Grand Central Publishing 2011

Grand Central Publishing 2011

My classmate stiffened beneath the warm beam of the spotlight, centered on a curtainless stage in the high school auditorium. Her performance gripped the audience’s attention. She was not alone, however. He leaned ever closer, puckering in anticipation. She was nervous but prepared, as she had announced the previous day, “I’ve been practicing. I kiss my bedpost every morning and every night!” Their lips met, her body suddenly awash with emotion; her first kiss was agonizingly public, a theatrical spectacle bared before the entire student body.

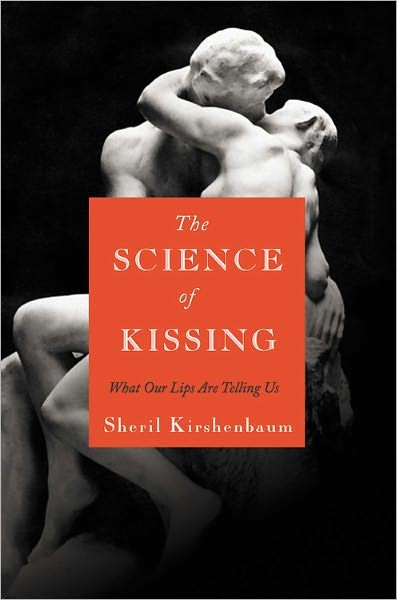

Do you remember your first kiss? I am certain my classmate does. According to research scientist Sheril Kirshenbaum, the first kiss is consistently one of the most memorable events in our lives. The kiss has been an important part of human existence since—well, since forever. A survey of the animal kingdom reveals a multitude of kissing-like behaviors, from the love-bites of lusty lions to the lip locking of the great apes. These analogues to human behavior mirror the osculation (the scientific term for kissing) recorded in the pages of antiquity, from the Hindu Kama Sutra to the Genesis account of the Old Testament.

Though prior research on smooching is spotty, Kirshenbaum compiles a scintillating record of the act. She first attempts to define the kiss—from the tribal “sniff kiss” to friendly and social kisses, to making out with a romantic interest. She probes the annals of psychology and biology to discover why we kiss, and the possibilities are surprising. Kissing might have originated with feeding interchanges between mother and child, laying the emotional framework for kissing as a pleasurable means of establishing and affirming social bonds. Kissing gets us into another’s personal space, close enough to detect odorless chemical messengers that give us clues to our crush’s genetic compatibility. If a first kiss goes sour, it may be our body’s way of saying, “Stop, this isn’t Mr. Right!” Kirshenbaum’s research gets personal as she explores the dark reaches of an MEG imaging machine, “observing [her] soul” on a mass of computer monitors as she seeks to unravel the mysteries of the brain’s response to kissing. We also tour the future of the kiss, from match.com to simulated dating to robotic personal companions.

No work on kissing would be complete without a look into the repulsive side of the kiss, a diagnosis of the cooties—yes, cooties, those disease-causing pathogens that we call germs—that can easily be passed when we swap spit. Kirshenbaum does not hesitate to remind us, though, that romance isn’t lost as risk is outweighed by reward.

While it is definitely not a how-to manual, Kirshenbaum includes ten fact-supported kissing tips, including direction to floss your teeth and kiss often. Ladies, lather on the lip gloss—the shape and color of human lips are tantalizingly seductive. (Notably, none of the tips include practicing on a bedpost or other stationary objects; somehow, the lead in my school play survived her public first kiss, regardless.)

Kissing is a silent language that draws upon a rich heritage of history, biology, psychology, neuroscience, and popular culture, and The Science of Kissing is proof positive that science can indeed be sexy. Kirshenbaum admits that the field of scientific kissing is young and contains more questions than answers, but concludes with this advice: “Don’t give up on romance.” The Science of Kissing is an intriguing scientific text that reads like a novel—a work no good kisser should do without.

—

Cara Carroll is a psychology major and aspiring writer at Austin Peay State University. She has an affinity for the sciences, young adult fiction, and children’s books. She maintains a blog about healthy living

1 comment

Christa Williams says:

Sep 19, 2014

Very well written! As my husband and I are compiling notes on a marriage book, we will certainly pick this one up to supplement our experiences . . . and perhaps to add to those as well.