I had the privilege of being edited by Richard Todd. It was my MFA manuscript for Goucher College, and to give you a sense of how massive that stack of paper was, it cost Todd $6.35 to mail the manuscript priority mail to my house. It weighed more than a Chihuahua.

I had the privilege of being edited by Richard Todd. It was my MFA manuscript for Goucher College, and to give you a sense of how massive that stack of paper was, it cost Todd $6.35 to mail the manuscript priority mail to my house. It weighed more than a Chihuahua.

Stuck to this Leviathan are dozens of Post-It notes scratched by Todd’s black ink. I wrote the word “flabbergasted” into the manuscript, as in “When I told people I was working on a horse racing project the first question anyone would ask me was, ‘Oh, do you ride?’ I would always say, nope, never. They would look flabbergasted ….” Todd wrote in the margin “Too much?” Of course it was too much.

Six paragraphs later, I wrote trees were “swollen with leaves.” “Too much?” Of course it was too much.

There were dozens of questions that weren’t questions, just his Toddsian way of saying “Change this.” And you change because, really, who are you?

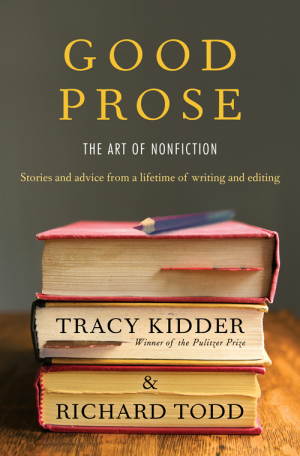

And in these notes I felt, if only for an instant, like I was the young Tracy Kidder portrayed in Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction (Random House, 2013,) a green reporter clawing at the wall for anything resembling a toe-hold in publishing, a young writer who an editor might also say, as the Atlantic’s Bob Manning once said of Kidder, “Let’s face it, this fellow can’t write.” But write on Kidder did.

Good Prose validates writing as collaboration, or, writing as team sport. The pairing is every bit the battery at the bottom of today’s baseball box score. The catcher calls the signals—suggestions—as to how to approach the batter. The pitcher can shake off the pitch, go with whatever he feels might be a better approach to hurl toward home plate. I picture Todd in a crouch behind home plate putting down two fingers for a curve ball, “A curve would work here, no?” Of course a curve ball would work here.

The pitcher delivers. It works. The pitcher gets the credit. And any good pitcher knows he’s only as good as his catcher. In the “book” of pitcher, you better believe he thanks the catcher in his acknowledgements.

Good Prose, by its very nature, illustrates the forty-year fellowship between Todd and Kidder. And for those who have read nearly all of Kidder’s work (Namely Mountains Beyond Mountains, Strength in What Remains, Among Schoolchildren, House, and My Detachment), the italicized chapter introductions offer wonderful looks under the hood to see the mechanics of the work, the back and forth, wins and losses, false starts and engine failures.

At the beginning of the section titled “The Problem of Style,” Todd writes, “H.W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage belongs on every writer’s shelf, and there it was on mine, but the book became a real presence in my life only when William Whitworth took over as the eleventh editor of the Atlantic Monthly. … His comments often concerned subtle grammatical violations, and after noting one, such as ‘a possessive can’t be an antecedent,’ he might add, ‘See Fowler.’ ‘See Fowler’ became a popular sotto voce mutter among the temporarily traumatized staff.”

Good Prose belongs on the short list in the pantheon of writing books—or books writers use to put off writing—certainly on the top shelf of every narrative nonfiction writer. And if I became the editor of a magazine, I’d write in the margins to prose needing goodness, “See Good Prose.”

And what a treat, Richard Todd and Tracy Kidder were at AWP in March for a panel to talk about Good Prose and nonfiction writing. Afterwards, Kidder signed my copy of Good Prose, “To Brenda.” I viewed it like those valuable baseball cards that have an error. I moved down the line and stood across from Todd and he looked at what Kidder had signed and looked back up at me, and back down to “Brenda.”

“May I?” he asked and laughed.

“You’re the editor!” I said.

He laughed some more, added the ‘n’ to the end of my name and initialed it R.T., always the editor.

—

Brendan O’Meara is a freelance reporter and author of Six Weeks in Saratoga: How Three-Year-Old Filly Rachel Alexandra Beat the Boys and Became Horse of the Year. He’s also the host of the podcast Hashtag #CNF, a conversation about reading and writing with authors in the genre of creative nonfiction. Follow him on Twitter @BrendanOMeara.

5 comments

Ryder S. Ziebarth says:

May 17, 2013

Love this! I was in that line.

Brendan O'Meara says:

May 20, 2013

Hey, Ryder, thanks for the kind words. It was a great talk at AWP, wasn’t it?

Earl Swift says:

May 27, 2013

Nice job, Brendan!

Brendan O'Meara says:

Jun 12, 2013

Thanks, Earl!

My Top Writing Books says:

Jun 4, 2014

[…] Good Prose by Tracy Kidder and Richard Todd is a wonderful collaborative book between a writer/editor tandem. I reviewed it here. […]