The brief and interminable year that I was involved with the Northwestern Bell repair tech with the clubbed thumbs seemed to include three or more New Year’s Eve parties. Were there three parties on the same night? Were there three December 31s in the same year? I don’t remember. Perhaps it was just that our doomed-from-the-beginning relationship was always on a sparkle ball countdown to the inevitable end: Three, two, one. Done. At every New Year’s party that I attended with my inevitable ex, CJ Wright wore a pink tuxedo shirt with pleated front, banded collar, and linked cuffs. She drank Dewar’s neat and combed a side part into her hair. She helped herself to little tastes off peoples’ plates and complained about the music in a fake British accent. I remember her with a different date at each party who all shared the same embarrassed look when CJ started hip thrusting on the dance floor to She’s a brick house. CJ was so queer she made the rest of us avert our eyes and duck our heads, like when you’re watching a contestant on a game show who just doesn’t have a clue and everybody else gets it before they do and then slowly they start waking up to the fact that they are too stupid to live and you can see it happening right before your eyes on national television, right in your own living room, ain’t holding nothing back. This was when the downtown queers were pale skinny girls and uniformly tan ex-cheerleaders. There was queer and there were the queer queers like CJ, a boyish girl with too-big hips that pooched out the pockets of her creased chinos. CJ thought her life would be redeemed by true love, a lap dance from Princess Diana, custom-tailored Oxford shirts.

The brief and interminable year that I was involved with the Northwestern Bell repair tech with the clubbed thumbs seemed to include three or more New Year’s Eve parties. Were there three parties on the same night? Were there three December 31s in the same year? I don’t remember. Perhaps it was just that our doomed-from-the-beginning relationship was always on a sparkle ball countdown to the inevitable end: Three, two, one. Done. At every New Year’s party that I attended with my inevitable ex, CJ Wright wore a pink tuxedo shirt with pleated front, banded collar, and linked cuffs. She drank Dewar’s neat and combed a side part into her hair. She helped herself to little tastes off peoples’ plates and complained about the music in a fake British accent. I remember her with a different date at each party who all shared the same embarrassed look when CJ started hip thrusting on the dance floor to She’s a brick house. CJ was so queer she made the rest of us avert our eyes and duck our heads, like when you’re watching a contestant on a game show who just doesn’t have a clue and everybody else gets it before they do and then slowly they start waking up to the fact that they are too stupid to live and you can see it happening right before your eyes on national television, right in your own living room, ain’t holding nothing back. This was when the downtown queers were pale skinny girls and uniformly tan ex-cheerleaders. There was queer and there were the queer queers like CJ, a boyish girl with too-big hips that pooched out the pockets of her creased chinos. CJ thought her life would be redeemed by true love, a lap dance from Princess Diana, custom-tailored Oxford shirts.

Auld lang syne

In the new year the repair tech and I broke up. I grieved a future of inconveniently placed phone jacks and wrong numbers. This was a time, however briefly, when I lamented the waste of tenderness in the world: those dear thumb stubs, the rotting bouquets piled outside Kensington Palace. CJ gave up tuxedo shirts and everything that wearing a tuxedo shirt implied. She grew her hair out, renounced the devil, and married a deacon at a big box church. Her husband wore Sansabelt slacks. How is that possible? None of us were invited to the wedding. None of us knew what CJ stood for—Carol Jean? Claudia Jo? Cracker Jack? If it was possible for CJ to become unqueered and become a plain-faced Wisconsin farm wife, to leave us behind like a fever dream—could we too become something different, learn to strip our own wires, make new connections, sweat out the same sex sickness? What was possible for any of us?

She’s the one, the only one

That year we all wore pink tuxedo shirts at the New Year’s Eve party in CJ’s honor, like a team uniform, to honor choices lived and left behind.

Wait, I’m sorry. That last part isn’t true. The part about the New Year’s Eve party is true, but nobody wore a pink tuxedo shirt. It was a new year, and whether CJ was doing shots and licking salt from a woman’s naked breasts or sipping iced tea with the Christians in a church basement has nothing to do with redemption—hers or ours.

—

Lynette D’Amico is an MFA candidate in fiction at Warren Wilson College. Her novella, Road Trip, was short-listed for the Paris Literary Prize and she has a story forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review. Most recently, she lives in Boston, which is still news to her.

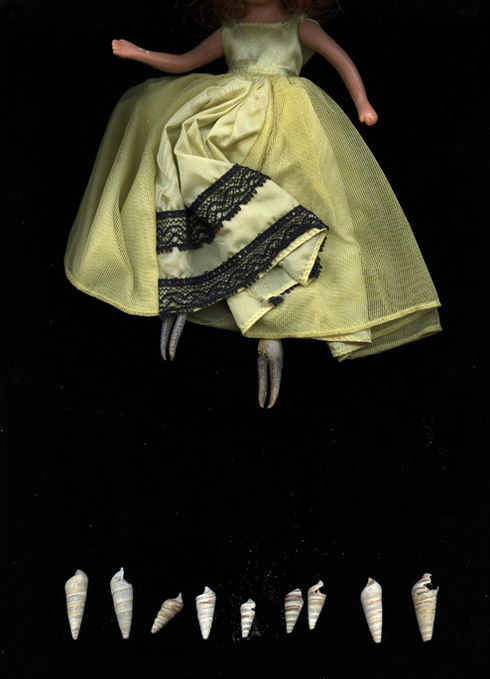

Artwork by Gabrielle Katina

3 comments

Dan Miller says:

Sep 18, 2012

What a beautifully evocative memoir. And very witty, too:

>>> I grieved a future of inconveniently placed phone jacks and wrong numbers. <<<

Eagerly looking forward to Gettysburg.

Debra S. Levy says:

Oct 7, 2012

Lynette, a wonderful essay — the way memory is presented here is powerful. Looking forward to reading your piece in The Gettysburg Review.

Kelly Stecher says:

Oct 8, 2012

I had a lot of fun reading this, was disappointed to see it end! The story, I mean, not the relationship!