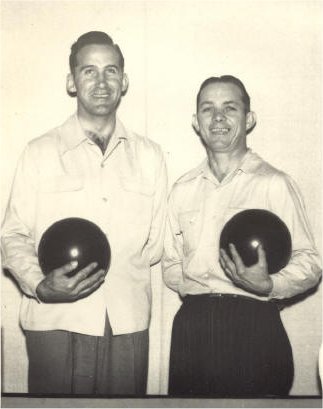

I remember my father with his pot belly, polishing his bowling ball, standing on the lane, taking a deep breath, getting ready to swing his arm back and then forward. I never told my father how beautiful he looked and how grateful I was that when he threw a strike, he always turned around to see the audience. He looked relieved when he saw that I was there.

When my mother worked nights, my father would take us to the bowling alley. Once I remember seeing men fighting in the bowling alley after someone missed his spare, causing him to lose his game. He had no money to pay his debt. I asked my father why no one seemed to be calling the police. My father looked at me and said, “Everyone knows that man deserves to be beaten. He didn’t do what he set out to do.”

It always amazed me that my father had so much confidence, as if he always did what he set out to do. Even if he had a particularly hard spare, he’d announce to his partner: “You better be prepared to win this one. I’m going to nail those pins.” When he missed, he looked up at the ceiling, shocked that such a thing could happen, and then cursed the lanes. I loved that he never found fault with himself.

I took everything personally which caused me to throw my game more often than not. Eventually, I quit bowling and pursued acting in the school plays. They often made me student director, denying me a role, making me the gopher, fetching coffee, writing down the blocking. My father rarely went to see the plays I wanted to be in.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “Plays aren’t my thing. I just thought you had real talent as a bowler. In fact, I know you did. You could have probably became professional.”

My father loved to arrive at the bowling alley when it first opened at 9 a.m. We would watch huge wax machines painstakingly move across the lanes, coating them with a thick gloss. They almost looked heavenly in the way that they reflected light. I never got close enough, but I bet I could have seen my own reflection. Cleanliness always impressed me, having grown up in a trailer park. The idea that someone would go to such lengths to make something so tidy for a sport intrigued me.

Everyone seemed to smoke in the bowling alley. My brother and I would pick up the cigarette packs people left behind and go into the bathroom and light up. We’d compliment each other on how mature we looked, and we did look cool, older. Outside the bathroom, we’d hover around the chain smokers. When they tried to be considerate and blow their smoke in the opposite direction, we’d beg them to be rude. We’d beg them to let us have a drag. They usually acquiesced after they laughed at our admiration of them.

My brother was so small that he often sat in the trophy case. The trophy case was pretty big and was placed where people bought their shoes. The woman who worked there was like another mother to us. When someone didn’t know what size they wore, the woman asked my brother. From behind the glass of the case, he pushed his head as close as he could to the person’s feet and guessed a size. He was usually right. He looked so cute behind the glass, protected from the more adult sounds of pins crashing. I liked knowing that he was safe from mature collisions.

Perhaps bowling is why I became such a nervous person. The first sound I recall is the shattering of pins, the sound of them ricocheting off one another. I remember going outside after spending the day in the alley and being shocked and disturbed by the silence, almost angry that God would create an alternate world, one without the noise that drowned out my own anxieties.

Steve Fellner’s essays have appeared in Cimarron Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Northwest Review, North American Review, among others. He has completed an as-of-yet unpublished memoir entitled Where I Went Wrong.