At 19, I moved to Las Vegas with my boyfriend Scott. Things were fine before the move, but after arriving in Nevada—1,300 miles from home—something seemed off. While Scott and I waited for a cab, other men glanced at me, and Scott locked his eyes on my body to signal ownership. He didn’t like my clothes and insisted I buy a new wardrobe. It was not the romance I’d imagined, but I thought it could become that. So I stayed.

I stayed long enough for him to spit in my face, call me a cunt, punch me in the back of the head so hard it swelled. I stayed long enough for him to wrap his dense hands around my neck and threaten to not let go. These incidents didn’t happen at once and were sprinkled in between soft kisses and long talks, shared bowls of Thai noodles and late-night tickle fights. It was textbook: when Scott lapsed into violence, he begged for forgiveness.

How hard it is to know for certain something is irrevocably wrong; how hard a young heart yearns to trust even those it knows it should not.

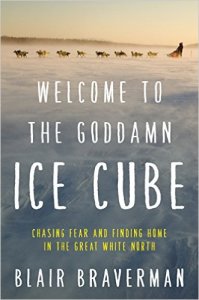

These were the things on my mind when reading Blair Braverman’s debut book Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube, a memoir about a young woman’s attempt to answer “private questions about belonging and violence and cold” by going North. As a young girl from California, Braverman was romanced by the North, and she immediately embeds us in Norway on what is her seventh trip there. We learn Braverman wants something from this rural isolating land: for it to make her whole again. But we only learn the origin of her brokenness in batches.

Ice Cube is divided into two timelines, the present and the past. The present narrative focuses on Braverman’s relationship with a shopkeeper named Arild, who gives her room and board and asks her to curate a small museum. The second thread reveals why Braverman is occupied with questions of violence. At age sixteen, Braverman lived as a foreign exchange student with a family possessing its own brand of dark secrets. A brochure instructs her to call her foreign-exchange parents Mor and Far—mother and father in Norwegian—but when Braverman greets them this way, they respond with uneasy silence: “I realized almost immediately… that to use such intimate language was a mistake.” But Braverman continues the false intimacy, which becomes disturbing as we learn there is something creepily off about Far: “I felt it a thousand times at a thousand moments—from a glance, an expression, a lift of his chin. …Something felt wrong again and again, and yet I could never say for sure, even to myself, what it was. I was never even confident it existed.”

As the story with Far unfolds, the reader is made complicit: the safety of our narrator is at stake, yet we yearn to know just how far Far will go. The tension is palpable, and I wondered if Bravermen would successfully supply a satisfying denouement. She does so swimmingly. When the year is up, Braverman returns to the States, but changed, darker. Feeling cheated, she returns to Norway to re-appropriate her experience. This time she attends a folk school to learn to drive sled dogs. It’s here we meet Arild, who serves as Far’s foil and provides an anchor for the book. Arild is a man full of eccentricity and charm: he calls his oldest customers “young man” and children “geezers.” But Braverman avoids sentimentality by rendering Arild with complexity: the same man who gives her wool sweaters makes a tasteless rape joke at her expense. Arild seems to be a good man, but he is still a man, and in the climate that is Braverman’s book, he is not wholly innocent of the sort of violence Braverman is trying to transcend.

There are moments where Braverman falsely inflates narrative stakes, moments that do not in fact yield anything. But these moments of suggested drama are rare, and Braverman is such a skilled storyteller, when one tension dissolves, she supplants it with a livelier one. This book could be described in a dozen different ways— hero’s journey, coming of age tale, travelogue, character portrait, elegy of place—but no description would get at root of this book, which is about gender and violence and belonging, but most of all about being human and learning to live—and trust oneself—in world where things aren’t always safe.

__

Chansi Long is a graduate from the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa. She’s been published in the Washington Post, the Essay Daily, and the Iowa Daily Palette, among others.

1 comment

Elizabeth Osta says:

Jul 9, 2016

Enjoyed this review from the very beginning. Belonging needs to be safe and when it isn’t we need to know where to go. Ms Braverman offers a place and Ms Long points us there with sharp accuracy.