When the package containing David Quammen’s Spillover arrived on my doorstep one morning, I cracked the book from its cardboard shell and set it on my bed for evening reading. But I returned later to a crime scene: the book splayed on the floor, its hard cover dismembered, and the first chapter merely shreds hanging from a naked spine. It looked like the work of Tiger, my omnivorous husky-terrier mix. I resurrected what I could, but I had to order a copy from the library.

When the package containing David Quammen’s Spillover arrived on my doorstep one morning, I cracked the book from its cardboard shell and set it on my bed for evening reading. But I returned later to a crime scene: the book splayed on the floor, its hard cover dismembered, and the first chapter merely shreds hanging from a naked spine. It looked like the work of Tiger, my omnivorous husky-terrier mix. I resurrected what I could, but I had to order a copy from the library.

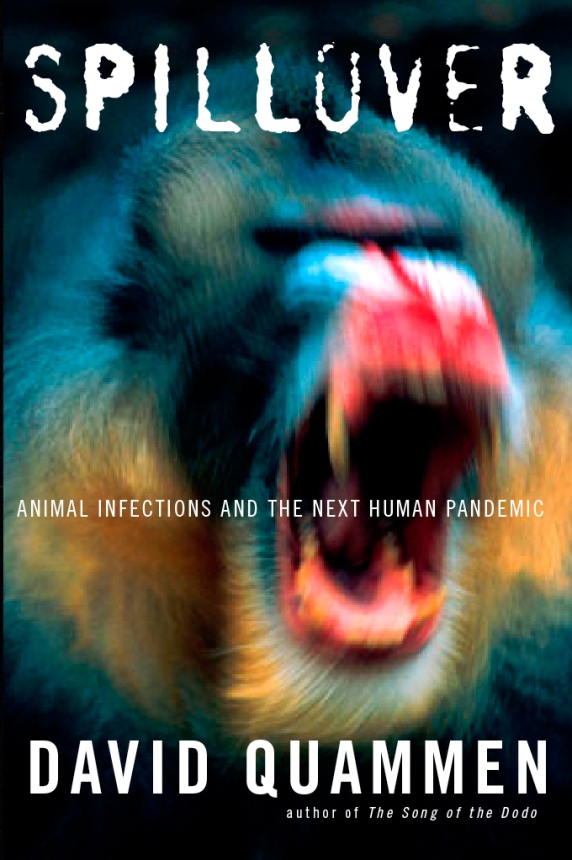

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic (W. W. Norton & Company, 2012) tracks the intrusion of zoonotic viruses into human populations. People like me sometimes need our books ravaged by dogs (that most invasive of species) in order to puncture our notion of nature as something “out there,” beyond our insulated windows and caulked doors. Quammen’s premise is precisely the opposite: we are nature, situated (obliviously) within complex, finely tuned ecosystems, which we all too blithely disrupt. As such, we are highly vulnerable to microbes that “spill over” into new host populations—wild geese, macaques, gorillas, and bats, as well as domesticated livestock and pets.

Soon after I finished the first chapter, on the Hendra virus, the library recalled this much sought-after new book, so I read the rest from my frayed copy, whose first thirty-three pages fanned out like feathers—an irresistible dog toy—when I tried to hold the book upright.

Quammen, a science writer well known for his books and National Geographic articles, elucidates difficult concepts from specialized fields (microbiology, virology, and epidemiology) using creative nonfiction techniques. There are vivid first-person scenes and engaging, sometimes quirky characters. There is intrigue. There’s direct address. There’s fresh and surprising language (a virion “may be festooned with a large number of spiky molecular protuberances, like the detonator stubs on an old-fashioned naval mine”).

Above all, there’s narrative. Each chapter follows Quammen’s geographical and conceptual journeys to understand a specific virus (Hendra, Ebola, the malaria virus, SARS, Lyme disease virus, Herpes B, Nipah, HIV). These narratives interweave with other journeys, both literal and metaphorical. We follow Quammen as he tracks virology developing as a field and viruses journeying from species to species, ending in human mouths or lungs or blood. These interwoven narratives culminate in Quammen’s tour-de-force imagining of the journey of HIV, around 1908, from a small village in southeastern Cameroon, down the Sangha and then Congo rivers, to Brazzaville and Léopoldville, and beyond. By this point, it would be hard for a reader to deny Quammen’s central thesis, so viscerally shown as well as told throughout the book:

…zoonotic diseases…remind us, as St. Francis did, that we humans are inseparable from the natural world. In fact, there is no “natural world,” it’s a bad and artificial phrase. There is only the world. Humankind is part of that world, as are the Ebola viruses, as are the influenzas and the HIVs, as are Nipah and Hendra and SARS, as are chimpanzees and bats and palm civets and bar-headed geese, as is the next murderous virus—the one we haven’t yet detected.

A book with such a theme might sound scary and depressing. But the writing is so alive and fecund, I kept the book on my nightstand and looked forward to reading it.

Each night the book got a little smaller. One night I woke to the sounds of tearing and masticating. Tiger was systematically exfoliating the pages strip by strip. To appease my anger, he slathered my mouth and nose with his saliva, hosting who knows what pathogens. Another night, as I read, a comma began crawling across the page, transforming into the dreaded, dog-borne flea, so heavy with blood it was easy to squash. It could easily have been carrying the DNA of the next pandemic.

—

Deborah Thompson is an associate professor of English at Colorado State University, where she helped develop the new master’s degree in creative nonfiction. She has published numerous essays in literary criticism and nonfiction.