One morning I watched—through our ground-level bedroom window—the steps of his work boots, back not thirty minutes after he had left for a new job in town.

One morning I watched—through our ground-level bedroom window—the steps of his work boots, back not thirty minutes after he had left for a new job in town.

Fired.

I never knew why, and he claimed not to know.

He lumbered around unsettled, rewiring our bedroom or checking mystery switches, wrapped in his tool belt, eyebrows fixed in distraction. He grumbled about the mess of cords beneath my desk, the danger of knots, the snarl of sure fire. He straightened the cords, wound them into a tight circle, then secured it with a black twist tie.

We lived underground, a small living room with a bookcase in one corner, a desk in the other. Most of the time, he was gone, working in refineries across the country, fitting pipe. Four weeks in Nebraska, two months in Texas, a short stint in Louisiana. I can still feel him coming home, heavy boots on the stairs, large shoulders ducking under the frame, the way he’d lean down and pick me up, his whispers fast rapids over rocks. He was a blend of beard, flannel, and long roads I still carry—like a receipt for a book tucked into its pages.

I remember the way snow suffocated the windows and barricaded our only door. Alone for long stretches, I’d write words, save them to read aloud when he could listen. It was like sitting inside the missing.

Every now and again, I’d get up and walk into the kitchen, stare at the list on the refrigerator. I had been circling words in books I didn’t know. Looking up definitions. Writing them down.

sclerotic—rigid and unresponsive, unwilling or unable to adapt

aporia —a simulated or real doubt

incondite—ill-constructed, unpolished or rough, crude

delphic—obscure, ambiguous

farrago—a confused mixture, a medley

chthonian—of or relating to the deities, spirits, and other beings dwelling under the earth

The days wore on, only simple words between us.

One afternoon, he came into the kitchen to find me staring at the refrigerator mumbling, working to unknot the definitions.

He told me how he spent a lot of time in junior high at the house of his neighbor, Kevin, and Kevin’s mother was an English teacher, and Kevin’s mother kept a list of weekly spelling words on the refrigerator, and Kevin’s mother would ask him, every time he came over, to spell one of the words, and Kevin’s mother didn’t understand why he stopped coming over. Take down the list. Please.

A few days ago I told a friend about that moment, and he suggested I write a story about me taking down the list and leaving with it.

*

I still twist ties around cords, each turn an electric memory—his calloused hands moving over my body, our smoldering distance, the rush of snow against small windows.

__

Jill Talbot is the author of The Way We Weren’t and Loaded: Women and Addiction, the co-editor of The Art of Friction: Where (Non)Fictions Come Together, and the editor of Metawritings: Toward a Theory of Nonfiction. Her essays have appeared in or are forthcoming from AGNI, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, The Normal School, Passages North, The Paris Review Daily, The Pinch, The Rumpus, Slice Magazine, Sweet, and more.

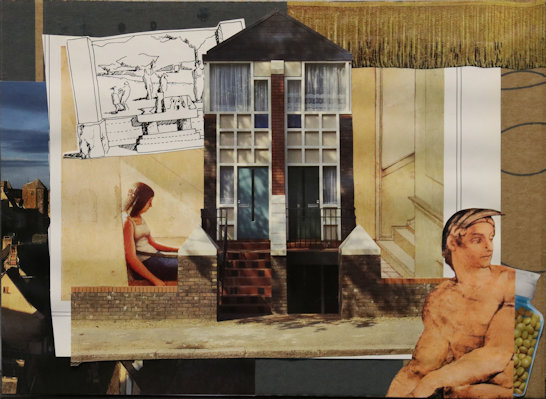

Artwork by John Gallaher

13 comments

Judith Gelt says:

May 17, 2018

I love how the concrete details paint this powerful emotional picture. Your work is inspiring, jill!

Ryder Ziebarth says:

May 17, 2018

“It was like sitting inside the missing.” So many beautiful sentences, Jill, but this one. This one.

Amy Wright says:

May 17, 2018

What pleasure coming to those windows, Jill–like rounding the bend of a river and meeting those “fast rapids over rocks.” Your words and descriptions here are so sensual and richly complex–with the cords and chords of a polished melody. I’ll be sure to share it with my students.

Ceci says:

May 21, 2018

Beautiful. I feel it right to the bone. I agree with Ryder about “sitting inside the missing.”

daisy hernandez says:

May 30, 2018

Gorgeous.

Alicia says:

Jul 2, 2018

“I still twist ties around cords,” too.

Steve Harvey says:

Jul 4, 2018

“…sitting inside the missing”–haunting.

Sejal A. Shah says:

Jul 22, 2018

Such tension and beauty!

Jenn says:

Aug 8, 2018

Wow. Powerful. The claustrophobic feel you’ve achieved is so strong and fitting. The push pull of your conflicted feelings—I end up feeling for both of you.

Rick says:

Aug 17, 2018

Love the closure…”the rush of snow against small windows” the inevitability of it all. Beautiful work.

APRIL K PFROGNER says:

Aug 31, 2018

i love this!!

bev says:

Sep 17, 2018

There is so much subtle tension in this piece of writing. I especially love the small parts of it that make the narrative so meaningful: the title, the unresolved longing at the end. You simplify the complexity of love and offer a look into such an intimate relationship. Thank you for a beautiful and truthful story!

Katrina Samonte says:

Sep 19, 2018

I love how the title means fear of words, while the words of your piece are so detailed and beautiful. I can fully imagine everything in my head while reading this piece. I loved the line “I still twist ties around cords, each turn an electric memory.”