This morning while I was running, shoes smacking the pavement, Venus bright above the spine of the Bear Mountains, and my thoughts pinned to the day ahead, the meetings, the deadlines, the writing I would not do, a deer was hit by a car. It flew in front of me, disrupting the morning stillness, veered close to my chest, and then into the oncoming lane; for a moment, its legs silhouetted against the headlights of the SUV like a shadow puppet. Perhaps a mother scurrying after her baby who had already crossed the street. Perhaps the baby chasing its mother’s tail, too young to know of cars or roads or the way high beams devour your ability to see in shadow.

Is the deer okay? the woman asks, stepping from her car, the interior lit by the opening of her door, bright and warm in shades of beige, the silver glint of a coffee mug like a lantern on the dash.

I don’t know, I respond, my mittens still over my mouth. And I move from worrying about the deer to worrying about this stranger in the dark, bundled in a red jacket that she zips securely under her chin. You barely hit his legs, I say, consciously choosing the gender, thinking the loss of him is somehow less than the loss of her on this still-dark morning.

Are you okay?

Yes, she says. I’m sorry.

It’s okay, I reassure her, they always run across the road.

And I turn from the brush on the side of the road to resume my run.

A crack, I think, as I move down the hill, the sound of bone breaking, delicate but decided. She is not okay. Fled to the brush but not to safety. She will die, maybe not today but within weeks, unable to graze the valley floor or shot by a hunter during the season that opens in a week. A crack is what I remember now more than the legs held in amber. The pounding of my feet, always a flat runner, never with the kick of a marathoner, never light and nimble, suggests with every stride that I caused the deer to scurry from the brush and into the road.

I’m sorry, she says to me, the only witness in the dark, and I forgive her because that is what you do. They always run across the road.

She doesn’t know I am to blame.

This morning I hit a deer while running. Most likely she is dead. By the bottom of the hill, I have opened Toni Morrison’s “menu of regret.” My failures spill freely onto the pavement, the accident having driven a wedge into the room of my heart that I try to keep locked. People don’t like mean boys, I say to Aidan, No one will play with you. And when Kellen butts his toddler head into mine because he wants another story, instead of opening Goodnight Moon again, I dump him roughly into his crib. My friend has no children, has no job, writes all day in her windowed house high in the mountains, while I steal two hours at a noisy bookstore before I head to campus and cut corners on my teaching, send apologies over email like Valentines. When I was seven I hurt my father. At thirty-seven I did the same. I steep anger into my husband’s morning tea.

Orion fades above me in the bowl of sky, while dawn simmers at the ridgeline, black to blue, providing only enough light to reveal the school children huddled together for the bus. Where is the deer now? Lying down beneath the stars, licking a wound that she cannot heal? How will I protect my sons from this world, from the way it breaks you open, from a mother who used to do everything well and now limps through the day?

Jennifer Sinor is the author of The Extraordinary Work of Ordinary Writing. Her essays have appeared in The American Scholar, Fourth Genre, Bellingham Review, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing at Utah State University where she is an associate professor of English..

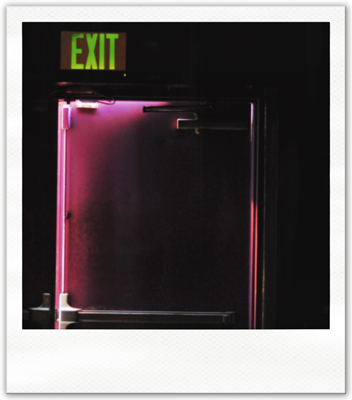

photo by Leslie Miller