sentence of the prologue: “We make chapels of our scars.”

__

Melissa Cronin is a freelance journalist and author. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Washington Post, The Jerusalem Post, Narratively Magazine, Saranac Review, River Teeth Journal, Under the Gum Tree, and Intima. She is currently completing a memoir. Melissa holds a BS in Nursing from Boston University and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts.