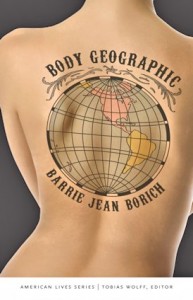

This interview was prepared by Linda Avery, Polly Moore, Jan Shoemaker, and Aimee Young (current nonfiction students in the Ashland University MFA program, Bonnie J. Rough’s Spring 2013 section) with questions exploring the memoir, Body Geographic.

This interview was prepared by Linda Avery, Polly Moore, Jan Shoemaker, and Aimee Young (current nonfiction students in the Ashland University MFA program, Bonnie J. Rough’s Spring 2013 section) with questions exploring the memoir, Body Geographic.

PM: Your voice in this book is so wise, so at peace with all the different parts of you that make up you. I marveled at your ability to be transparent when you could have “chickened out” or glossed over details. There’s fairly vivid lovemaking with Linnea, your beloved role of Auntie to Adria, a conference threesome, hanging with the drag kings, falling down drunk, and also Barrie the daughter, the granddaughter, the sister. Did writing this book feel like an act of courage? Did you have conversations with loved ones prior to publication, and have you encountered issues resulting from your transparency since the book came out?

Borich: For as long as I’ve published, readers have asked if my writing feels to me to be an act of courage. The question sometimes pleases me, as it suggests I’ve succeeded in reaching at least some readers in a primal or urgent manner, but in truth I rarely feel particularly brave while writing. I’m often afraid, especially if failing to engage with the page. Or frustrated. Or on better days, intensely, intuitively focused. I might feel bold, or funny, or furious. But courageous feels to me a word that doesn’t quite fit the writing process, perhaps because when I’m really writing the work itself is leading the charge.

Some of this is cultural in that many of the subjects you list here—lovemaking or drinking or gender performance—are part of the daily parlance of worlds I’ve been a part of for many years. I came of age as an artist in both the queer arts world and the queer sober world of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, so transparency, as you put it, about issues of sexuality and identity and addiction is normal to me. Even though the presence of these worlds is more common in mainstream venues than it once was, still these subjects are much less muffled in the LGBTQ worlds and I can think of a dozen queer artists off the top of my head whose works are more explicit than mine.

What you notice in my work is likely the symbiosis of my communities, my particular voice and my own quirky ways of executing craft. When I’m actually writing I’m not thinking about courage or edge or consequence, and I don’t check out what I’m doing with anyone but my spouse Linnea (who is usually my first reader) and even she doesn’t have veto power, just an open invitation to challenge me. More to the point, as a writer, whatever my subject, I value precise and embodied language. When I’m working I’m thinking first about bringing experience to language, about visceral rendering, about surprising myself by what I discover on and from the page. As with any writer, this all comes to me one word at a time.

LA: What stood out most to me as I read Body Geographic was the originality of its structure and your ability to connect your own life story and family history with the geography of maps and places. About the project, you’ve written: “I came to consider my book a variety of map art–my own quirky attempt at counter-mapping my American body against the ‘true and accurate atlas’ any woman of my place and generation was supposed to follow.” Your use of maps and geography to do this is extremely unique. What were your difficulties in translating maps into language?

BJB: I wouldn’t say that in Body Geographic I’ve translated maps into language but rather that the process occurred the other way around, that I translated language and story into maps. At first all I meant to do was braid story fragments about place and the body that I felt belonged together—most significantly, my family’s immigration story and my own migration to queer identity story. My first title for this book was This New World from a line in the Philip Levine poem “The New World” —Full-figured women in their negligees/streamed into the streets from the dark doorways/ to demand in Polish or Armenian/ the ripened offerings of this new world. I wasn’t thinking of maps at the start. I’m not sure moving from form to subject works very often; in my experience form rises out of subject. From the start of this project my aim was to bring these two personal migration narratives together, to intertwine them in some way around the ideas of place, movement, and change.

The map form came to me in process (I don’t remember precisely when) after I’d come to the idea of the book being a kind of “female geography” with place as my primary lens through which to look at interlocking kinds of American experience. The first move toward maps came with the inclusion of the “insets.” Somewhere along the line, in the process of revision, I tried to reconfigure the fragments as a main text interrupted by these close-up views. I wish I could recall what led me to this move, but the moment of invention is lost to me. All I remember is that I was so attracted to and inspired by the structural shift that I followed the impulse, eventually realizing I considered each essay a kind of map, and then challenging myself to make sure my use of the map-as-form was not too facile. So what then, I asked myself, do I mean when I call these essays maps? What do I need to research, discover, and revise toward in order to make this map form meaningful and integral to the project?

PM: I loved how you were able to interweave your love of geography and your strong connection to place in Body Geographic by structuring your story as a map with overlays, underlays and insets. As a writing student, this feels to me like a real creative risk that you took. As writers, how do we know if the nontraditional, “quirky” idea will pay off or fall flat, preventing a beautiful story from getting “out there”?

BJB: I wish I had better news here, but the truth is we never know if a risk will pay off. If we did, then risk wouldn’t be so risky, right? All we can ever do is attempt. I remember clearly the moment when one of my writing professors revealed the Montaignian root of the word “essay” meaning to attempt or try, a lesson I’ve repeated in every nonfiction writing class I’ve taught since. This understanding may be the single most important motivator of anything I’ve written, this permission to attempt what I don’t yet know how to do or feel or think.

Structure is simply part of this larger essaying endeavor for me. I will attempt, and most of the time I will fail, but I attempt again, and hopefully (to borrow Zadie Smith’s language) I will fail better the next time, until finally I find the movement or change within the work that, to my ear, justifies the form.

Plenty of publishers passed on this book because they found the nonlinear form an unnecessary distraction. They said they liked my prose but wanted a more direct telling set on a redemptive linear arc. Such books sell better and are more widely read; I get it. And familiar chronological structure can be beautiful if executed with skill and avoidance of cliché and sentimentality. Sometimes I wish I did write that way because then perhaps I’d get to stay home and write all day everyday and make lots of money, but alas, I just don’t have any fire to write those kinds of books. This seems to be a born-this-way situation for me; narrative risk is a requisite part of my process.

AY: In “The Craft of Writing Queer,”(Brevity, September 2012) you urged the synthesis of “queerish content” with “queerish form.” Will you discuss what this meant for you as you wrote Body Geographic? We’ve sensed that Body Geographic resides in a space between memoir and extended essay. Do you see the book sitting nearer to one form or the other? What does this in-between space allow a writer to do? What are its risks? As you wrote, did you envision a particular audience?

BJB: I often think the most queer thing about my work is not content but form, in that I can only seem to write in ways that break the normative linear mode. Not that one has to be “a queer” to write a nonlinear narrative, but I do think my ways of inhabiting form and voice are related to my life in that I don’t inhabit a socially normative community, family, or marriage and thus the forms within which I experience the world are themselves not the formal norm. Queers are now less “queer” than we were when I wrote My Lesbian Husband—in some American states and cities at least—but I still live in an unorthodox manner, and am part of what might be one of the last American generations to experience queerness as a profound outsiderhood, a coming-of-age that will always form me, no matter how social worlds change. But that times are changing matters here, in that I’d like to see those of us who have lived outside of what has been the American norm to have an influence on what American form is, and will become. I’d like all of us to better embrace Americanness itself as a hybrid, multiple identity and resist singular ways of defining ourselves. That’s the fluid, “queerish” part of the equation.

As for genre, I understand my work to reside in the space between memoir, long-form essay, and poetry. I started writing as a poet and in many ways I still think like a poet, in terms of sound, breath, white space, and image-based structure. The gift and the risk of hybrid nonfiction form is its potential for breadth and complexity. At the same time, invented form is unfamiliar form. Unfamiliar forms scare readers who prefer the comfort of disappearing into the apparent real of linear narrative over the more active style of navigating forms that mimic the confusing palimpsest of actuality.

So where does this form sit? I don’t know. Wherever she damn pleases? In the bookstore that seat might be with the memoirs or essays but also might be on the LGBTQ and Feminist Studies shelf. I consider myself more essayist than memoirist in that subject tends to come before story in my process, but I’m OK with the memoir tag, especially if that descriptor invites more readers to brave an unfamiliar narrative structure.

AY: I’ve been wondering about the possibilities of shifting point-of-view in writing about the self. In Body Geographic, I noticed that you created a 19th-century version of yourself arriving in Chicago for the World’s Fair. You wrote in third person about this “self,” as a way of describing one side of your own character. What did this help achieve that couldn’t be accomplished in the typical first-person voice of memoir writing?

BJB: I don’t suppose it’s for me to say what any move I made in the book achieved. I can only speak to what I wanted in the moment of making, which was, in the case of creating that 19th century woman fairgoer, another way to inhabit history in a woman’s body. I wanted a counter to the bland interior of the statuesque symbol of Columbia. I wanted the desiring woman to reach out from the past and include me. I wanted to be a part of what I connect to so strongly in the literary version of that 19th century woman, such as that of Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, who comes to the city to change herself. I love studying the history of places, and in particular cities. Reading about what was here before brings me great intellectual and imaginative pleasure. Moments in the book such as the one you describe are my way of attempting to create embodied history.

JS: I find Body Geographic to be a fascinating, therapeutic (in my case), and very complex book. Its “insets” are marvelous for magnifying the people and events that dominate portions of your characters’ lives and so shape your characters’ identities. As I struggle to organize my own collection of essays, I would like to know how you kept track of the characters, events, images, and themes that occur and recur throughout Body Geographic. Did you lay them out in some visual way (as I am trying to do with Post-It notes on a white wall) to check for balance, forward movement, repetition? Did you diagram the book? Did you try any strategies that didn’t work?

BJB: I’m extremely intentional about the symphonic echoes and visual image design balances of all my books, but with Body Geographic—this is my third book— after many years into writing, I was able to see and hear the whole thing well enough to work without much of a visual map. I used to need a great deal by way of visual form props; in previous books I’ve made charts, graphs, color-coded tables of contents. I made what I called form wheels where I used something like post-its to do exactly what you say—track visual balance, repetition, echoes, and so forth. But with this book I found I was able to keep more of the design in my head.

Mostly what I did this time was keep these echoes in mind as I listened for where I needed return, repeat, and balance. I did keep the table of contents hanging on walls and bulletin boards wherever I worked, which functioned as my diagram, but I was never wed to this plan. I changed the order and chapter focus more times than I can remember. The details and echoes came to the page this time by ear and memory and intuition, and with occasional guidance from draft readers who noted I’d lost hold of a thread. Also, I cut quite a bit of over-repetition in later drafts.

What I’ll say in general about form-mapping activities is that they often work for awhile and then stop working, seemingly mysteriously. We may just outgrow them as we move toward finishing a book. My best advice is that the writer should devise the best way of working for her/his way of thinking and imagining, but never hesitate to abandon a process that’s stopped working. As writers, we have to be as creative and flexible about our processes as we are about the form of the work itself.

LA: As you tell your story, you skillfully weave the theme of water throughout–from the three tiers of spouting water at Buckingham Fountain; to Helen Keller’s bodily encounter with water and her thrill of connecting it to its name; to asking the reader to imagine what it would be like if their own city flooded. You write: “Water pulls the body forward. Water hems the body in. Nothing feeds longing like uncertainty, and nothing is more uncertain than a horizon line where the wide haze of water swallows the hard border of sky.” This made me especially curious about the question you posed in the caption for the illustrated map, Mississippi River Meander: “For don’t we all live on waterfront property?” Could you offer your answer to this question and/or elaborate on this theme?

BJB: I was attracted to that map of the many shores of the Mississippi—so deeply attracted that I have a version of that map tattooed onto my right arm—because the image looks to me like human life. Our shorelines shift. Change reroutes us. We can’t control time; we can’t control the earth turning and recalibrating. I started writing this book thinking I’d be able to pin down my understandings of identity, ethnicity, and the meaning of place but instead I found out there is no fixed meaning beyond this: places, our bodies, the borders of things just keep changing.

—

Barrie Jean Borich is the author of My Lesbian Husband, winner of the American Library Association Stonewall Book Award. Her new book, Body Geographic was published in the American Lives Series of the University of Nebraska Press. She’s the recipient of the 2010 Florida Review Editor’s Prize in the Essay and the 2010 Crab Orchard Review Literary Nonfiction Prize, and her work has been named Notable in Best American Essays and Best American Non-Required Reading. She was the first nonfiction editor of the Water~Stone Review and a longtime faculty member in The Creative Writing Programs at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota. She is currently a member of the creative writing faculty of the English Department and the MA in Writing and Publishing program at Chicago’s DePaul University and splits her time between Minneapolis and Chicago.