Mother is gone. One day I’ll pick up the phone and hear one of my sisters saying these words. Mom’s eighty-one now, and though she’s in relatively good health—survived two bouts of cancer—I know her life can’t go on forever. Mother tries to prepare me. She discusses her bank accounts, goes through her list of keepsakes, and asks me to help her order a tombstone.

Mother is gone. One day I’ll pick up the phone and hear one of my sisters saying these words. Mom’s eighty-one now, and though she’s in relatively good health—survived two bouts of cancer—I know her life can’t go on forever. Mother tries to prepare me. She discusses her bank accounts, goes through her list of keepsakes, and asks me to help her order a tombstone.

I’m stoic. Every time I lift this veil, gaze at what life will be like after Mother, I see darkness.

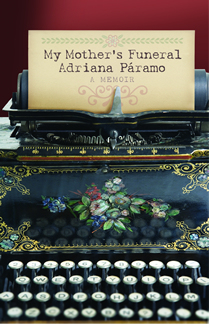

So Adriana Páramo’s memoir, My Mother’s Funeral. not only goes to a place I’m reluctant to go, but opens with the dreaded call. “I collapsed in slow motion,” she writes about hearing the news. “My body trickled down a wall until my chin touched my knees. I thought about Mom’s face, but couldn’t see it. I could see her eyes but not her nose, her lips but not her neck. The rest of her was in bits and pieces. Her winter hands, her velvety ears, her porcelain left knee, her night hair. Mom was fragmented now. She used to be whole.”

Páramo shares her shock and grief with such honesty and originality that one can’t help but read on. These elegant, interwoven essays crisscross over time—showing her mother’s innocence and desperation, eloping with a man who’d only bring her disappointment, going forward to Páramo’s childhood and rebelliousness.

Carmen, Páramo’s mother, suspects on her wedding night she has made a dreadful mistake. Her husband leads her to a shabby brothel with stained sheets where he takes her virginity. Carmen’s dreams end as she discovers the man she loves is not as attractive as she thought, in addition to being alcoholic, crude, and unfaithful. After the birth of their sixth child, her husband takes off without a word for twenty years, leaving the family penniless. Carmen copes making soup out of bones, guiding her children so they grow with love, self-respect and independence.

She strives most to protect her daughters from mistakes she made—knowing that men and sex can result in dead-end traps. Thus, Carmen obsesses about her girls’ virginity. However, Páramo is as high-spirited and independent as her mother. One night, when she’s just thirteen, she goes on a bike ride with a boy from school. They kiss, but that’s all. He smokes marijuana, and they both end up high and asleep. Páramo wakes up to realize she’s missed her curfew. To avoid her mother’s scorn, she steps in front of a motor scooter, hoping to land in the hospital. At least she’d have an excuse for being so late. There’s a collision, but no injuries. She makes up a story about being kidnapped. Horrified, Carmen takes the girl, the next morning, for a pelvic exam, which proves she’s still “in tact.” Carmen rewards the girl with the “pixie cut” she has long wanted.

That night, Páramo looks hard at her mother. “Late forties, dark half-moons under her sad eyes, short gray hair, a permanent frown, dark unsmiling lips—a haggard woman with nothing to show for a lifetime of diapers, late-night colics, schools, unpaid bills, hunger, lies, loneliness,” she writes. “I walk to the couch and sit beside her. She puts her arm around me. For a while I sit rigidly, but then I feel like crying for her.”

When her mother asks her why, she replies, “I’m crying for you, Mamá.”

“That’s silly,” she says.

When Carmen dies, Páramo is living in Florida—a hemisphere away. Even so, she pictures her mother’s last night in Columbia—death as a vacuum that “sucked upward with a violent jerk as if an invisible parachute had opened above [Carmen’s] head.”

It takes her to “the place she loved most in the world, Mariquita…that smelled of avocado and earth after the rain.” Páramo tells her goodbye, believing her mother has returned to being Carmen—just Carmen—the girl with big dreams, love, and hope.

__

Debbie Hagan is editor-in-chief of Art New England and book reviews editor for Brevity. Her essays have appeared in Brain, Child, Flash, Don’t Take Pictures, and elsewhere.

2 comments

Fran Folsom says:

Jul 27, 2014

Excellent review. This book sounds so interesting I can’t wait to read it.

Fort says:

Sep 3, 2014

You say it well . It is a wonderful history . I would liked to read the book .