Late October, 1969. I’m three years old. We’re driving at night on a country road outside Culpeper, Virginia, to visit my recently widowed grandmother. No moon or lights. We have only the reach of the high beams to see by. I sit between my parents in the front seat. My mother is six months pregnant with my sister, and my father is driving a Mercury Comet Wagon, the car my mother has said is cursed. It had belonged to her father, and one of the last things he’d ever said to her was, “Don’t think you’re going to get that red car.”

My parents have moved to the Blue Ridge Mountains hoping for a quiet place to raise a family. They teach at a boarding school in the foothills, tucked behind fences inside twelve hundred acres of gently sloping lawn. But the week before, as she turned away to unload groceries by our house, I released the emergency brake and climbed out just before the car started to roll, down the hill and into a tree. I couldn’t have known what I was doing, mirroring my parents, my mind still free of consequence. Only this afternoon my father got the Mercury out of the shop.

Now he’s gripping the wheel with both hands; my mother pulls me closer, clear of the gearshift. It’s warm for late October. Our two dogs pace in the back and rest their chins on top of our seats; their breath stirs the close air. As we round another curve, my father rolls down his window, letting a breeze into the quiet cocoon of our car. Do you hear something, he says and begins to slow down.

The glass explodes in front of me. Loud snaps and a deep bellow. Then I’m looking at a mass of black fur and bone where our windshield used to be. I reach for my face and everything is wet, tiny shards dug into my hands and arms. I’m so stunned by the world crashing in that I can’t scream or cry or move.

Even as my parents grab me, stumble out with the dogs and head for the light of a farmer’s house nearby, I remain suspended in my own disbelief. Inside, my father calls an ambulance. I’m so perfectly still in my mother’s arms that she is too afraid to see what has happened. She goes into the bathroom, turns on the light, and holds me up to the mirror. It’s the only way she can bear to look. In the reflection I am covered in blood and stray tufts of Angus fur. But my eyes are wide open, because what my mother doesn’t know is that I am looking at me, too, in the very moment of my first memory, where the curse of the conscious world begins.

Porter Shreve is the author of two novels: The Obituary Writer and Drives Like a Dream. He is co-editor of several literary anthologies and his work has appeared in Witness, Northwest Review, the Chicago Tribune, and the Boston Globe. He currently directs the Creative Writing Program at Purdue University.

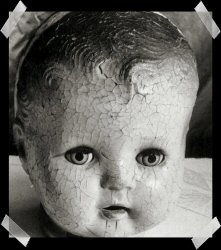

Photo by Dinty W. Moore