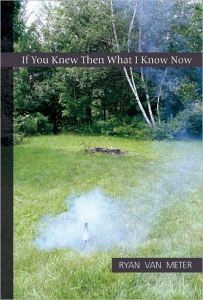

The two required texts in the fall 2011 creative nonfiction writing course I taught at St. Lawrence University were the Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction (Touchstone, 2007) and Ryan Van Meter’s essay collection If You Knew Then What I Know Now (Sarabande Books, 2011). I contacted Ryan, asking if he’d be willing to participate in the class’s study of his work by answering students’ questions via e-mail, which he generously agreed to do.

The two required texts in the fall 2011 creative nonfiction writing course I taught at St. Lawrence University were the Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction (Touchstone, 2007) and Ryan Van Meter’s essay collection If You Knew Then What I Know Now (Sarabande Books, 2011). I contacted Ryan, asking if he’d be willing to participate in the class’s study of his work by answering students’ questions via e-mail, which he generously agreed to do.

Before students submitted their questions, they read two interviews with Ryan, one that appeared in Bookslut and one I conducted for Metawritings: Toward a Theory of Nonfiction (University of Iowa Press, forthcoming 2012), so they could get a sense of the questions he had already addressed as well as how to approach writers in interviews.

I sent Ryan’s answers to the students to read before the next class, and when we came back together, I projected each answer onto a large screen so we might measure his ideas and approaches to writing against our own study of creative nonfiction, as well as our own writing.

Ryan Van Meter’s If You Knew Then What I Know Now is featured in New York Magazine‘s The Year in Books and The Millions’ Year in Reading. His work has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, The Iowa Review, The Normal School magazine, Ninth Letter and Fourth Genre, among others, and has been selected for anthologies including Best American Essays 2009. He holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from the University of Iowa and teaches at the University of San Francisco.

Q: Why did you choose the essay “If You Knew Then What I Know Now” as the namesake title for your collection?

RV: Of all of the essays in the book, this one was the first I wrote; it was specifically inspired by a Julie Orringer short story (from her excellent collection How to Breathe Underwater) titled “Notes to a Sixth Grade Self.” Even months after the reunion, I couldn’t believe this guy had actually apologized to me. Couldn’t believe this guy apologized, but also couldn’t believe in the contrived perfection of the neatness of a bully apologizing to his nerd at a reunion. It’s basically a Lifetime movie. But it was with that apology in mind that I couldn’t stop thinking about the original terrible moment at Mark’s house, how in some ways it had been worth all its pain because of the apology.

So it became the title of the whole book because so much of the collection is about looking back to pivotal, transformative moments from the point of view of later understanding or revelation. In other words, all those awkward, embarrassing moments were also worth something – they were, in a strange way, gifts. In all of the essays, I strove to create a sense of generosity for all of the characters, even the antagonists, especially the bullies. That narrative sense of encompassing sympathy felt most succinctly encapsulated by this essay’s title.

Q: While you were writing these pieces, did you ever have the intention for your writing to make anyone confront you or help people you knew understand you better, or did you write with a broader audience in mind?

RV: I try not to think too much about audience when I’m writing. (Audience is a publishing concern; being good at writing and being good at publishing are entirely different skills.) I think no matter who is writing or what you’re writing, we all strive to reach as many good readers of our work as we can find. Or that our work can find. I tried to make these experiences as universal as possible – to simultaneously feel authentic or to “ring true” but also to be surprising, revealing, offering something new. I never thought of an essay as a mode of starting a conversation with a particular person from my past. When I imagine an essay trying to do that, I can’t see how it would appeal to any other reader besides that one person, so then, why not just send that person a message via Facebook?

Q: Regarding memory vs. truth in creative nonfiction: Where do you draw the line between pure documentation of truth and manipulating the truth for the benefit of your point in the story? When is it permissible to change details when telling a story? How difficult is it to remember the details and, more importantly, how you thought and viewed the world at different times in your life, especially when writing from the perspective of a very young child? Did you keep a journal?

RV: I don’t know anything about neuroscience, but my hypothesis is that the imagination and the memory reside in the same fold of our brains. It might even be the case that we use one to access the other – that in order to claim something from the filing cabinet of memory, we use the imagination to pull open the drawer. So I don’t get hung up on whether some detail I “remember” is the literal truth from when I was five years old. You have to trust yourself. And you have to recognize that getting uptight about the rigid truth of details during composing (the first impulse of writing) is a terrific way to put a big obstacle in your way or to stop the writing altogether.

But back to trusting yourself. If you’re writing about an experience from when you were five years old, of course you don’t remember entire conversations or what your mother was wearing on some Tuesday. But in the service of the reader, you create from your paltry memory a re-imagining of the experience. (Which is not the same thing as making up a jail sentence you didn’t serve as a way to make yourself seem like a badass.) You put yourself back in the moment. That’s your whole job. You might not remember exactly what your mother said on that one day, but you know how she talked. You don’t remember what she was wearing that day, but you know how she dressed. If you only remember one thing, say one object, then you use that one thing to put the rest of the scene together (or back together.) Picture it in your mind, in all its detail, then just look to the left of it and write down what’s there. Then look to the left of that, and on.

And sometimes, for the sake of the story, you have to change or alter certain truths. You have to ignore that there were other people present in an experience because they weren’t essential to the action and the reader doesn’t want to keep up with all the names. You have to conflate two very similar days for the pacing, because to the reader, there’s no consequence of collapsing that time. I don’t think we’re allowed to make up anything, or make any change that is a verifiable fact that could be looked up somewhere. But if you’re making decisions for the sake of the reader’s ease with the story, then I think it’s allowed.

I do have a pretty competent memory, and I have kept a journal at certain points in my life, but I didn’t refer to any of them in creating this collection, with the exception of “Things I Will Want to Tell You.” I hadn’t written in a journal in years, but at a therapist’s suggestion, I started writing about that experience, and in one weekend, I filled 40 pages, front and back.

Q: A question about endings: At the end of the essay “Cherry Bars,” when you and Angie are ducking down in her car to avoid being seen by Claire and Kevin, you conclude the essay with them nearing the car, without explaining what happens. Do Claire and Kevin discover the two of you, and if so what comes of it, or were you somehow able to go through with the cherry bar sabotage?

RV: Oh, yes, they discovered us, cherry-red handed, so to speak, and no, we never did get the chance to commit vandalism by way of dessert. Which is probably fortunate for all involved. But your question raises an interesting point about endings. Just as I prefer writing beginnings of essays with the action already in motion, I like creating endings that simultaneously satisfy the reader while opening (or leaving open) new possibilities. Some combination of “life goes on” and “this part is over.”

In my writing classes, we call the ending that tries too hard to wrap up and create closure the “All in all, it was a really weird summer” sentence. After a semester with me, my students can recite “All in all…” in unison on command. I try to encourage in them a phobia of that kind of ending. The ending of “Cherry Bars” ends the “story” of that particular afternoon, but hopefully also hints at trouble still to come, years ahead. The final sentence also contains the same gesture (turning off music) as the first sentence, which hopefully achieves another kind of closure.

Q. Could you offer tips on writing essays about your life and not allowing the narrative to wander?

RV: I actually think you need to allow yourself to wander when you’re writing. You have to bump into things, stumble over a forgotten memory or some aspect of the experience you didn’t even know was there. I’m a big fan and proponent of free-writing. I hardly ever know where I’m going when I start something; I just sit down with an empty notebook and start writing as fast as I can. After I’ve gathered a lot of pages, and have found an opening section, a first sentence that exemplifies the voice and introduces the “problem” of the essay, I start transcribing to the computer (and voila! your “first” draft is already your second!). When I’m working in a Word document, that’s when I start asking, “What is this essay about?” or “What is the focus here?” It’s only after you have the structure and the direction and the details that you start discovering the insight that will surprise you. If there’s nothing in your essay that surprises you, how could it ever surprise the reader?

Once you know what your essay is about, that’s when you go back and cross out anything that doesn’t belong, which makes it look focused. That’s the trick: Stumbling around until you get somewhere interesting and then covering your tracks so it looks as though you knew what you were doing the whole time.

—

Jill Talbot is the editor of Metawritings: Toward a Theory of Nonfiction (University of Iowa Press, forthcoming spring 2012). She is the author of Loaded: Women and Addiction (Seal, 2007) and the co-editor of The Art of Friction: Where (Non) Fictions Come Together (University of Texas Press, 2008). Her work has appeared in Under the Sun, Cimarron Review, Notre Dame Review and Ecotone, among others. She teaches at St. Lawrence University, in northern New York.