I snuck into my teacher’s house with L.—she’d never been inside. I lived in the apartment out back, up three flights of rickety stairs. For hours every day, the dalmation, Pal, clanged her chain up and down my stairs, like Igor, some damned thing. At the landing, she’d peer into my window screen, a shadow dog, clank back down. My teacher/landlord was away for a couple days. The house a hundred-year-old mansion he’d bought with his book money. On Lake Charm. I like old houses, but his spooked me—like being inside a game of Clue, the rooms always unfamiliar, angular, humid, the house too large to air-condition. He’d loaned me a copy of Breakfast at Tiffany’s with black mold on the pages.

I was not allowed in the house while he was gone. But a door from my apartment led to a stairwell and the kitchen below. He liked to keep it unlocked he said, in case of fire. He was long divorced from a tiny, blond ballerina and was having a secret affair with a student in my class, another tiny, blond ballerina.

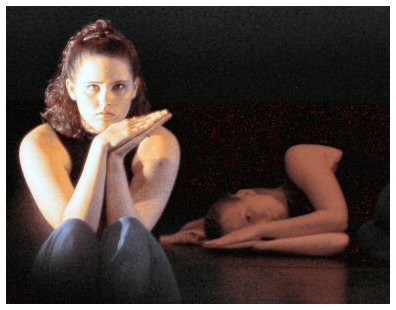

So. L. came over, brought her camera. In one photo, I wore an antique-y sleeveless dress and bone fishnets, posed shoeless on the porch hammock — one foot in the air. For another shot, I leaned over the widow’s walk to wave at L. on the front lawn. Far inside the house, we found a tiny room off the kitchen, a stuck doorknob, so I’d leaned into it. When the door opened, something crystal or glass crashed to the floor. It was odd, as if it had been placed to fall if the door was opened. There may have been a key in the door. Shutting it, I saw a murky window that looked out onto the yard.

There had been other student affairs by then, another blond undergrad who interviewed him for the paper, saying she wanted to capture his flavor. He took her to a dark country bar on highway 50. A black-haired young woman who looked like a twelve-year old boy. After my teacher returned, he stood in the yard, holding an opened package. I came downstairs, hoping to get into my car, but he called me over. He said there was a little room off the kitchen, a room where he did some writing — he kept an old typewriter in there — and some object in the room was now broken. I smiled patiently, too nervous to hear exactly what I’d broken. He spoke very, very slowly. A game to make me confess, and the game made me angry.

He stared at me silently, pausing several times to do this. Then he took a book out of the package in his hand, saying it had arrived with no return address. It was Ann Bernay’s Professor Romeo. He asked, Why would someone send this? Did I have any idea? I thought the book was brilliant, necessary. His perplexed face—how could he be surprised? It reminded me of my own pretending.

But when I’d been twenty and drinking every day, late for classes, absent for weeks, he had been my only friend at school. I’d sit on the couch in his office with the naked female mannequin and wall-sized collage of models from magazines, and be calmed. He was fond of me like a troubled character in a novel, pulling for me, But I’d dropped out, gone to work at a health food store, where the owner would say, You may be book smart, but you sure are stupid, and for years my teacher would come in, buy vitamins, say, Come back to school. So, I did. He’d rented me the apartment.

By the time I finished grad school, I’d moved away from Lake Charm, and he had brain cancer, seizures, trouble teaching. A red-haired girl loved him. The Department Chair asked if I would take over his classes for the semester, if necessary. I said, Yes. A guilt close to my guilt over the dalmation.

I’d seen another dog with Pal in the yard. She’d been old then, elderly even—I should have chased off the male dog but was unsure what to do, how to interrupt behind glass. Pal had puppies in the garage, and that year she died. When the puppies were just born, suckling, exhausting her, hills of vanilla-colored blankets surrounding them, my teacher had asked over and over, How could this happen? His questions always soft, as if he were only talking to himself, overheard.

Kelle Groom has published fiction in The Southeast Review and poetry in Agni, Doubletake/Points of Entry, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, Poetry, The Texas Observer, Witness, and other magazines. Her poetry collections are Underwater City (University Press of Florida, 2004) and Luckily, the 2006 Florida Poetry Series selection (Anhinga Press). Her awards include the Norma Millay Ellis Fellowship from the Millay Colony and a Tennessee Williams Scholarship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She works for the Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach, Florida.

photo by Dinty W. Moore