Nonfiction, in the tradition of the personal essay, is a wandering expression of ideas, a memory here and a dreamscape there. But how do you begin the composition process? Moreover, how can you organize your ideas and establish a strong workflow? Years ago, I came across a YouTube video in which an instructor (I don’t recall their name), standing before a lecture hall of undergraduates, stated that writing is, above all else, a computational process.

Nonfiction, in the tradition of the personal essay, is a wandering expression of ideas, a memory here and a dreamscape there. But how do you begin the composition process? Moreover, how can you organize your ideas and establish a strong workflow? Years ago, I came across a YouTube video in which an instructor (I don’t recall their name), standing before a lecture hall of undergraduates, stated that writing is, above all else, a computational process.

The instructor advocated embarking on the writing process immediately, concurrent with starting our research. This generative/improvisational technique—think jazz ensemble performance— allows the writing process itself to “calculate” the direction of our work and to generate momentum. In short, the very act of writing reveals our subject, little by little. As the piece progresses, we can determine how to incorporate our research into the narrative, making it readable and relevant. Moreover, the computational process helps reveal gaps in our research, highlighting areas that need further investigation.

Now, let’s explore three practices that will help you to begin.

1. Maintain Commonplace Notebooks

In its most basic format, this notebook is used to record various ideas and quotes from your reading and research. Depending on your method of indexing, the notebook might become something of a self-created reference work. It is an aide to memory that the writer can use to great effect. One of the most helpful articles I found on the subject is by Sam Dolbear. In the May 8, 2019, issue of The Public Domain Review, he writes:

“Popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a ‘commonplace book’ was a notebook used to gather quotes and excerpts from one’s literary wanderings—a kind of personalized encyclopedia of quotations. In ‘A Letter of Advice to a Young Poet’ from 1721, Jonathan Swift remarked that a commonplace book is something that ‘a provident poet cannot subsist without, for this proverbial reason, that great wits have short memories.’”

Perhaps the most famous example of commonplace notetaking comes from John Locke, the philosopher and political thinker who developed a well-regarded method. Dolbear goes on to explain Locke’s notetaking innovations in great detail. (See list below for further reading.)

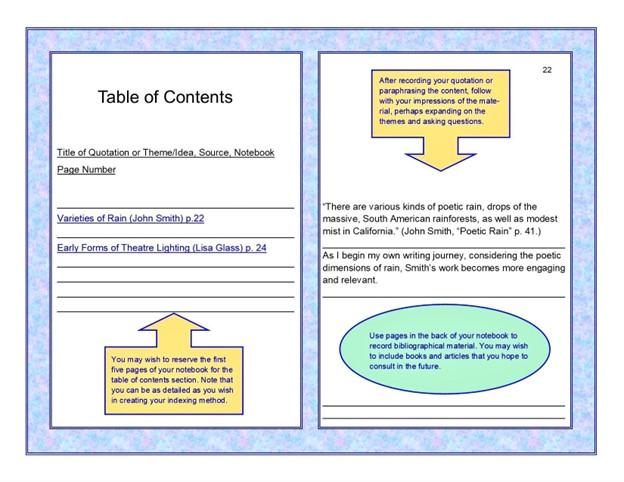

Here is the notebook model I have designed for my own use:

Whatever method one employs, creating your own encyclopedia of themes and ideas is a useful first step in generating computations. As you continue with a daily practice, your techniques and methods—and your concurrent writing—will develop accordingly.

2. Create Collages

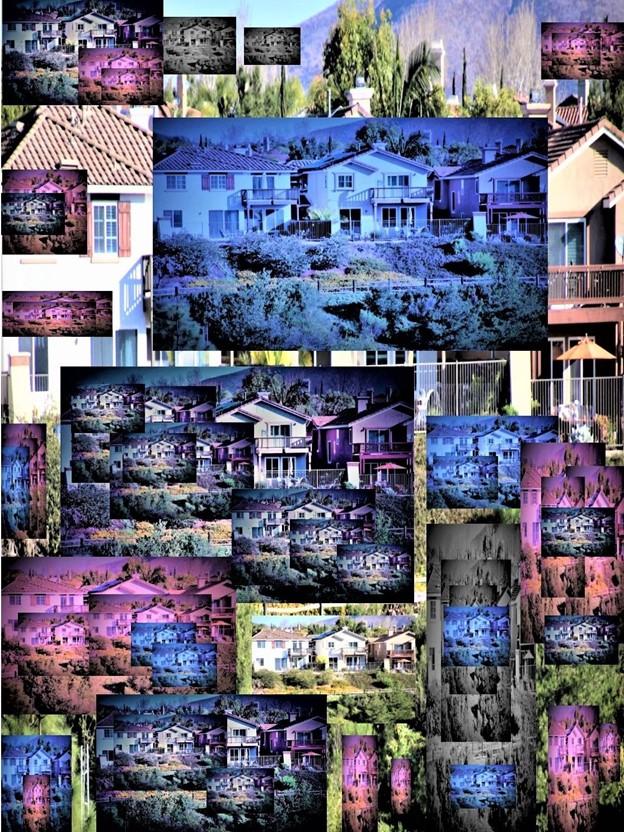

Another method that enriches my writing practice involves visual art, either adding hand-drawn elements to my notebooks or, most frequently, creating collages. The latter has enabled me to add graphic elements to blog articles and books. Here’s the fun part: Both analog and digital methods apply, whichever the writer prefers. You may wish to assemble paper collages, which can become art pieces in their own right. Or, for electronic media, consider the use of digital collages. Here, Adobe Illustrator can be helpful. Compiling a set of commonplace images is incredibly inspiring, providing us with thinking tools as we embark upon the writing process. Below, you will find the collage I created while researching the history of subdivisions in California.

Here, I took a single photo and created multiple images of varying sizes and colors, adjusting light levels for different effects. In addition to providing a graphic element for the essay, the project helped me think about the unique lives and experiences that unfold in the blandness of the suburbs. From there, I began to record examples of this theme in my commonplace notebook, incorporating biographies and case studies into the emerging narrative. And this brings us to our third item:

3. Begin Writing Your Piece in the Notebook

As the notebook provides you with a safe space to experiment and develop ideas, consider beginning your article, essay or book within its pages. As you write, feel free to add copious margin notes, ask questions, and jot ideas for additional research and analysis.

Computations Continue . . .

The computational process is ongoing, inspiring you to think in new directions, helping you to refine ideas and record important information. With that in mind, use it to continue the writing process, day by day. Over time, you will discover that narratives reveal themselves in rich and unanticipated ways.

For Further Reading:

Bestvater, Laurie. The Living Page, Keeping Notebooks with Charlotte Mason (Underpinning Press, 2013—place of publication not specified).

Dolbear, Sam. “John Locke’s Method for Common-Place-Books” (The Public Domain Review, May 8, 2019).

Schwiebert, John. Reading and Writing from Literature (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co., 2005).

___

A. M. Palmer is a writer, graphic designer, and retired park ranger with work appearing in Belle Ombre, Adelaide Literary Magazine, Dissident Voice, and other publications. Inroads: An Urban Park Anthology is the author’s first book. Palmer holds a master’s degree in history from the University of San Diego and continues to research art and social history with a variety of upcoming projects. The author is a member of the National Association of Independent Writers and Editors.