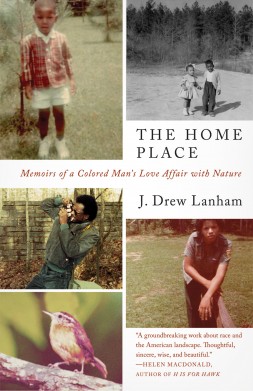

“There are still priceless places,” J. Drew Lanham says, “where nature hangs on by tooth, talon, and tendril.” And there remain rare breeds of humans who fall in love with a land darkened by the blood and sweat of ancestors purchased to work it.

Google a list of nature writers and a band of such similar skin tones scrolls across the screen you might be viewing a steadily receding ice cap. I recognized the bias reading Thoreau, Muir, Abbey, Wilson, Dillard, etc. but did not probe the roots of that particular privilege, which itself suggests privilege. My love of nature stems from growing up on a farm that has been in my family for at least six generations, so I hadn’t appreciated before reading The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature that legacy could also dissuade a sense of connection. “Conservation is simply a longer word for care,” Lanham says in an interview, but our ability to care corresponds with hope of seeing our affection requited. For many in the South, where Lanham grew up and still lives, “thousands of people can’t afford a square foot of the soil that their ancestors paid for with their lives.”

This love affair with nature is a complex one, addressed to an audience accustomed to misinformation and wary of idyllic depictions, but also in need of new models of care particularly from brown and black folks like his father. A teacher, as is Lanham’s mother, James Hoover Lanham farmed their seven acres in Edgefield, South Carolina, in his spare time to feed their family and supplement their income. Like many men of his generation, “Big Chief” expressed love more often through toil than touch. Clearing brush and stream, fixing fence and roof, his hard labor brightened the blood and filled the lungs of their home place. Young Drew watched his broad-shouldered exemplar “in bone-shivering awe as he worked through the discomfort of wet and cold without complaint.” A dimensional character as likely to recite the epic poem Beowulf as point out geological specimens of feldspar, mica, and quartz, Hoover clearly influences Lanham toward his career as an ornithologist, wildlife ecologist, and professor at Clemson University.

But his widowed grandmother, Mamatha, may be what makes Lanham the scientist he is—capable not only of publishing in peer-reviewed research journals but also of being moved by “the perfume of place: the pleasant mustiness of decaying leaves on a Blue Ridge forest floor, the sulfur stink of a Beaufort mudflat at low tide, the drunken sweetness of an orchard in October.”

Sent at age four to provide Mamatha with company in her ramshackle behind their family’s house, young Lanham grew up in her “tin-roofed, broomstraw-swept, rusting, rural, wood-fired world.” Born in 1896—one generation removed from slavery—Mamatha, “straddled nine decades and all of the history and social evolution that came along with them.” The perfect narrative device for bringing to life the cultural landscape that fledged a black birder, her character helps illustrate his unlikely calling. Plus, with her religious superstitions and knowledge of medicinal herbs, she is a fascinating personality, “a conjurer with a foot in two dimensions—this world and the spirit one.”

Lanham finds more canonical models at school, including Aldo Leopold. Fans of Sand County Almanac will appreciate its influence on Lanham’s descriptive prose:

Loblolly is a fast grower that stretches tall and mostly straight in forests that have been touched occasionally by fire and saw. In open stands, where the widely spaced trees can grow with broom sedge and Indian grass waving underneath, bobwhite quail, Bachman’s sparrows, and a bevy of other wildlife to call home. But where flames and forestry have been excluded, spindly trees fight with one another for sun and soil and will grow thick like the hair on a dog’s back.

But giving voice to place is particularly important to those who have long been dispossessed, Lanham says, since it yields a critical sense of self-purpose and belonging.

Through his observations of loblollies and church sermons, vireos and southerners, Lanham provides another model, harvesting affection for a place that is not always receptive to it. His writing style fosters integration by drawing together the narratives of slavery and conservation and the languages of science and literature. The Home Place thus supports a promising shift in an age-old dialogue increasingly aware of diversity’s role in propagating holistic communities and resilient ecosystems.

___

Amy Wright is the author of the poetry collections Everything in the Universe, and Cracker Sonnets, as well as five chapbooks, including the prose collection Wherever the Land Is. With William Wright she co-authored Creeks of the Upper South, a lyric reflection on the connection between waterways and cultural habitats.