When I was first introduced to the creative essay, I was gobsmacked. An essay provides the perfect vehicle to explore the self while prying open the larger world. I’ve used the form to wonder and wander my way through topics as wide-ranging as class and gender ever since. It was a match made in genre-heaven. Until, a couple years ago when, for no apparent reason, I returned to my childhood church.

My attachment to Corpus Christi in Rochester, New York, made no sense. I tried wrestling with it on the page but the topic was so baffling, ordinary essaying no longer worked. The more my questions became situated outside my comfort zone, the more the writing needed to follow suit. Essay-as-question bloomed into essay-as-quest.

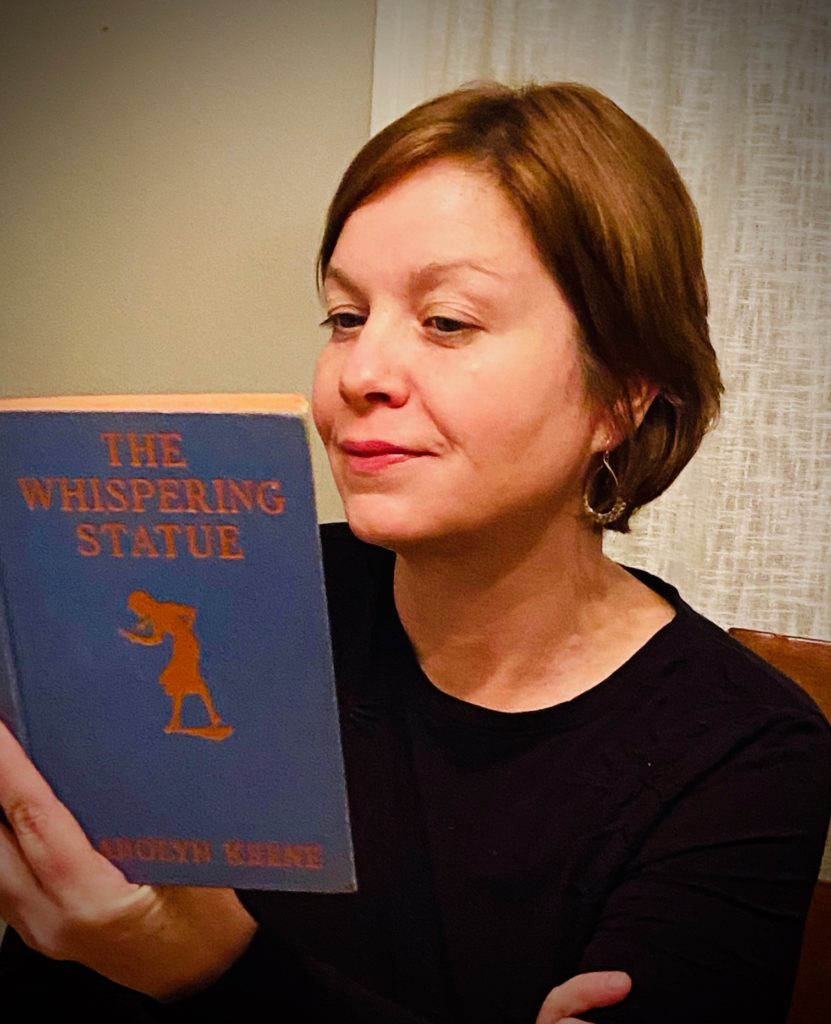

Which is to say that one day while staring into my laptop, I found Nancy Drew looking back. What could I do but follow her lead? I’d always used writing to help solve mysteries. Now I began to add more dynamic investigative elements to my work.

Here’s how you can Nancy Drew your essays, too.

Locate the Body

Just as good mysteries begin with a body, so does an essay. I don’t mean a corpse—though that is an option. Like Nancy’s mysteries, where a gang of fur thieves in Vermont is about as dicey as things get, the bodies populating essays tend to be surprisingly low-key. It might be the aunt who reads horoscopes at the breakfast table, for instance, or the red silk dress you longed to wear to prom. The more specific the body, the better. You don’t need to understand why you’ve glommed onto the horoscope-reading aunt—perhaps it’s better if you don’t—you only need a repository for your questions. The body provides a trap for the wild animal of your imagination—it’s the thing that’s more than a thing, though it must also stand for itself.

A body works best when it organically arises. When I noticed a Virgin Mary statue had gone missing from my church, for instance, I was curious. Curiosity bloomed into obsession. Eventually, I launched a full-blown search. The missing statue became the shape my longing took. She provided a stand-in for questions about devotion and a concrete focus for my quest—a slightly wonky quest perhaps, but what quest ever makes sense?

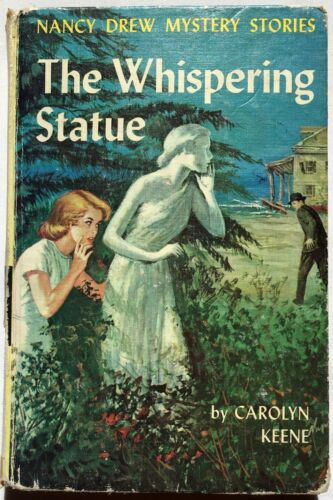

And actually, I was in good company. In The Whispering Statue, Nancy also searches for a statue. Sculpted from Italian marble, Nancy’s statue was said to whisper to visitors at her seaside mansion. My statue was cast in plaster and from a working-class church in Rochester, but, like Nancy’s, had the rare ability to speak.

“Find me,” she whispered.

What could I do but try?

Pack your Bags

As a kid, I read Nancy Drew for her sleuthing and endless supply of dresses, but also for the reason many of us read—to travel beyond the spaces in which I was so firmly lodged. Nancy ventured to tropical islands and snow-covered slopes. She sleuthed in swanky city apartments, charming farmhouses, and lakeside bungalows. She boarded buses and trains and airplanes and solved mysteries all over the world.

I felt a bit like Nancy as I drove through the Atchafalaya Basin. I was writing about the fading sacrament of Confession and, after mining statistics and memory, I still wasn’t satisfied. So I traveled to Cajun Country to meet a priest who’d converted an old ambulance into a mobile confessional booth. Father Champagne parked his confessional outside health clubs and Mardi Gras celebrations and waited for penitents to arrive. Like the missing statue, the mobile confessional offered a unique and tangible touchpoint to meaningfully engage with the abstractions that had snagged me.

Embrace the Three Cs: Chaos, Curiosity and Confusion

An orderly world might be heaven in your child’s bedroom or at the dried fruit section of Trader Joe’s, but tidiness is the essay’s kryptonite. The essay thrives on chaos. Curiosity is its basic fuel. Confusion is its sweet spot.

Like Nancy, who undertakes multiple mysteries in one book, an essay often tempts us with seemingly disparate threads. “You’ve really lost it this time,” I said as I moved from statue-hunting to researching relics and holy water. Even when I began to write my essays, dark clouds of doubt hung overhead.

Why this topic? Why me? Why now?

If I’d waited until everything made sense, I’d still be frozen at my keyboard. In essays, as in mysteries, strands of confusion and obsession always come together in the end. Everything is related. The hardest work of writing is remembering this.

Practice the Fine Art of Snooping

Nancy Drew knows which fork to use for seafood and which for salad. An expert flower arranger, she can also ski and waltz and skate. She’s the perfect girl, really—minus her tiny propensity to break and enter. Nancy hides in closets, rifles through desk drawers and even dons disguises. In other words, Miss Nancy is a bona fide snoop. After a swift but thorough cost-benefit analysis concerning the ethics of her actions, Nancy forges ahead. We must do this too. Not break and enter so much as doggedly pursue our obsessions.

Go one step further than your comfort zone, someone recently advised me. That’s where the prize is. It’s good but tough advice, as true in writing as in life. A literary expedition requires stepping out of your comfort zone. It involves bothering strangers, exploring new spaces, and learning to trust your gut.

In The Whispering Statue, Nancy unearths a statue in a garden shed, but as she clears away the cobwebs she becomes convinced it’s a fake, yet there’s no evidence to support her view. It would have been easiest for Nancy to drop the matter and return to the sailboat races, which, though she hails from a landlocked place, she’d dominated in an earlier chapter. Instead, Nancy keeps looking until she finds what she’s truly seeking.

The point is this: Nancy Drew honors her hunches 100 percent of the time. When I started looking for my statue, I discovered her twin on eBay. I could have stopped searching and looked to the eBay Virgin for whatever answers I sought, but an essayist, like a detective, is after the real deal, and will not be satisfied by anything less than genuine discovery.

Be Brave or, If All Else Fails, Stay the Course

Haunted Inns? Rattling windows? Creaking staircases? Nancy is halfway to the attic while everyone else’s eyes are popping as they wonder what to do. In an era of calling out privilege, I have to acknowledge that the teen detective has innumerable resources: a shiny roadster, a housekeeper, and an apparently unlimited travel budget, but, in fact, confidence is her most essential asset.

The antidote to fear is action. No matter how plagued Nancy is by distractions or doubt, she walks headlong into the unknown. Doesn’t this sound familiar?

The bravest people I know are seated right now at desks or kitchen tables, laying down words with precision and care, not knowing how (or even if) their sentences will land in the larger world. To write anything at all is to accept the tension of not knowing and proceed anyway. The best writers don’t dismiss doubts but withstand them, letting curiosity and intuition become flashlights leading them through dark corridors.

Just like Nancy would do.

___

Sonja Livingston’s latest book, The Virgin of Prince Street, uses an unexpected return to her childhood church as an occasion to travel through space and time to explore the changes in the larger Church and in her own life. The result is a generous but unflinching look at the rapidly shifting nature of devotion. Sonja’s first book, Ghostbread, won an AWP Book Prize for Nonfiction and has been widely adopted for classroom use. The author of four books, her writing has been honored with a NYFA Fellowship, an Iowa Review Award, a VanderMey Nonfiction Prize, an Arts & Letters Essay Prize, and grants from Vermont Studio Center and The Deming Fund for Women, and appears widely in anthologies and outlets such as Salon, Creative Nonfiction and LitHub. Sonja is an associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and teaches in the Postgraduate Program at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

5 comments

Nina Gaby says:

Jan 21, 2020

Perfect frame for essaying! My childhood heroine and my fascination as a Jewish Rochestarian for Corpus Christi church. I fear I will have to break my vow of abstinence and buy this book.

Elizabeth Gaucher says:

Jan 21, 2020

Have mercy, YES. All the YES. It’s those weird images that won’t fade, the tug inside that keeps telling you something either is or will lead to a key to the perceived but unknown. Thank you!

John Russell says:

Apr 13, 2020

Thank you for helping me to remember some things about my nature and my early education. I read all the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew novels. Reading your work gobsmacked me back to being like a kid again.

Anna Redsand says:

Jul 24, 2020

The antidote to fear is action. I needed to read that today.

Kiran Kher says:

Sep 26, 2021

Have mercy, YES. All the YES. It’s those weird images that won’t fade, the tug inside that keeps telling you something either is or will lead to a key to the perceived but unknown. Thank you!