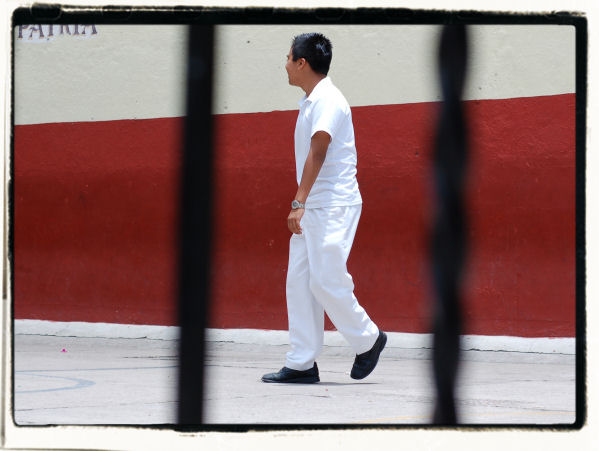

Joe steps forward and back, holding his imaginary foil as the instructor barks commands. Joe’s face is a mask of concentration and anxiety, his body tense. For Joe, it is important his moves are just right, important the teacher say to him, “Good job,” at the close of class.

Joe is eleven. We have moved five times in this span – more from necessity than choice – and unlike his dad or his nine-year-old sister, Joe and I are less successful at the art of starting over. But at each new house, brochures arrive from whatever community center or YMCA lies nearby, and Joe and I read through course descriptions, age requirements and equipment needs, deciding what he’ll dabble in that year to distract himself from what he’s left behind. It hasn’t worked quite yet.

Joe has taken to the fencing instructor, though, who’s both gruff and funny, and whose thick, Massachusetts accent we laughingly try to imitate on our drive home after class. But while the instructor yells jokes as often as he yells commands, Joe thinks his only defense in life is perfection, and he’s hesitant during class, easy to rattle. From my metal folding chair at the far end of the gym, I can see the straight line of Joe’s mouth as he and another boy spar with their imaginary foils. Joe messes up and he wants to start over, but the instructor says no, keep going. I will him to relax, not care so much, but I’m sitting on my hands, my stomach tight. I’m no good at this either.

Joe and I are tired of being economic vagabonds, tired of negotiating another new town, new job, new school. Next year, I hope we will be busy with friends and cookouts and Little League games, and we’ll have a hard time remembering the feeling we didn’t belong. We will talk about Oklahoma and Ohio and Nebraska and North Carolina as if they are ancient history, and all we went through to get here will seem providential, meant to be. But next year is not here yet.

The class ends, and Joe’s instructor points to him, saying, “Good job.” This puts a grin on Joe’s face, and I smile as well. On the way to the car, I ask Joe about the teacher’s commands, which I hadn’t understood.

“How did it go? Advance, lunge, retreat?” I ask.

“No,” Joe says. “It’s advance, retreat, lunge, recover.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” I say. “Why would you retreat before you lunge?

“It’s like a trick,” Joe says. “You retreat to get the other guy to come forward.”

“Then you stab him?”

“You don’t stab him, Mom, you engage him,” Joe says. “Or attack. But we haven’t learned that part yet.”

“Maybe that’ll come when you start with the real swords.”

Joe rolls his eyes at my feigned ignorance and reminds me they’re called foils. Then he says he wants to sign up again for spring. I’m surprised, since he’s never done anything twice before. I say yes.

That night, I get on the computer in a haphazard attempt to educate myself on the language of fencing—attack, engage, disengage, parry. Riposte, beat, derobement, remise. Clearly, “Advance, retreat, lunge, recover,” is just the beginning for both of us.

Next year, when my husband inevitably shares the news his employer is downsizing or his boss is incorrigible or he’s maxed out his potential and we need to move on—because the world he works in never ceases to spin off center—we will sit in the living room after the kids go to bed and map out various scenarios while fighting our fears of being rudderless and lost yet again. Next year I will need to remember the look in Joe’s eyes every time he faces fall in a new school, every time he sizes up a new neighborhood, looking out our living room window at boys going by on skateboards and bikes, wondering who, if anyone, will end up as his friend. I will think of that combination of fear and anxiety and determination and weariness and remember how much this takes out of Joe, out of me, out of all of us. Next year, I tell myself, we will find a way to stay.

Kate Flaherty’s essays have appeared in Brevity, Fourth Genre, Creative Nonfiction, and elsewhere, and she regularly blogs for the University of Nebraska Press: http://nebraskapress.typepad.com.

photo by Dinty W. Moore