His shoulders hang low and his back is bowed. His body is forty pounds lighter than it was a few days ago, before the cancer surgery, before the blood loss that caused his mind to empty its memories. His is a body without strength, without vigor, without lust, without intention, without history. A body taken apart and reassembled, a body that has not settled into the space of gravity, a body that knows nothing about its own scars, crevices, grumbles.

His shoulders hang low and his back is bowed. His body is forty pounds lighter than it was a few days ago, before the cancer surgery, before the blood loss that caused his mind to empty its memories. His is a body without strength, without vigor, without lust, without intention, without history. A body taken apart and reassembled, a body that has not settled into the space of gravity, a body that knows nothing about its own scars, crevices, grumbles.

“Would you like to bathe your husband in private?” Nurse Jen asks, and I walk across hard linoleum, and I come to his side, and I say, “Yes.” She brings me a pink bowl filled with warm water where a bar of soap soaks. Nurse Jen lays out towels and a washcloth. She walks across the room and she pulls the curtain and she exits and the door closes fully behind her and the room is no longer open to the constant movement of others as it has been for the time we have been living in the cancer hospital.

My husband closes his eyes, and I take his hand in mine. The light of the new is in his thick fingers and large square hands. I squeeze the water from the cloth, rub across the soap, begin to make swirls in his palm, pressing into the flesh of the lifeline, stroking through each of the fingers. I lay the dry towel across his knees, and place his hand to rest there while I glide the cloth up his arm, softly caressing against the grain of his wispy black hair, smoothing over his wide shoulder. I lift his arm onto my shoulder and I rub under as the silky soap makes a trail into the pit, dark curls slick with lather. Once I could lick there, swirling his hair in my tongue, breathing in his scent as if to memorize the salty musk. Now there is no odor, except of chemotherapy, the smell of ice on steel. His skin holds the fragrance of his first cancer treatment: a scalding mitomycin liquid, isolated from Streptomyces lavendulae, a 104 degree tumor-killer which they’d poured inside him while his organs lay on the table near his open body. I imagine the medicine binding to his cells, the sick cells dying, the dead cells pouring out of him, onto my cloth. I imagine the movement restoring his mind, the mind we will not know for six months hence has been permanently altered by an anoxic insult, a brain injury, a memory-eater.

I soak the cloth in water again, and rinse him, warm droplets sliding down his forearms where I hope to wake something that wants to live, where I hope to rouse some fire under the pallor. I dry the length of his arm, almost as big as half of me, and so weak it flops to his side without support. I rub down his broad back, pat his left arm and hand, touch the skin tenderly, walking around the pole that holds his IV lines, avoiding the tape and tubes near his wrist. I wash the dried blood near his chest tubes, move the water away from the tape down his middle, a wide bandage over two feet long, where his skin is quietly re-stitching. He is without his umbilicus, the part that connected him to his mama, the center that made him man, the place where my fingers found him in the dark. My hand travels down to clean his penis, and I gently swab around the catheter, my hand finding his testicles, holding their weight in the way I would if I’d wanted to make love. I wipe him with sweet strokes. I look up to his face. He opens his eyes. Tender, surrendered eyes. Tears fall down my chin at the dignity in his submission.

I wrap him in his clean gown, and lean him back into a fresh pillow and strap on the leg bands that will pulse his blood through the day and night, making the sound of wind, a measured music in our unsteady life.

—

Sonya Lea writes for film, television and magazines, and has received screenwriting awards, including the Nicholl fellowship. Her book-length memoir, Wondering Who You Are, is about her husband’s cancer treatment, through which he lost the memory of their life. David Shields awarded her a Fish International Memoir prize for an excerpt from Wondering, which also won an Artist Trust Award in the U.S. Oprah Book Club author Bret Lott said of the work, “This story is strong and strange and haunting and moving all at once…[Sonya] has a voice and tone that are so truthful and authentic.” Sonya Lea has written for The Southern Review, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Tricycle, Cold Mountain Review, Side B, and for several anthologies. Originally from Kentucky, she lives in Seattle, Washington. You can find her at www.sonyalea.net and www.wonderingwhoyouare.tumblr.com.

—

Read Sonya Lea’s blog entry about this essay on the Brevity blog

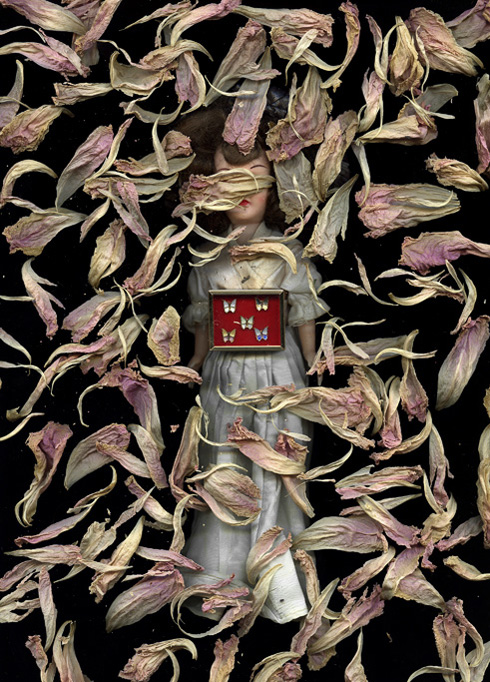

Artwork by Gabrielle Katina

23 comments

Lynn Phillips says:

Sep 18, 2012

beautifully written

Therese says:

Sep 18, 2012

Having been in the bathing situation after my husband had this same surgery, I feel every wipe of the cloth as if it were my own hand. What incredible writing, so full of passion and depth that it touches every core of my being.

Sonya Lea says:

Sep 18, 2012

Thank you, Therese. People who have been on both sides of this cancer surgery are so courageous to meet whatever comes. I appreciate you reading this work.

Lauren Gilkison says:

Feb 13, 2014

All your pieces are so beautiful,the love you share i can feel it as i read

marilyn krysl says:

Sep 18, 2012

This is prose, and as moving as Ingrid Wendt’s poem “BENEDICTION” about washing her mother’s body in her collection EVENSONG. Check it out…

Sonya Lea says:

Sep 18, 2012

I look forward to reading this poem. Thanks for suggesting it.

Marilyn says:

Sep 18, 2012

Takes me deep into the sensual memory of my bathing my sister in a white tub, stroking her lovingly with my hands, using a bar of oval pink soap that I still use now 2 years later. I too could feel every wipe as a deep communion in love. Thank you Sonya for your written prayers of the senses.

Sonya Lea says:

Sep 18, 2012

“written prayers of the senses” – I’ve never had my work known as this, and I will always treasure your words.

Carole Harmon says:

Sep 24, 2012

Those of us so fortunate to be led for awhile through the valley, the liminal time between life and death, know wonders and miracles as well as heartache and despair. “Written prayers of the senses’ seems such a perfect blessing for your writing Sonya. The gift you offer is this grounding of emotional and corporal experience in art.

Sonya Lea says:

Sep 25, 2012

Thanks Carole for your beauty. I also regard the liminal spaces as so fortunate to be invited into. Rumi said, “This being human is a guest house,” and I long to be cleaned out like old dust, in my writing and in my life.

Kathy Handley says:

Sep 30, 2012

I am deeply moved, and, if I were in your presence, Sonya, I would be speechless with the beauty of your words

Kathy Handley

Michael Frederick Geisser says:

Oct 2, 2012

Sonya, I am a writer who is still trying to find my voice. This story captured me like no other that I have read this year. Bravo! I notice how simple your sentences are, how you do not soar into flights of poetry, yet render a fully poetic work. I am jealous.

Debra S. Levy says:

Oct 6, 2012

Sonya, this is a beautiful, touching essay, to say the least. That last line — bravo.

Kay Wiermaa says:

Oct 30, 2012

This was so tender and beautiful…..my tears ran down as yours did in your story. Lovely.

Sonya Lea says:

Nov 6, 2012

Thank you for your moving comments. I’m editing the memoir now, and it’s good to know that some of the beauty of this time can reach others. Sometimes healing from such traumas can seem so internal.

Michael, I credit the ballast for my lyrical bent to my mentor, Priscilla Long. Pick up her fine work, “The Portable Mentor” and she will have you in your authentic voice through something quite counterintuitive — copying the master’s strategies.

Jon Zech says:

Nov 19, 2012

I’ve been on both sides of cancer, been the bathed and the bather. It was never beautiful until now.

Rajesh Kumar Sharma says:

Dec 14, 2012

So the Stoics do live among us too! The courage, the frugality of emotion, the splendour, the taste of mortal joys…. Thanks. I returned to reading Brevity after a long,long time. (Once published a piece on this beautiful site.) I return immensely rewarded. Thank you.

Sonya Lea says:

Mar 12, 2013

Jon Zech, what sweet to experience both sides. Thank you for your connection here. Rajesh Kumar Sharma, I’m so pleased you are back to this amazing publication. Dinty Moore is teaching me a great deal here. With gratitude for your kindness, Sonya.

Sonya Lea | B O D Y says:

Apr 1, 2014

[…] Memoir excerpt in Salon Non-fiction in […]

Kassandra miranda says:

Aug 26, 2014

This just really brought to mind what my mother, aunt, and grandmother went through as my grandfather faught cancer. It also made me think of what he may have felt being in that position.

John says:

Jan 12, 2015

I am a young man, and I’ve never had a loved one fight cancer. With this in mind, I’ve only been moved this deeply by someones literature a few times in my life. Truly beautiful.

Sonya says:

Jul 5, 2018

John, Sorry it took me so long to say thank you. I didn’t know your comment was here, and it came at a time I really needed to hear this kindness.

Kathy Buckert says:

Mar 15, 2015

This piece reminded me of my husband lovingly washing my hair after my cancer surgery. Eventually he shaved my head, the hair that attracted him to me was no longer fell to the floor of our tiny pink bathroom. Thank you for sharing such a personal and beautifully written essay. There was so much devotion in each movement, each word, each gesture of kindness.