When people next to you begin to swipe left and right on bodies on their phones, the black glass like polished fulgurite, don’t feel like you have to feel left out just because you’re aro/ace. Join in their looking at the faces and chests, even if they have to tell you what makes someone attractive. The flesh is still beautiful. Beautiful because it is attached to real live people walking around in it all day, who wear it simply because it was given to them, this birthright, and you think that if there is something you love, it is this: what you share, this susceptibility to being punctured or pierced, to chronic illnesses like yours.

Too easy? Think of the ways you are loved, then, how you have been held by nights that asked nothing of you, stars and your breath beneath. Think of your mother, who has finally begun to stop responding you can still change your mind when you say you don’t want babies and now says maybe you’re right, and because you’ve been through so much pain already with your Crohn’s and I’ll admit I don’t want to see you have to go through any more, because this is an expression of love, and because I don’t want you to go through pain is near enough to you should want whatever you want. And your mother does love you, does want you to want what you want. She tells you your words are babies and when you wrap your arms around your mid-section, it is not a hand pressing out through you, it is something like a calcified prayer—that you want to be loved for more than womb and vagina and body, that you want to be held wholly by someone’s full attention without asking anything of you. Think of that red twisting umbilicus in you, your scarred and malfunctioning intestine, and remind yourself of how you are loved as this, swaying in the yellow light of a Colorado sun notching through the kitchen window. As someone who does not want to be cradled by a significant other when the gut pain is bad, though you feel like so many of the illness narratives you’ve seen include a steadfast partner. Who wants a cure for her disease but not her sexuality.

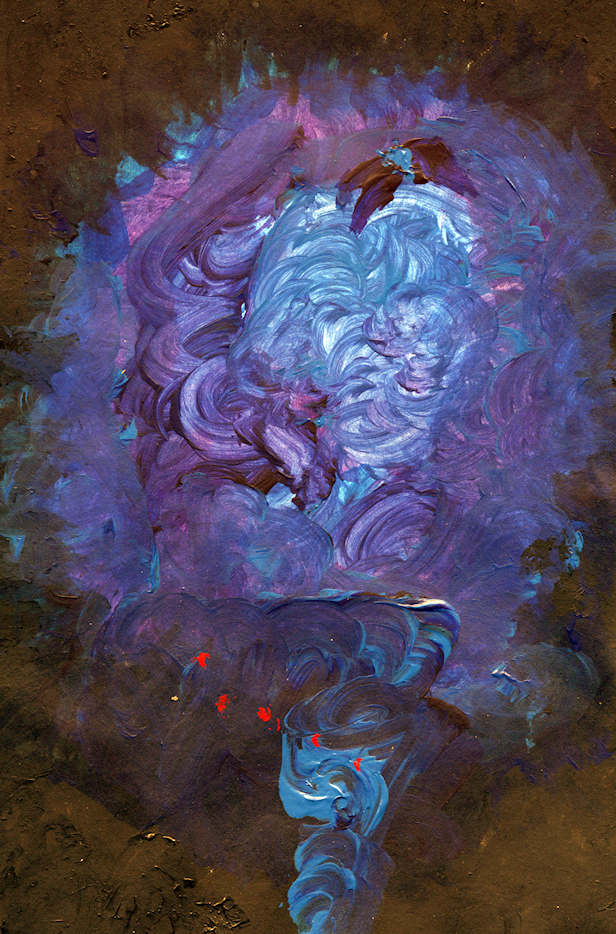

And when the screen makes you dizzy or your belly is tight, lock your eyes on the two cactus portraits in the living room. Drift, for a moment, through the frame of one and into the pink behind the green yucca, and imagine yourself by a silver river in high desert, wondering what you hold onto as other people discover love in such blue and scapular country at the doorstep of the Rockies. Imagine the prickly pear of the other painting, how you’ve seen clusters of succulent pads with spined areoles thirsting together in dry places, and you’ll have found your way precisely into the grief. Haven’t you imagined yourself so exposed this way, like those green bodies of the desert? Haven’t you imagined peeling back your clothing to reveal your breasts, matching the cacti nipples for needles, pulling away your breastbone’s skin and sternum to reveal the heart inside, something red and beating ringed with blue as you expose yourself entirely to suffering and grace?

This: acceptance.

This: home.

When illness is too much, when your gut burns, and you want to be held only in a platonic way, when you can’t find the corollary in your life to marriage and birth—what carves a sympathetic channel between these things—remind yourself of your mantra to friends lately: choose yourself. When it is not a choice at all, but who you are, choose yourself. Remind yourself that confiding how you spent two hours in the bathroom again to your roommate on the couch is still intimacy. That you have both told each other that if you were to shit your pants in public, you would trust her to help you clean up without shame. This, too, is love. And this, too, is love to not feel shame about your own body—or the absence of desire. Find what lives inside glass and flint and sunrise. Trade death for life and find the kindest part of yourself. Turn the words over and over again, you are enough, you are enough, you are enough; almost believe it. Hold onto what remains even when the flash of sight has disappeared: petrified lightning.

__

Kelly Weber is the author of the forthcoming chapbook The Dodo Heart Museum: A Fabulist Curiosity Cabinet (Dancing Girl Press, 2020), and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Missouri Review, Tupelo Quarterly, DIAGRAM, Cream City Review, Hobart, and elsewhere. She has been a finalist for the Frontier Chapbook Prize and Two Sylvias Chapbook Prize and has been longlisted for the [PANK] Nonfiction Book Contest, and her work has received nominations for the Pushcart Prize. She has served as an editorial assistant for Colorado Review. She holds an MFA from Colorado State University. More of her work can be found at kellymweber.com.