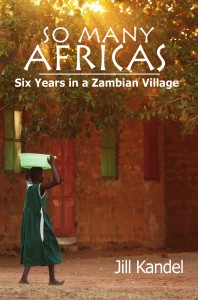

I “met” Jill Kandel in 2006 when she submitted a wonderful essay to Relief Journal, where I was the editor for creative nonfiction. We published that essay, and over the next few years I was not surprised to see Jill publish work in impressive journals, including The Missouri Review, Gettysburg Review, River Teeth, Image, Pinch, and Brevity. The road from writing essays to crafting a memoir is a long one, and last summer Jill learned that her long years of writing and compiling and revising and then writing some more had finally resulted in a book contract: her book was selected for the 2014 Autumn House Nonfiction Prize. So Many Africas: Six Years in a Zambian Village is lyric and surprising—a gorgeous first book. Shortly before the book released on January 1, 2015, I asked Jill to share a little about her process.

I “met” Jill Kandel in 2006 when she submitted a wonderful essay to Relief Journal, where I was the editor for creative nonfiction. We published that essay, and over the next few years I was not surprised to see Jill publish work in impressive journals, including The Missouri Review, Gettysburg Review, River Teeth, Image, Pinch, and Brevity. The road from writing essays to crafting a memoir is a long one, and last summer Jill learned that her long years of writing and compiling and revising and then writing some more had finally resulted in a book contract: her book was selected for the 2014 Autumn House Nonfiction Prize. So Many Africas: Six Years in a Zambian Village is lyric and surprising—a gorgeous first book. Shortly before the book released on January 1, 2015, I asked Jill to share a little about her process.

—

Lisa Ohlen Harris: Like so many of us, you started writing in your forties. Tell me a little about how you got started.

Jill Kandel: I started writing at age forty-one because I had a son who couldn’t read. He had severe learning disabilities and by the age of ten, he was embarrassed at all The Cat and the Hat books he was struggling through. He called them “baby books.” So I began to write stories for him. I knew every word and syllable and vowel combination that he could or could not read. I joined a writing club and one of the writers said he’d like to hear more about my life in Africa. He challenged me to write about it. I was homeschooling my four children at the time. So I’d get up at 5 a.m. and write till 9 when the school day started. I wrote six days a week, four hours a day. Early mornings was my only alone time. I’d wake up, drink coffee, and write.

LOH: You write about some difficult years in your marriage. How did your husband respond?

JK: I didn’t let anyone read or see my writing until I had written what I needed to write. After that, I’d let my husband read it. He is from the Netherlands and English is his second language. So sometimes he didn’t really get the nuances of my meaning. Sometimes he wanted me to just let it go. I wrote about some painful events and there was a lot of tension at times. In the end, we came to an understanding. He doesn’t censor my work, but I give him space for input. He’s very supportive of my writing. I didn’t want So Many Africas to be a “kiss and tell” sort of ugly memoir. I want to protect and honor my family. I live with them! I like them. As a writer you hold people in your hand. I want to honor that. I have found that there are kind ways to tell hard stories.

LOH: Have you experienced writer’s block?

JK: I’ve only had writer’s block once in my life. I attended a weeklong writing workshop, and my teacher basically said my writing was crap. I couldn’t write after that for three long months. Every day I sat down at my computer her words circled my head. I had a copy of her memoir (which I loved) and I got up one morning and threw that book across the room. Then I sat down and started writing again. Anger kickstarted my writing. I knew she was wrong. I knew I had something to say and that I could learn how to say it well. Later, I learned that she had been sick that week and was suffering from severe back pain. I suppose that played into her response to my work. But people will tell you things. And you have to decide if you are going to believe in others or if you are going to believe in yourself and your words. I’ve been to many workshops over the years. So I had one bad one. One out of seven or eight, that isn’t bad odds. Get up. Move on. Throw a book if you have to.

LOH: You were quite isolated during your six years in Zambia. Did you realize in advance how hard this life would be?

JK: I had no idea. It was all rather exotic and exciting. I was a newlywed. I’d worked for three months in Japan and three months in Zambia as a student and then as a nurse. I thought living in a village would be a cinch. I was young and naïve. My husband loved Zambia and had a dream job, but we were really foreigners to each other. I didn’t understand his culture any more than he understood mine. So we came into a new marriage and a new job and moved three thousand miles away from my family. For most of our six years in Zambia, there was no phone or Internet. It was a ten-hour canoe ride to the nearest town. How can anyone be prepared for that kind of isolation? For the first nine months we lived in Zambia, we didn’t have a house—just a room in a hotel. I was overwhelmed with culture shock, survival, finding food, cooking, washing, disease.

LOH: Did you ever think about leaving Africa (or your marriage)?

JK: I’ve never been one to throw in the towel. We were committed. But we made mistakes and built a lot of bad habits into our life. It wasn’t till years later that we were able to find reconciliation and peace about the first six years of our marriage. And a lot of that came through the writing, and the discussions the writing led to.

LOH: I find it amazing that you gave birth to your first child in that remote setting. And you’re a nurse. Weren’t you haunted by thoughts of all that could go wrong? Why did you want to give birth in that remote location?

JK: I was so exhausted by that time that it was just plain easier to stay. There weren’t a lot of choices. Going back to my parent’s home would have required traveling months ahead of time and I didn’t really want to be seven months pregnant and living with my parents. We had two new Dutch doctors in Kalabo Village at the time and there was a government hospital. I trusted the doctors would do fine.

LOH: In your book trailer, you say So Many Africas is the story of losing yourself and silencing your own voice. Would you share a little more?

JK: There were five languages spoken in Kalabo District: SiLozi, Luvale, Nyengo, Mbunda, and Nkoya. I couldn’t tell the five of them apart. Words have always been a very important part of my life and I was living in a village where the act of talking and communicating was a daily struggle. When you lose the ability to communicate with those living around you—really communicate—there is a sense of loss and isolation. And something odd happens: when you stop talking, you stop hearing yourself, too. You forget who you are. I wanted to be a good wife. I wanted to encourage my husband. So I didn’t talk about what it was really like for me.

LOH: And yet this memoir overflows with you, with the beauty and severity of your life in Africa, and with your own passionate voice.

JK: When we moved back to America, my husband loved talking about Zambia and telling stories. I didn’t. I wanted to forget. But I needed to go back to the memories. I needed to find the words in order to understand the years. When I started writing about Africa, what I was doing was putting words into that time which was basically a big silence in my life. I was allowing myself to say what I hadn’t said. It was lonely. It was difficult. There was beauty, too. I needed to articulate both the grief and the glory. I needed to take away the silence.

__

Lisa Ohlen Harris teaches advanced memoir and essay writing online for Creative Nonfiction. She is the author of The Fifth Season: A Daughter-in-Law’s Memoir of Caregiving and the Middle East memoir Through the Veil. The Fifth Season was recently announced as a 2015 Oregon Book Awards finalist in creative nonfiction.

2 comments

Jill Kandel | Q&A Book Review says:

Jan 29, 2015

[…] first Q&A up online today! Give it a gander to read about Throwing Books & Writer’s Block and […]

Jill Kandel | Initiation Rites says:

Mar 10, 2015

[…] After that GREAT book party with appox. 125 people in attendance, after the fun AW cover story, after the good reviews at Collegeville and Brevity. […]