A baby hand, grubby and dusty, popped from the left the moment I opened the lunch box.

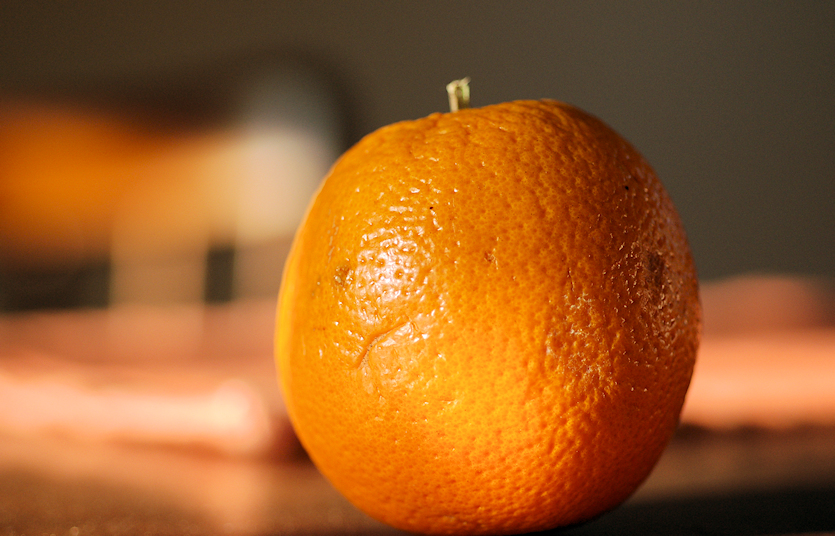

The train was pulling out of the Ludhiana railway station after a five-minute halt. The sun, a mildewed orange peel, was going down behind the dust and smoke of the industrial city. The train had been late, and I had not eaten anything since breakfast. All around me people were eating, and their sight had quietly disturbed my hunger.

Without turning my head, I rolled my eyes to the left. The little boy took two steps and stood before me. He was four or five years old, and was wearing the oversized rags of charity, the pants held up with a cord. His palm was stretched for begging in an easy, accustomed gesture. Red and green streaks ran across the grimy face: someone had obviously tried to paint colorful mustache and whiskers to make that face fascinating and, perhaps, adult. But the colors had got overwritten and almost lost under the grime.

He wants a portion of my meal, I thought, for in his other hand he was already holding a chapati.

I find it very uncomfortable having to eat my meals in a train. The dirty little child, with his dirty little hands begging for food, the sight froze me with a vague embarrassment and indecision. Before I could react to his sudden appearance, he had vanished into the crowd, perhaps drawn by better hope.

Half an hour later, he reappeared. This time he carried a small ring, made of hard steel wire, and was accompanied by a girl, about ten years of age, who had very short hair and carried, under the right arm, a small drum.

She settled down on the floor of the passage and began to beat the drum. The little boy struck a few poses and then broke into a dance. He danced in rhythm but not to the beat of the drum. An entirely subjective rhythm, sealed, and inaccessible to spectators.

The passengers in the train were an assorted lot. A young man promptly established a cordial eye contact with me and smiled, as if to express his appreciation of the absurdity of the children’s theatre. The Indian classical dances are all rooted in drama, in acting, abhinaya – as it is termed in Sanskrit. In Kathakali, the famous dance of Kerala, the dancers paint their faces in symbolic colors to enact characters from the epics. Red and green are among the colors they put on faces.

But the dance was a mere prelude. The little boy soon began the acrobatics, twisting his tender body into knots and passing, in different styles, through the steel ring. The girl, meanwhile, continued to beat the drum, with no change in rhythm, no break, uniformly, mechanically, without a speck of interest. Her eyes were looking at nothing, not even at her artiste companion, who was probably her brother. The boy too, I noticed now, was not looking at anybody. One couldn’t tell what their eyes were seeing, because they seemed to be looking at nothing.

When the performance ended, the girl stood up and leaned against a seat back, and continued her objectless gazing. Perhaps she was gazing beyond space into pure time, an act impossible for me to comprehend and mimic because I have a location, a station, whereas she lived between the stations, going from nowhere, to nowhere, lived only in time, without space, and survived only on time.

The baby-hand boy held out his half-open palm again, clutching a few coins with three fingers in an attempt to persuade the spectators of his performance to pay for his art and labor. He presently received two coins.

Then he went and stood before the young man who had smiled to me. He and his friends began to laugh to see the little boy spreading his hand before them. They told him to go away. But he stood there, mute, and immobile. They kept laughing, and he waiting, until sleep overpowered him and closed his dirty little eyes. And then he swayed in sleep, like a ship tossing, and that really disturbed the young men who didn’t want any contact with dirt. They shouted, angrily and loud.

But even that didn’t break the tired artiste’s sleep. He didn’t move a step.

Until his sister dragged him away, for another show.

Rajesh Sharma‘s work has appeared in spark-online and the Chandigarh Tribune. He teaches English to college students in a semi-urban college in the city of Hoshiarpur in Punjab, India.