A key element of the scientific process is play. This is often overlooked. When I say play, I mean the kind of game that might end with everyone crying. The suspense, risks, hope, joy, and dead ends of making hypotheses, forging wilderness, and running experiments are messy. Wonder fuels inquiry and, often, human connection sustains it. What we read about science usually leaves out these cultural and emotional landscapes. To harness and incorporate humanity into our stories about science, we can use both creative process and craft.

A key element of the scientific process is play. This is often overlooked. When I say play, I mean the kind of game that might end with everyone crying. The suspense, risks, hope, joy, and dead ends of making hypotheses, forging wilderness, and running experiments are messy. Wonder fuels inquiry and, often, human connection sustains it. What we read about science usually leaves out these cultural and emotional landscapes. To harness and incorporate humanity into our stories about science, we can use both creative process and craft.

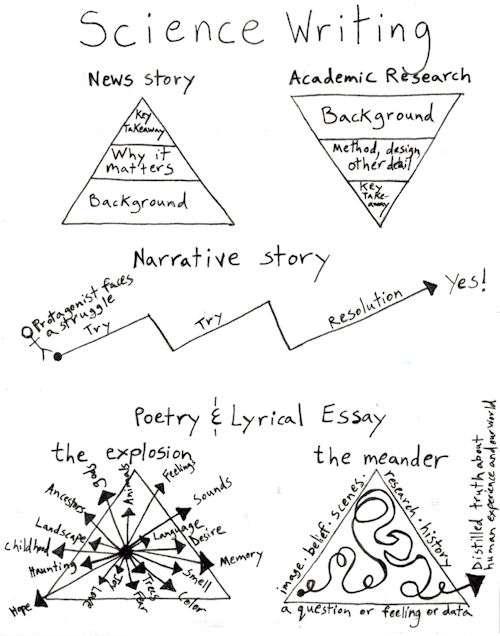

Most science comes to us in news articles that hook readers in the first lines. For details, turn to page fifteen. The hierarchy of information forms a triangle structure anticipating limited attention.

For academic research the template is univocal. Papers start with the background. Punchlines come at the end. Methods and data sit heavy in the middle, making investigations reproducible. This structure strips out the human element of improvisation and ambiguity. In precision, we lose some truths. Essays, memoir, poems, and literary writing can animate the picture and reveal complexities. This, in turn, allows for exploration of questions beyond what science can answer.

I’m in the editorial process of a book of essays I’ve written about being a climate scientist and going to work in politics. I started with a traditional narrative: a problem needs to be solved, the hero tries and fails, the hero has a breakthrough, everything is better. But I haven’t solved climate change—research is incremental. My drama is the attempt to translate nature into science and science into political action. To capture this effectively, I had to let the essays take other shapes.

In Jane Alison’s 2020 Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative, she writes, “Narratives that strike me as radial [explosive] are those in which a powerful center holds the fictional world—characters’ obsessions, incident in time—tightly in its gravitational force.” Alison focuses on fiction, but science writing requires narrative tools too. I foreshadow, develop characters, and paint scenes. In an essay about peeing, the narrative forms a radial. Far from a meritocracy, science expeditions exclude all but the able bodied who can pee standing up. Like a canoe weathering the wake of an unaware speedboat, the mundane fact of my female body posed challenges over and over in the field. Writing about these challenges, dark humor and innovation explode on the page, combining frustration and triumph.

To open the Federal Bureau of Investigation Laboratories to readers, I world-build in the same way I would for a story about mermaids. In an underwater city, a sea witch dilemma might be discussed by friends over kelp burritos. Similarly, I relate the world the reader knows to the FBI with a lunchtime conversation in the Laboratory’s cafeteria. Over grilled cheese made with Kraft singles, colleagues discuss research to identify the molecules that make up the the scent dogs track to find dead bodies. Going into the laboratory, I compare the size and sound of instruments to dishwashers, microwaves, and other familiar machines.

To open the Federal Bureau of Investigation Laboratories to readers, I world-build in the same way I would for a story about mermaids. In an underwater city, a sea witch dilemma might be discussed by friends over kelp burritos. Similarly, I relate the world the reader knows to the FBI with a lunchtime conversation in the Laboratory’s cafeteria. Over grilled cheese made with Kraft singles, colleagues discuss research to identify the molecules that make up the the scent dogs track to find dead bodies. Going into the laboratory, I compare the size and sound of instruments to dishwashers, microwaves, and other familiar machines.

Alison believes our bodies recognize “fundamental patterns in nature.” She discusses meanders, cells, waves, spirals, and fractals as other structures for our stories. My hypothesis is that writing—or reading—with these forms in mind push us into states of unknowing. I like to start writing classes by building a sculpture with shoes, bottles, paper towel rolls, or whatever is around. I ask students to draw without looking at the page. This leads to lots of laughter. Often, we draw (or write) from our mind as much or more than from the actual world. Similarly, the Dance Your PhD competition run by the magazine Science forces articulation of complex research through movement. Unfamiliar approaches bewilder, and sometimes disorientation clarifies our truths.

Experiences are not neat. Our brains don’t work linearly. To write, aim the camera and decide what is in and out of the frame. But first, look around. Sometimes a state of flow gives us clay that won’t find form until the revision process. Steven King urges to “Write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open.” Even if a writer’s goal is chronological, the creative process may need to stretch, burst, break apart, replicate, and divide.

Alison tells us to “look at text close-up: how it feels to travel word-by-word as the narrative unfurls around you.” I have students circle the verbs from Observed Changes in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. The action in the first page includes: what has been, was, is, average, show, and produce. Next, we circle the verbs in the prologue to Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dream where action calls, stops, slumps, drives, clinks, and cranks. Disembodied from the sentence, the verbs in the climate report don’t invoke our senses while the clinks and cranks of young Einstein resonate in our body. This exercise makes visible the passive voice and invisible actors in conventional science writing. Trained in academics, my first drafts, written behind closed doors, show this heavy imprint. I’ve learned to meet myself halfway. Words come as they will, and I choose what I do with them in revision.

Another way to loosen technical grooves is with erasure poems. With a sharpie, black out all but a few words, distilling the message. Like an experiment done at different temperatures, the composition of the precipitate changes with mood. From the same 240 words of my dissertation in Earth Sciences, I create:

Abstract goals reflect automated values

And,

Approach to value flow

As I edit my book and view pages as a reader, I step through the looking glass. One of my essays is structured like the cells in a blade of grass. Like the repeating brick shape of cells, each section is an attempt to storm the political stage, sometimes garnering attention for the wrong reasons. I can’t control if the reader sees the essay’s bright chloroplast. The book will live its own life once it goes out to bookstores and libraries.

Throughout the pandemic, I worked next to a shelf of books from a public art instillation I did on our relationship to nature. The books hold the ghosts of hundreds of hands hovered over the page with shared pencils looping letters into a single weave. Visitors list words, compose haikus, share stories, jot breathless phrases, and sustain rhymes. All this carries life onto the page. Life that buoyed me in isolation.

There is no fashion contest for extravagant story structures—visualizing the shape of our writing is no more than an invitation to play. It is a tool meant to let direction well up from the writer or to give the reader momentum. The shape of this essay is a wave cresting and folding back into ocean foam. It ends close to where it started but leaves the reader in a hallway of open doors.

___

Anna Farro Henderson (previously published under E.A. Farro) has a book of essays forthcoming in 2024 about being a climate scientist and going to work in politics. She teaches creative writing at The Loft Literary Center and lives near the Mississippi River with her family in Minnesota.

4 comments

Amanda Le Rougetel says:

Jan 24, 2023

“Disembodied from the sentence, the verbs in the climate report don’t invoke our senses while the clinks and cranks of young Einstein resonate in our body.” What a creative and powerful way to ‘show not tell’ the impact of the passive voice in writing. I love it.

During my master’s program in applied communication, I became increasingly frustrated with how dense and obtuse so many of the required readings were. So I researched ‘discourse conventions’ and wrote a paper on how these changed when a specific scientific research paper was transformed into a journalistic article in a national newspaper. My own wonder certainly fuelled my inquiry and, while this maybe isn’t the usual definition of ‘play’, I experienced so much discovery and reward in the process (and maybe a few tears, too), that I loved the process.

It was fascinating and rewarding, and I carry the value of this learning-through-discovery with me, still, almost two decades later.

Anna Farro Henderson says:

Jan 25, 2023

Thank you for your comment. What a beautiful story of play – discovery and inquiry and learning.

Vince Higgins says:

Aug 29, 2023

I have attempted to read several of these Craft Essay’s and found them difficult. Yours started out compelling, then started to drag. I assure you, it’s probably me. What captivated me here at first was your discussion on writing about science. I have a science background myself, and my writing style reflects it. Even in some of the fiction I have written the comments are often about technicality in the narrative giving some readers pause. While my background is in engineering and I had a very diverse career that spanned multiple technical disciplines, my current focus in retirement is environmental science. That drew me in as well.

You then turn to doing what the others do in describing the writing craft and start discussing stye, in very stylistic ways. As you have probably noticed by now my style is very Joe Friday; “just the facts mam”. I can use humor and that helps, though it tends to be rather dry at times.

My essays (never been published) are largely on science literacy, and countering science denialism. These are existential concerns both globally and personally.

Kim Perez says:

May 23, 2024

What a great essay! Fun to read and practical too. Thank you for sharing your insights. I’m looking forward to reading your book.