If you’re lucky, you’ve had someone to talk with about things—someone to answer, “That’s right, that’s right,” to what you’re trying to get at.

If you’re lucky, you’ve had someone to talk with about things—someone to answer, “That’s right, that’s right,” to what you’re trying to get at.

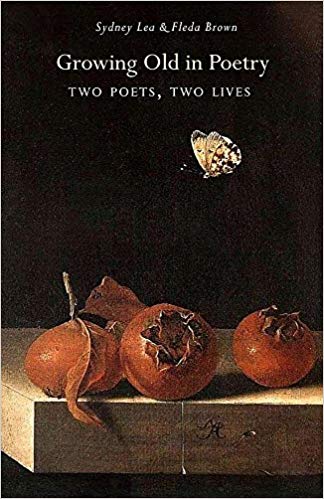

The pleasure of reading these letters/essays between Sydney Lea and Fleda Brown is being able to answer, “That’s right,” as we follow their takes on books, food, music, sex, politics, and writing and teaching poetry. Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives is, first of all, an exchange of essays on the writing life. It is also, as they tell us, a “record of an important friendship.” In this, Lea and Brown, past poets laureate of Vermont and Delaware, are as transparent with us as they are with each other.

Transparency takes time, as we know. “William Blake saw that we have to pass through innocence into experience in order to arrive, if that’s the right word, at a higher innocence, a place where we bring everything with us…,” says Brown. Yet, Lea answers, “I’ve imagined my mind to have found something that, at least for the fleeting moment, will suffice.” Even a “higher innocence” is no final arrival.

“The universe is slow, really,” Brown says in “Books,” the first of twelve essays. Her description of the tactile experience of reading the printed word transported me to the card catalog at my college library, the slow, insulated suspension so dearly missed, pulling out one drawer that played to another, learning what books to seek out, the titles delicious, fantastic.

Still reading “Books,” I recalled the even slower universe of the grade school library, the wealth inside a pile of library books, the liberty of the card, the stacks, the tables, the quiet. I remembered in second grade, pleading to take out books each week from the “big section,” and when I got permission, reading the same ones over and over, as Brown also did with her childhood favorites.

Then, I remembered an afternoon when Sister So-and-So called me up, pulled out a list of words, and told me to read them. I didn’t know most, but thought I was rattling them off pretty slick, and that she’d be pleased, but she said only, “That will be all,” and tossed the list in her desk drawer as if it were burning her fingers. If I didn’t already know the life-and-death difference a word could make, I knew it then.

This sense, that the world stands on a word, both poets recognize well, and that if you write it’s likely because you figured this out early on. The exchanges in Growing Old compound and deepen this understanding from one section into the next. In “Sports,” Lea tells of a fascinating journey from the high school hockey field, to a struggle with alcohol and substance abuse, and ultimately to writing. He quotes a poem by James Wright wherein the sons of “proud fathers…/grow suicidally beautiful,” whose pain he understands, whose journey can end in “moral idiocy” in those who cannot comprehend it.

“And yet,” he says, “I’m not large, and I know it.” He loves sports, but Brown says, “I’ve written two sports poems…I can pretend.” They are serious, but they have fun. Lea admits, “The feel of improvisation is what juices up my form.” Brown figures, “Poetry is like a large bird, coming in closer and closer until we finally admit we’re stuck with it.” At times reading their serve-and-return feels like listening to a terrific radio program with your favorite hosts, at others sitting down for long conversation with your friends.

But the final, transcending word is for the writer. Poetry feels like “a self-abandonment to something divine…,” Lea says. It comes, says Brown, from “…silence, [it] needs to open itself into silence, not hostage to anything.” That sounds right, and trustworthy, as both poets admit they know a good bit, but still not much completely for sure.

Two poets grown older, still considering, as they do in the introduction, “Are poets’ lives any different in tone or texture from any other sorts of life?” Maybe not. But the particular vocation of the poet, of the writer, I hear them say, is to free words without too much judgment, to judge words without taking them hostage, and to be “eager to continue.” Growing Old in Poetry is an important book and a conversation and a friendship generously recorded.

___

Adrian Koesters is a poet, novelist, and nonfiction writer. Her most recent essays appear in Oakwood Magazine and 1966: A Journal of Creative Nonfiction. She lives in Omaha, Nebraska.